Harness Data to Understand Gender-Specific Barriers to Financial Inclusion

Suggested Approaches

- Don’t just collect data; use it as empirical evidence for policy, regulatory, private-sector, and consumer benefits.

- The collection of data should be grounded in policy objectives to determine what is collected (for example, a mix of qualitative and quantitative data), when it is collected (baseline, frequency), and where it is collected (primary and secondary sources).

- Sequence data-collection efforts and use emerging technology to support the analysis to reduce the resourcing burden. Ensure that data is collected, transmitted, and analyzed while maintaining data-protection and privacy principles.

- Where possible, anonymized data should be made public to allow private-sector actors to harness and develop business models that support policy objectives, including competition and inclusion.

Timely, appropriate, and reliable data can contribute to policies and regulations for DFS that effectively balance financial-sector development objectives. Historically, policy makers have relied on data collected from financial institutions (supply-side data) to achieve stability and integrity outcomes. An added focus on access, usage, and quality of financial services (demand-side data) emerged around 2010, when many countries started developing national financial inclusion strategies (NFIS) (GBA 2015).

The persistent gender gap in financial inclusion is one of the primary concerns for policy makers and regulators as they build more inclusive financial sectors (AFI 2017). Understanding and addressing the gender gap is a complex, cross-cutting policy issue—one that warrants a robust theory of change, a stronger evidence base, and coordination between a diverse set of stakeholders within the economy.

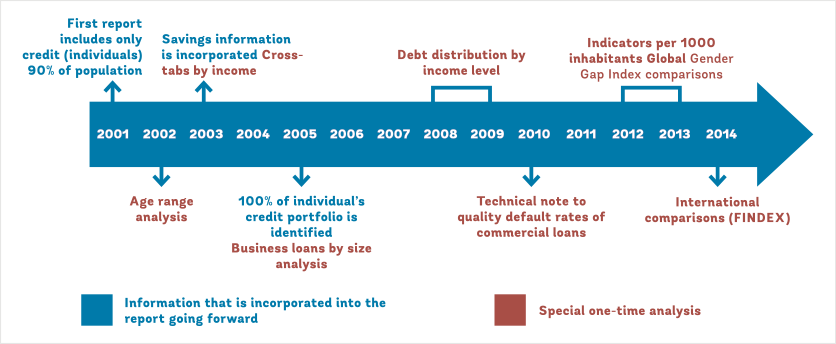

If collected and utilized effectively, sexdisaggregated data can provide insights into the financial lives and behaviors of different segments of the population. Such data can identify constraints and drivers across social, cultural, economic, and financial-sector contexts. Significant innovations in the world of big data have enabled the gathering and processing of larger volumes of data at greater velocities (or more frequent intervals). As a result, there is more potential for timely and actionable data that can drive policy and private-sector business models alike.

Country Examples

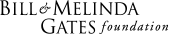

From 2000 to 2010, Chile developed and implemented its second five-year Equal Opportunity Plan to ensure the inclusion of a gender perspective in public policy. During this period, ministries established annual gender goals, which were then rolled into annual commitments. Sex-disaggregated data was prioritized as a key element in the design and evaluation of public policies and legislative reforms, as well as in the monitoring of annual gender goals. This energy also flowed through the financial sector. Chile became one of the world’s first countries to track sex-disaggregated data from its financial system consistently.

Progression of Variables Collected and Analysis Conducted, 2001 -2014

In 2010, Malaysia’s central bank, Bank Negara Malaysia, committed itself and the country’s financial sector to collecting sex-disaggregated data. The bank’s objective was to understand the financial inclusion gender gap and develop more inclusive policies and regulations. It collected supply-side data from regulated institutions and complemented it with demand-side data through a demand-side financial inclusion survey conducted every three years.

In 2023, Bank Negara Malaysia proposed a financial inclusion framework for 2023–26 that integrates gender-equality considerations as a cross-cutting theme. The framework builds on the focus on sex-disaggregated data and recognizes specific challenges and interventions, such as gender-smart products and financial education for subgroups within gender (such as youth, low-income, SMEs).

A nationwide effort across stakeholders may not always be possible, however. In such cases, there is still significant scope for financial-sector policy makers and regulators to spearhead the focus on sex-disaggregated data within the financial system and build broader awareness and commitment.

For DFS providers, sex-disaggregated data can contribute to a more gender-intelligent design of their business models, tapping into the needs of a large section of the population. Institutional data such as diversity of the workforce and women in leadership positions can create the impetus for increasing capacity to implement a more potent business model.

Market data can help better segment the market to build awareness, convert more women into customers, remove inherent bias (for example, in credit algorithms), and examine feedback or complaints from existing women customers. Utilizing sex-disaggregated data can contribute to growth in customers, revenue, and margins, ultimately benefiting the provider while also providing innumerable benefits to the consumer. Figure 4 highlights some of the benefits of sex-disaggregated data for key stakeholders.

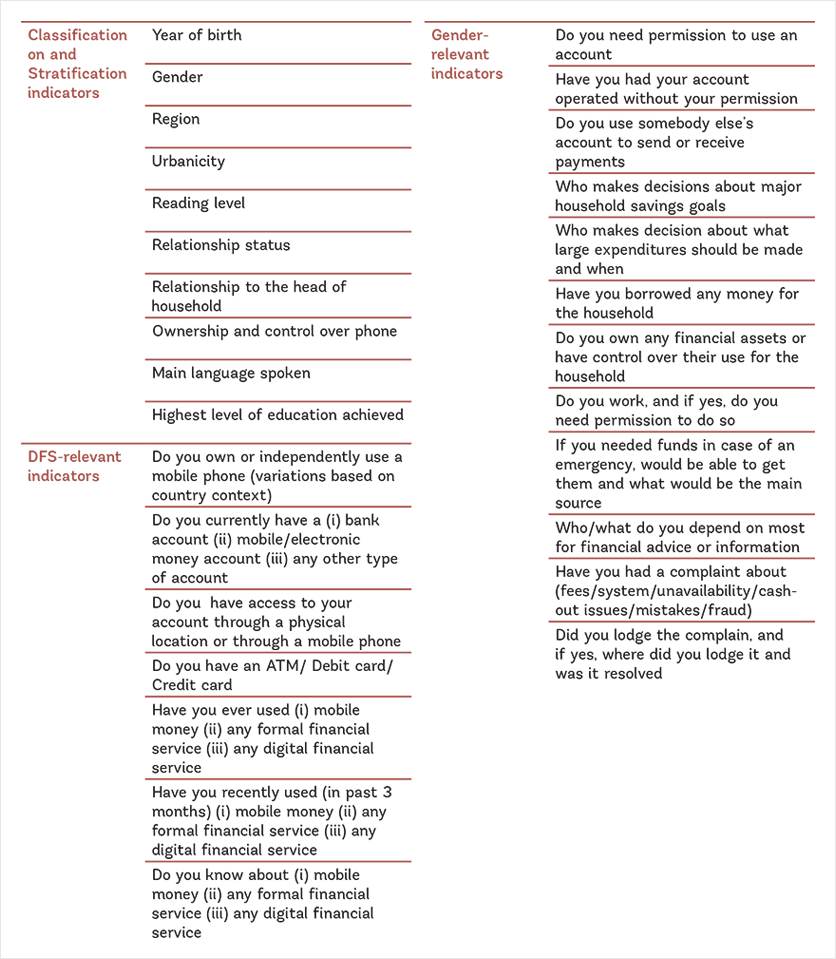

Types of Sex-Disaggregated Data

A good stock of both supply-and demand-side data is a useful source of information for both policy makers and other interested stakeholders. Supply-side data highlights trends in the types of financial services being provided and data on its uptake, while demand-side data provides insights into how financial services and supporting infrastructure are being accessed or perceived. Figure 5 and Figure 6 provide potential data variables that could be part of a sex-disaggregated dataset for policies and regulations for DFS.

Demand-Side Data

Demand-side data is often organized into categories that help explain current and potential interactions with the financial sector through questions about awareness, perceptions, and behaviors in the context of financial services. Additional questions are often administered to provide insights into social, cultural, and economic factors that affect financial-sector interactions. The variables in Figure 5 focus on questions that are specific to DFS and gender, as developed within demand-side survey methodologies and NFIS.

Benefits of Sex-Disaggregated Data

World Bank

Sample Demand-Side Data Questionnaire

World Bank

Selected Resources for Policy Makers: Demand-Side Survey Methodologies

Global Findex Database: The World Bank’s Global Findex database is a source of data on global access to financial services from payments to savings and borrowing. Indicators on access to and use of formal and informal financial services and digital payments are updated every three years.

Financial Inclusion Insights: Financial Inclusion Insights was a research program funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to build a meaningful knowledge base on how the financial landscape is changing across eight countries in Africa and Asia.

Gender and Information Communication Technology Toolkit: Developed by the US Agency for International Development, this toolkit contains a brief, easy-to-use guide to facilitate survey preparation, data collection, and data analysis, as well as a suite of quantitative and qualitative survey tools to obtain data on women’s access and usage of mobile phones and other connected devices.

Various countries have contextualized and adapted the methodologies above to create national demand-side surveys. Many countries have collected national demand-side data in the context of developing NFIS to serve as a baseline, to set targets, and to measure progress.

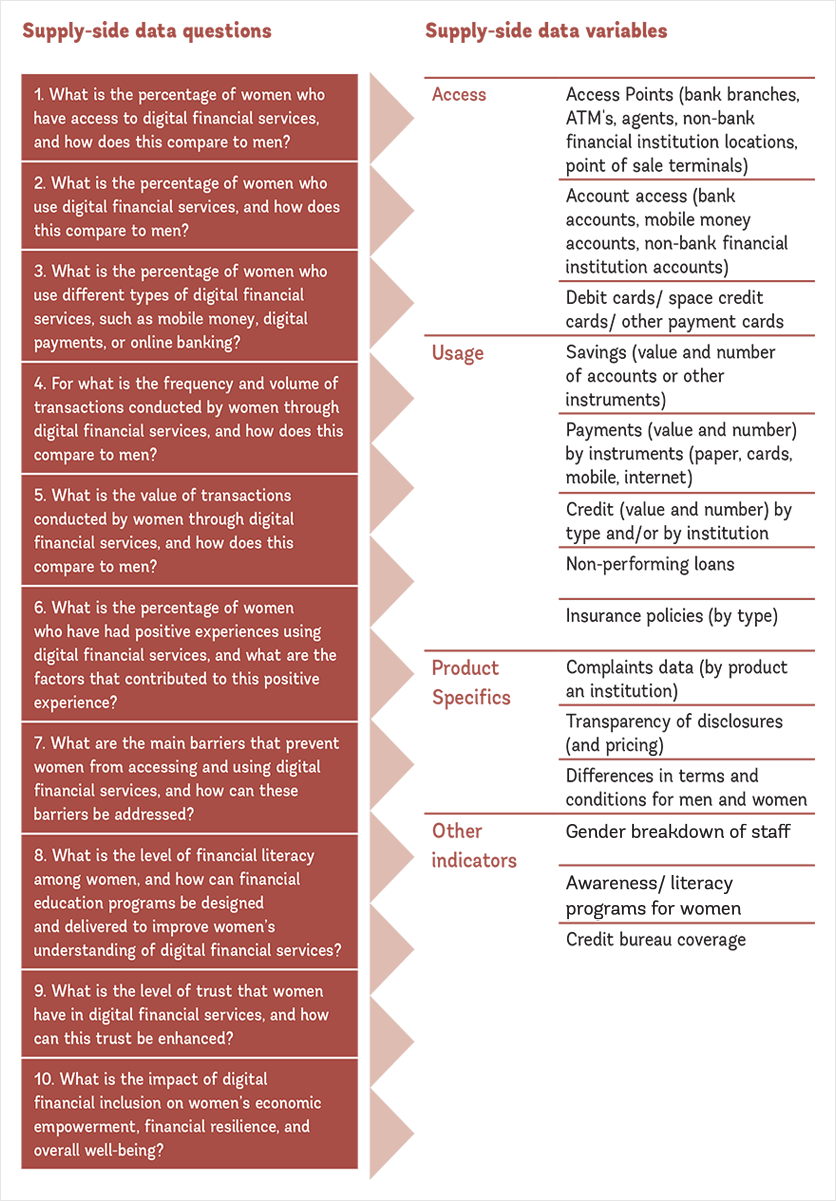

Supply-Side Data

Supply-side data is organized into three categories: access, usage, and product specifics. Further granularity arises implicitly from data collection from different types of providers. For example, if the gender gap in account ownership differs significantly between banks and nonbank providers, this could provide insights into resolving constraints to access. Further investigations may be necessary for other, more complex indicators. For example, if the number of complaints from women is higher at digital banks than at conventional banks, this may signal more engagement and interaction with digital banks, rather than a simple difference in quality of service.

The figure presents potential indicators for supply-side data. These include (i) gender-relevant indicators and sex-disaggregated indicators collected by the International Monetary Fund’s Financial Access Survey and (ii) additional gender-specific indicators collected by policy makers at the country level.8 Please note that this is not an exhaustive list.

Potential Questions and Variables for Supply-Side Dataset

Alliance for Financial Inclusion

A growing number of regulators are collecting supply-side data from regulated institutions. For example, 82 countries collected and reported sex-disaggregated data to the Financial Access Survey in 2022. Similarly, the Alliance for Financial Inclusion (AFI) has begun collecting disaggregated indicators from member institutions in the AFI Data Portal. As of August 2020, a total of 14 AFI members were collecting sex-disaggregated data on the supply side (AFI 2020).

Policy makers could consider doing an assessment of ongoing data-collection and management practices among FSPs to supplement and guide the supply-side data-gathering process. Appendix A includes a sample questionnaire designed for financial-sector policy makers to assess and understand the data-collection, storage, and management practices and capacity of financial institutions under their regulatory ambit, especially with respect to sex-disaggregated data.

Firm-Level Data

The data in figures 5 and 6 focuses on sex-disaggregated data for individuals. Interest is also growing in collecting data about women-owned or women-led SMEs to inform policies and programs to foster more inclusive economic participation. Such data includes instances and usage of business accounts, transactions and cash management, trade products used, and collateral registries of movable and immovable assets. Collecting this information is challenging. It would require financial institutions to track the gender of business owners-something that few banks currently do. In addition, collecting this information does not necessarily lie within the legal mandate of a regulator and can introduce bias into decision-making.

Country Examples

Building on an initial baseline survey from 2006, the Central Bank of Kenya has worked with partners to carry out an annual demand-side survey on information relevant to financial inclusion. Much of the data collected is sex disaggregated and shows the extent to which men and women differ in access, usage, and some aspects of financial literacy. The data has helped the Central Bank and other stakeholders monitor progress toward Kenya’s development and financial inclusion goals and informed the bank’s input to regulatory regimes for microcredit institutions and mobile money and other payment service providers. Importantly, it has also helped the Central Bank of Kenya support simplified due diligence requirements. The survey has recently been enhanced to provide additional data on usage and quality, considering the significant increase in access to the gateway services, such as mobile money, since the survey began.

The full survey methodology and the questionnaire are available at https://www. fsdkenya.org/category/finaccess/finaccess-household-surveys/finaccess-2021/

The Central Bank of Egypt has adopted the promotion and coordination of a gender-inclusive financial system as one of its priorities. Its first step was to initiate a process to collect sex-disaggregated supply-side data. The central bank started to formulate a strategy for doing so in early 2018. The aim was to create a baseline for tracking progress toward financial inclusion goals and establish an evidence base for more timely and targeted policy interventions. The bank has become the first regulator in the Middle East and North Africa Region to have sex-disaggregated data

On the national level, the government has made gender equality and women’s empowerment a priority through its sustainable development strategy “Egypt Vision 2030,” which addresses gender equality and women’s empowerment under each of its pillars. The Central Bank of Egypt has signed a memorandum of understanding with the National Council for Women in which it committed to cooperate on the following:

- Setting clear targets for Women’s financial inclusion as part of the Women 2030 strategy

- Increasing women’s access to formal financial services through competitive and quality DFS

- Removing impediments in legal and regulatory frameworks to promote women’s financial inclusion

- Identifying rural women facilitators and building their capacity to raise awareness of financial education

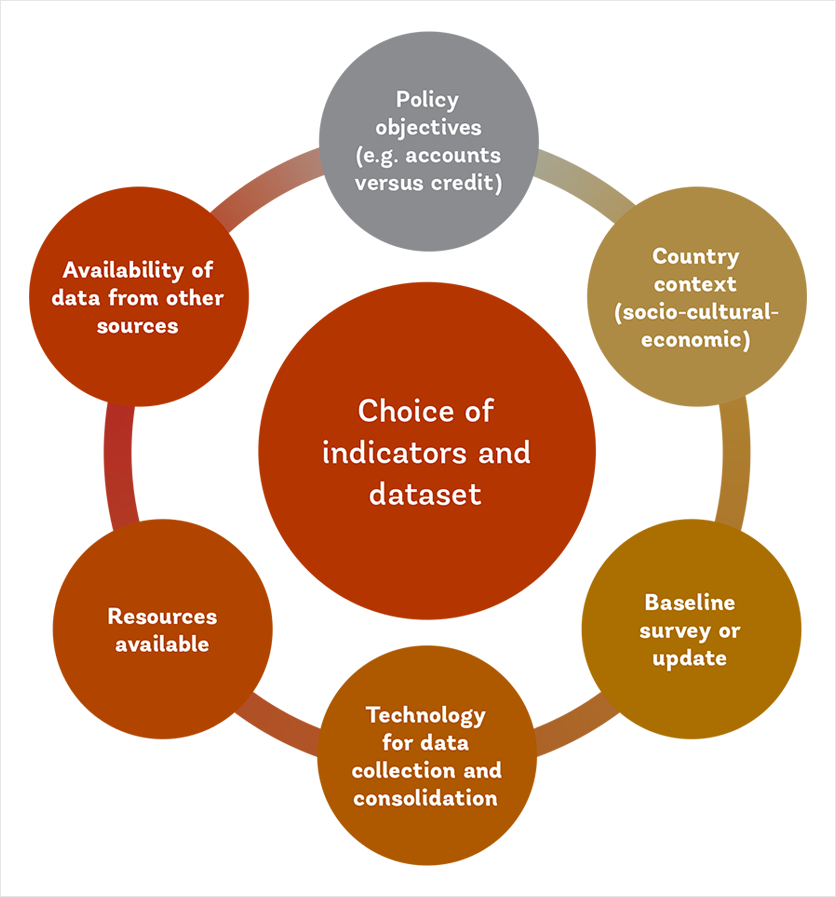

Choosing Indicators and the Dataset

With emerging trends in data science, there has been an exponential increase in how data is collected, how often it is collected, and what can be done with it. Policy makers and regulators need to analyze the benefits of having timely, accurate, and good-quality data against objectives, costs, and capacity constraints. Figure 7 highlights the considerations for selecting and prioritizing demand-and supply-side indicators.

Resource for FSPs: Using Digital Solutions to Address Barriers to Female Entrepreneurship

This toolkit developed, by the World Bank, practical guidance to help teams working on women’s entrepreneurship projects apply digital solutions to project design and policy advice. The toolkit includes a DIAGNOSTIC METHOD, applied at the country level, based on some standardized and automated indicators, with a supporting analysis guide and a multi-method analysis tool to interpreting the data.

Choosing Indicators

World Bank

Data-Collection Methods

It is important for policy makers to work collaboratively with financial institutions to collect sex-disaggregated data in ways that fulfill the need for more and quality data that can inform policy without placing an undue compliance burden on financial institutions.9

To be able to do this, policy makers must build awareness within regulatory and policy-making institutions, as well as in the private sector, about potential benefits for customer data segregated by gender while also cautioning about the risks.

Sex-disaggregated data can be collected in several ways, including the following:

1. Consumer surveys and questionnaires: Surveys and questionnaires can be used to collect both quantitative and qualitative sex-disaggregated data on financial services. These can be administered online, by phone, or in person and can include questions about the use of financial services, access to financial services, and barriers to accessing financial services.

2. Focus groups: Focus groups can be used to gather qualitative data on women and men’s experiences with financial services. These groups can be composed of individuals who are representative of the target population and can provide valuable insights into the specific challenges and needs of women and men in accessing financial services.

3. Data from FSPs: As mentioned above, FSPs are a rich and imperative source of sex-disaggregated data. Policy makers can require providers to report data on the number of women and men who use their services, as well as information on the types of services used and the amount of money invested or borrowed.

4. Administrative data: Government agencies and other organizations may have administrative data that can be mined for sex-disaggregated insights on financial behavior. This can include data on income, education, and employment, which can be used to understand the factors that influence access to financial services.

Resource for FSPs: The Gender Data Playbook for Women’s Financial Inclusion

The Gender Data Playbook of the Women’s Financial Inclusion Partnership offers a step-by-step guide for policy makers to improve the collection of high-quality, supply-side, sex-disaggregated financial data to drive women’s financial inclusion.

5. Alternative data: As digital footprints grow through the use of mobile phones and other digital channels for services, these footprints and nontraditional sources of data may provide additional insights on behavioral patterns, including take-up and use of service as well as prominent gaps.

6. Use of e-services and other digital platforms: For example, if the use of government services through digital means has increased, it may offer insights into digital literacy and digital inclusion, particularly if there are gender-based disparities.

It’s important to note that to collect sex-disaggregated data effectively and interrogate it coherently, it is necessary to have a clear definition of sex and gender, as well as to ensure that data-collection instruments, such as surveys or questionnaires, are inclusive and respectful of diverse gender identities and recognize and mitigate risks that may arise. The application of data-analytics tools can then support the process of translating this data into actionable policy (WFID 2023).

Country Examples

In Chile, the Superintendence of Banks and Financial Institutions (Superintendencia de Bancos e Instituciones Financieras, SBIF) started with credit registry data, as every borrower has a gender-coded national ID number. Three years later, SBIF started requesting sex-disaggregated savings data directly from financial institutions, having worked with them to ensure their ability to collect and report this data.

The Central Bank of Egypt followed a similar approach. It engaged with financial institutions to understand their capacity to report sex-disaggregated data. After finding that only commercial banks and the Egypt National Postal Office used the 14-digit gender-coded national ID, the central bank required these institutions to report disaggregated first (rather than others) in the first iteration of their guidelines.

In Malaysia, financial institutions are required to submit customers’ unique ID numbers as data items to Bank Negara Malaysia. The central bank then cross-references against the national ID system to disaggregate, by gender, the various indicators it already collects.

Data is electronically submitted by FSPs and processed based on unique national ID numbers. After processing, Bank Negara Malaysia uses a business-intelligence tool to extract and analyze data. Providers in Uganda also submit surveys and regulatory reports online, rather than on paper.

Leveraging Technology for Collecting Supply-Side Data

Technological advances often support the collection and analysis of supply-side data. In Costa Rica, providers use the XML programming language to submit monthly data through a secure channel that directly connects to the General Superintendency of Financial Entities database. The superintendency uses the database to calculate indicators, while a Microsoft Excel data-mining tool produces customized, predefined reports.

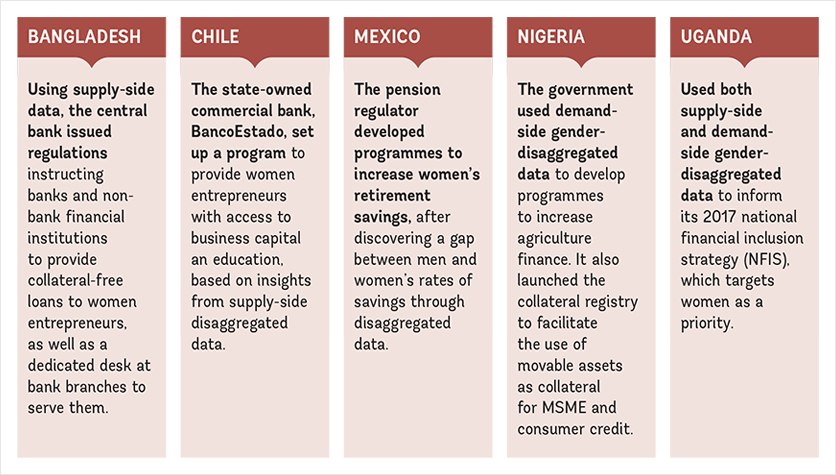

Use Cases of Sex-Disaggregated Data

Collecting sex-disaggregated data about who uses financial services—and what women need from financial products—can provide vital information. But data collection is a tool, not an end. Policy makers need to know how to use this data effectively to design and evaluate policies to increase women’s financial inclusion (UNSGSA, n.d.). Sex-disaggregated data can be used for policy design, impact evaluations, awareness building, and as a public good for financial-sector participants.

Findings on Data Use for Policy Makings

UNSGSA

- National financial inclusion strategies: Sex-disaggregated data has been used widely for NFIS or similar strategic approaches to DFS or fintech. First, sex-disaggregated data provides a much-needed baseline for analytical work leading up to NFIS development. Second, it helps develop appropriate headlines and intermediate targets for reform actions. Third, regular data collection then allows responsible entities to monitor progress and consider course corrections, allocate resources, or revise targets. Finally, timely data can support impact assessments and evaluations of completed NFIS.

- Regulation: Regulators have historically been the most active users of consolidated sex-disaggregated data. For example, several regulators have simplified KYC requirements based on constraints highlighted through sex-disaggregated data. Similarly, several regulators have implemented market-conduct and consumer-protection regulations that create more transparency (for example through key facts statements) and enhance grievance-redressal mechanisms. As more regulators are moving toward suptech solutions to support and enhance supervisory processes, we will see more advanced use cases and interpretation of data coming to the fore.

- Literacy and awareness campaigns: Broader financial literacy and awareness campaigns have utilized sex-disaggregated data in some cases to improve the content and delivery of messages. For these campaigns to have an impact, they need to be situated within an understanding of the behaviors and attitudes of women clients.

- Private-sector innovation: The private sector is often a supplier of sex-disaggregated data. Moreover, new entrants in the DFS landscape can benefit from supply-side and demand side data to build innovative solutions. For example, aggregate supply-side data may help identify opportunities to improve communication and delivery channels, while aggregate demand-side data may help business model assumptions around potential market sizing and segmentation.

Considerations and Challenges

Data collection and sharing may pose additional challenges, and authorities should pay special attention to the following considerations:

- Accuracy and timeliness: The responsibility for maintaining the accuracy and timeliness of data could create reputational risk for policy makers. For example, if demand-side surveys are not representative of population dynamics, or if supply-side data is reported with errors by an FSP, this would limit the usefulness of the data.

- Data protection and privacy: With extensive datasets that also contain identification details, there are additional challenges of complying with data-protection and privacy laws or standards. The overall process should incorporate “privacy by design” principles (i) to protect the data rights of existing and potential financial-sector users and (ii) to allow FSPs to meet their obligations as custodians of customer data.

- Misuse of data: Even when data is collected with informed consent and shared securely, there are risks when new and emerging technology is applied to analyze or process data. For example, since sex-disaggregated data is relatively new, systems and machines are likely to be trained with data that represents material gender gaps. Hence, the use of artificial intelligence and algorithms may exhibit biases and provide suboptimal decisions that do not benefit DFS providers or their potential customers. Europe’s approach to regulating for an equal artificial intelligence provides some insights into risks and regulatory mitigants (Allen QC and Masters 2020).

- Resourcing constraints and opportunity costs: The collection and consolidation of sex-disaggregated data entails intensive resource allocations, both in terms of staff and information systems. Publishing and utilizing the data adds further costs. Clear cost-benefit analyses in consultation with the private sector may help prioritize and sequence the overall process.