Developing and Enabling Policy Environment with Specific Focus on Gender-Related Aspects

Suggested Approaches

- Adopt tiered KYC regulations and a risk-based approach to customer due diligence to ease access to DFS for women consumers.

- Evaluate the possibilities for alternative credit-risk assessments to facilitate credit access for women consumers.

- Introduce a gender lens in consumer-protection regulations and processes.

- Build a gender-intelligent approach for vulnerability-risk management and market-conduct supervision.

- Carry out market monitoring to ensure nondiscriminatory lending.

- Build appropriate recourse mechanisms.

- Ensure ethical and transparent cost and fee structures.

- Adopt enabling agent banking regulations.

Source:Adapted from Bin-Humam, Izaguirre, and Hernandez (2018).

Gender-neutral policies do not always result in gender-equitable outcomes and can perpetuate existing gender inequalities (Buvinić and O’Donnell 2017; Hankivsky and Cormier 2011) and limit women’s financial inclusion. Gender-neutral policy may in fact be gender blind if it fails to acknowledge and address the social norms, discrimination, lack of collateral, and other barriers that affect women’s use of financial services. Understanding how regulations may inadvertently exclude vulnerable groups, including women, is crucial in creating gender-intelligent regulatory frameworks that enable women’s usage of DFS.

The following are key policy areas that can potentially aid in advancing women’s digital financial inclusion:

Tiered KYC regulations and a risk-based approach to customer due diligence

People with low incomes, especially women, often lack access to official ID documents. To ensure that women are able to access formal financial services, customer due diligence requirements must consider these constraints. By allowing simplified customer due diligence in lower-risk scenarios, as well as recognizing alternative forms of ID documents that women typically have, regulators can enable more women to enter the formal financial system.

Tiered KYC regulation is a risk-based approach to customer due diligence in the financial industry. It involves assigning different levels of scrutiny and verification requirements based on the perceived risk of a particular customer or transaction (World Bank 2018). Under a tiered KYC approach, customers are assigned to different tiers based on their risk profile. Generally, the higher the perceived risk, the higher the tier and the more extensive the KYC requirements.

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) has adopted a risk-based approach to customer due diligence as the most effective way to combat anti-money laundering/combating the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT). FATF guidelines on tiered KYC are intended to minimize barriers to the use of financial services by underserved communities, allowing for simplified customer due diligence to be used in lower-risk scenarios.

Resources for policy makers: Regulatory approaches to risk-based customer due diligence

CGAPs’ technical note on risk-based customer due diligence outlines the main risk-based approaches to CDD, provides examples from regulatory systems across the globe, and weighs the pros and cons of each approach.

The tiers are typically classified as shown in table 1. However, it should be noted that tiers are defined by each jurisdiction based on its risk appetite and often take the form of a limit on transactions and/or a minimum daily balance to be maintained in the bank account.

Table 1: A Sample of KYC Tiers According to Customer Profiles

| Tier | Customer Type | Authentication/ Verification | Types of Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tier 1 | Low-risk customers, such as individuals opting for a basic bank account; may have a good credit history and established relationships with the financial institution. | Basic customer information (name, gender, date of birth, address, photograph). | Small-value transactions and basic deposit accounts (for example, prepaid low-value products or basic accounts with strict deposit/ withdrawal thresholds). |

| Tier 2 | Medium-risk customers, such as small businesses or individuals with more complex financial needs. | Higher ceilings and requirements but less than full customer due diligence. Government-issued ID (that is, passport or driving permit), SIM registration, driving permit. | Medium-value accounts. Higher transaction limits allowed, and higher balance to be maintained in the account. |

| Tier 3 | High-risk customers, such as politically exposed persons or customers involved in high-value transactions. | Government-issued ID, biometrics to be verified against government databases, and verification of source of funds, as well as ongoing monitoring of transactions. | High-value accounts, larger loan sizes as defined by the regulation. This includes special accounts for businesses (for example, agents and merchants) with much higher ceilings than individual accounts. |

Adapted using the most common themes from guidelines by various authorities.

Country Examples

The Unique ID Code for Mexican Citizens (Clave Única de Registro Nacional de Población, CURP) is a key uniquely associated to each individual in the country, including noncitizens. It is issued by the National Population Registry. Birth certificates and the CURP serve as foundational IDs that enable individuals to obtain functional IDs that are used to vote and to access social security programs and public health care services.

However, low-income individuals may lack the standard documents to satisfy KYC and AML/CFT requirements to open an account or obtain a loan. In order to address this concern, risk-tiered accounts were created in 2009 with related tiered customer due diligence requirements. Additionally, in 2017, regulatory adjustments to the identification process were introduced. These included requiring financial institutions to collect and verify biometrics for opening higher-risk accounts, obtaining loans, or performing high-value transactions at bank branches. These regulatory adjustments help to increase access based on the risk of transaction, and they also reduce identity theft and further mitigate fraud.

GPFI (2018).

Omission from the regulatory framework of such a tiered approach may unintentionally exclude large segments of society from the financial system—including women in poorer segments of the population who are less likely to have the documentation needed to access financial services.

In addition to tiered KYC, authorities can also explore remote KYC (or e-KYC) to expand financial inclusion to new women customers who cannot easily visit agent locations or branches of financial institutions.

Remote KYC (e-KYC) and onboarding refers to the process of verifying the identity of customers and setting up their accounts remotely, without requiring them to visit a branch or office in person. This process typically involves using digital technologies, such as video calls, biometric authentication, and electronic signatures, to verify each customer’s identity and complete the onboarding process.

Introducing a gender lens in consumer-protection regulations and processes

Strengthening the regulation of financial consumer protection is paramount in addressing the needs of vulnerable groups. Protecting and educating users of financial services, particularly the vulnerable and the poor, are two of the most important elements of financial inclusion. Women represent the largest segment of the poor, tend to be the least educated, and are therefore most at risk to falling victim to abusive business practices and illegitimate providers.

While individual financial institutions have a responsibility to educate consumers about their products, policy makers and other government officials also have a crucial role to play in ensuring that women have sufficient knowledge and skills to feel empowered about their financial decisions and to make choices based on a broad understanding of how financial products work, rather than on knowledge driven by a particular product.

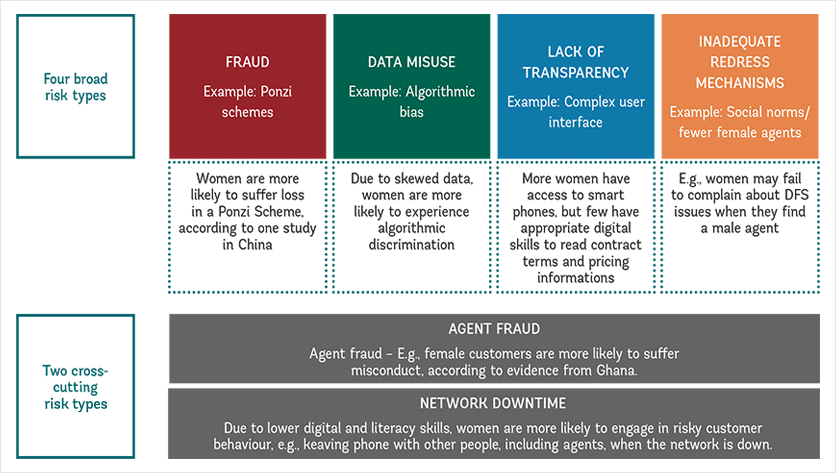

Women Are More Susceptible to DFS Risks Than Men

Research has found that women are often less familiar with financial services and digital technologies than men. Moreover, women tend to have lower digital and financial literacy than men, which makes women more susceptible to DFS risks. Emerging evidence highlights that women and other vulnerable groups are more likely to fall victim to various types of cybercrimes (Chalwe-Mulenga, Bin-Humam, and Duflos 2022), including the following:

- Phishing: When a hacker pretends to be an institution in order to get users to divulge personal data, such as usernames or passwords, via email or social networks.

- Pharming: When a virus redirects users to a fake page, causing them to divulge personal information.

- Spyware: When malicious software penetrates a user’s PC or mobile phone and extracts personal data.

- SIM card swap: When someone poses as the user and obtains private data by gaining access to the SIM card.

What Policy Makers Can Do to Ensure That Vulnerable Customers, Including Women, Are Protecteted

By employing gender-intelligent consumer protection, financial regulators and policy makers can ensure that women have equitable access to financial services and are protected from discriminatory practices in the financial sector. Accomplishing this involves the following actions:

Building a gender-intelligent approach for vulnerability risk management and market-conduct supervision

Vulnerable populations, including women, are more susceptible to financial vulnerability due to factors such as lower incomes and limited credit histories. It is crucial to provide enhanced support and protection to these individuals to prevent their circumstances from being worsened by their engagement with the financial sector. Considering that vulnerable populations face heightened risks as financial consumers, it is important for financial-sector regulators and supervisors to adopt a vulnerability lens when conducting market-conduct supervision. This approach enables the identification of any negative impact on vulnerable populations, with a particular focus on women.

DFS Risks Faced by Women Consumers

To build a vulnerability-based market-conduct supervision approach, financial authorities should undertake the following steps:

Step 1: Financial-sector authorities define vulnerability in the context of the sector. Vulnerability can be defined as a situation where consumers are at risk of being harmed or exploited by financial institutions due to various factors, such as their personal circumstances, lack of knowledge, or access to information.

Step 2: Financial authorities should identify which groups of consumers are most vulnerable to harm and disadvantage. This may involve conducting research or analyzing data to identify vulnerable groups based on factors such as age, income, education, or health status. It may also require specific efforts to improve access to reliable data. (For a non-exhaustive list of suggested indicators, please refer to table 2).

Step 3: Financial authorities should adopt a risk-based approach to market-conduct supervision that prioritizes the protection of vulnerable consumers. This may involve assessing the risk of harm to vulnerable consumers when developing policies and procedures and allocating resources accordingly.

Step 4: Financial authorities should develop guidelines and standards to set expectations for FSPs’ treatment of vulnerable consumers, including existing legal provisions within FCP regulation, especially in areas such as product design, marketing, customer service, and complaint handling. Since the topic is new, industry-dissemination initiatives may be necessary to ensure proper incorporation of the concepts.

Step 5: Financial authorities should work to improve consumer awareness of, and education about, existing financial products and services. This may involve providing educational materials and resources that are tailored to the needs of vulnerable consumers.

Step 6: Financial authorities should monitor providers’ compliance with guidelines and standards and take enforcement action where necessary. This may involve conducting inspections, investigations, and enforcement measures in cases of noncompliance.

Table 2: List of Variables That Contribute to a Consumer Profile

Various factors including socio-demographic: characteristics. Fomamcoa; capability, and life events or experiences can contribute to consumer vulnerability. The following is a non-exhaustive list of variables that can be used by financial authorities to build a framework for assessing consumer vulnerability.

| Sociodemographic Variables | Financial Capability Variables | Situational Variables | Types of Products |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Adapted from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10603-023-09535-w

CFPB’s Financial Skill Measuring guide: https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/bcfp_financial-well-being_measuring-financial-skill_guide.pdf

The “Guidance for Firms on the Fair Treatment of Vulnerable Customers” from the United Kingdom’s Financial Conduct Authority is meant to provide guidance to financial-sector firms on how to do the following:

- Understand the needs of their target market/customer base.

- Build staff capacity to identify and respond to consumer vulnerability and ensure that staff have the right skills and capabilities to recognize and respond to the needs of vulnerable customers.

- Respond to customer needs through product design, flexible customer service, and communications.

- Monitor and assess whether they are meeting and responding to the needs of customers with characteristics of vulnerability.

- Make improvements where this is not happening.

Monitoring markets to ensure nondiscriminatory lending practices

While establishing regulations prohibiting unfair lending practices is the first step, policy makers and authorities also need (1) to monitor lending practices to ensure that they are nondiscriminatory and (2) to enforce laws and regulations that prohibit gender-based discrimination in lending. This can include regular audits of lending portfolios, complaint mechanisms for borrowers, and penalties for institutions that engage in discriminatory practices.

Building appropriate recourse systems

Fair and transparent financial services include the ability for women and other vulnerable customers to seek redress when things go wrong. Well-designed recourse mechanisms can empower women, enabling them to take control of their finances and participate more confidently in the financial system.

However, it is important to ensure that unintended consequences are limited. In accessing remediation mechanisms, women may face barriers, including socioeconomic and cultural hurdles (such as a fear of backlash and a lack of knowledge about official procedures and available assistance) and procedural bottlenecks (including a lack of antidiscrimination legislation or gender bias). To ease these obstructions, regulators should mandate that providers develop tiered, appropriate, and gender-sensitive mechanisms to redress grievances—starting by conducting a gender analysis of existing grievance-redressal mechanisms.

Gender-sensitive Grievance Redressal Mechanism Checklist

- Is the institution’s grievance redressal mechanism accessible to women customers? If not, what barriers may exist?

- Is the institution ensuring that the grievance redressal mechanisms are visible to all customer segments, including women and other marginalized groups, considering potential literacy limitations?

- Is the institution’s grievance redress mechanisms confidential? How is the privacy of the complainant protected?

- Are staff members who handle complaints trained on gender sensitivity and how to handle gender-based complaints?

- Is there a gender breakdown of the types of complaints that the institution receives?

- Are there any gender biases or assumptions that may be present in the way that complaints are handled or resolved?

- Is there a monitoring process in place to ensure that access to and remediation outcomes of the grievance mechanism are provided on an equal basis?

Ensuring ethical and transparent fee and cost structures

Women tend to be more sensitive to cost structures surrounding financial products than men and are also less likely to find workarounds to avoid them. Research from emerging economies suggests that women have concerns around opaque and complicated cost structures for DFS transactions. In Kenya and Côte d’Ivoire, men were aware of ways to reduce transaction fees, while most women surveyed were unaware of such tactics (Smertnik and Bailur 2020). Regulators and policy makers have a role to play in ensuring that financial institutions disclose pricing information to vulnerable customers in a clear and understandable manner.

The European Union (EU) introduced the Gender Directive in 2012, which prohibits insurance companies from charging different premiums or offering different benefits on the basis of gender. This applies to all insurance products, including car, health, and life insurance.

Assessing Pricing Practices in Your Jurisdiction: A Checklist for Regulators

- What financial products and services are available to women consumers in your market? What financial products and services are used by women most frequently?

- What are the pricing structures for these products and services?

- Are any gender-specific products or services marketed to women customers (for example, health insurance or savings products specifically for women)? If so, are they priced differently than similar products or services marketed to men?

- Do any restrictions or eligibility criteria disproportionately affect women customers, such as minimum balance requirements or credit score thresholds?

- Do men and women who are extended credit offers receive the same average loan amount and interest rate while controlling for relevant variables?

- Have there been any reports of discriminatory pricing practices affecting women customers in your market (such as collateral requirements)? If so, what actions have been taken to address these concerns?

- Are any policies or regulations in place that prohibit discriminatory pricing practices based on gender? If so, are financial institutions in compliance with these policies and regulations?

Designing Women-Friendly Pricing Disclosure Documents: A Checklist for FSPs

To ensure that women consumers, often challenged by limited literacy, fully understand the pricing structure of products offered to them, pricing disclosure documents should include the following:

- A clear and concise summary of the institution’s commitment to fair pricing and nondiscriminatory practices, including a statement of its policies regarding gender-based pricing and any actions taken to ensure compliance with regulatory requirements.

- A breakdown of all fees and charges associated with the product or service, including interest rates, account fees, late payment fees, and other charges.

- An explanation of any discounts or rebates that may be available to women customers, such as reduced interest rates for loans or waived account fees.

- Information about any restrictions or eligibility criteria that may apply to women customers, such as minimum balance requirements or credit score thresholds.

- A comparison of pricing with similar products or services offered by other financial institutions, to help women customers make informed decisions.

- A clear explanation of the consequences of nonpayment or default on a loan or credit product, including any potential impact on credit score and other financial obligations.

- Visual aids, such as graphs, charts, or tables, to help women customers easily compare pricing and understand the terms and conditions of the financial product or service.

Source:Adapted from Federal Reserve System (2011), State Bank of Pakistan (2016), and Chien (2012).

Adopting enabling agent banking regulations

For women, combining technology with the human touch is critical. Given the lower digital literacy of women, they often rely on agents to transact, at least at the outset of their DFS journey. This was demonstrated in Kenya and Côte d’Ivoire, where women vocalized the importance of agents in their trust and confidence in DFS (Bailur 2020). Given the access and movement challenges that women often face, agents, both roaming and locally based, are essential for women to use financial services regularly.

The following are key considerations for policy makers while developing regulatory frameworks for agents:

Assessing the needs of women consumers is crucial. For example, in some contexts, gender parity in agent networks can further enhance women’s access and usage of a World Bank study in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Senegal found that DFS customers preferred agents of their own gender. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, women customers were 7.5 percentage points more likely to transact with women and to transact higher-value amounts. However, these results are not universal: in Kenya and Nigeria, Women’s World Banking research found that urban women had no preference for their agent’s gender (Women’s World Banking 2023). This research highlights the diversity of women’s wants and needs around DFS, and the importance of understanding how women consumers behave and designing policy accordingly. Where customers prefer women agents, the following points should be noted:

Better representation of women agents may increase the comfort and accessibility of DFS for women (Reitzug et al. 2020). Furthermore, when agents are located in women’s own communities, the time and cost required to travel to make financial transactions is reduced, lessening movement constraints and helping women improve their financial and digital literacy through hands-on support (Gray and Singh 2022).

Incorporate gender into agent rollout strategies, developing the business case for women agents in retail, noting the key capital and training constraints faced by the types of businesses that women operate in the national context—for example, hair salons and food stalls. When determining who is eligible to become an agent, governments should develop regulations that strike a balance between safety and inclusion.

Understanding both women’s expectations of agents, and agents expectations of the services they perform is crucial. Even with a variety of recourse mechanisms in place, agents often remain the first port of call for women customers. Understanding women’s expectations of agents in terms of the services and assistance they can extend is crucial while designing agent banking regulations. Are agents there merely to execute transactions, or, in the case of new customers, will they also be tasked with imparting basic financial literacy and consumer-safety information to the customers? Policy makers can invest in this research and then use the findings to encourage/incentivize agents who speak to women’s needs.

Trust in agents plays a large role in building women’s confidence in DFS. For many women, an electronic social payment will be their first interaction with DFS. When designed thoughtfully, cash-in, cash-out transactions can act as an on-ramp to DFS—women’s ability to access their money easily is crucial to women customers’ confidence with digital money. Trust in agents is particularly important in these nascent stages and should be noted in agent training.

Enabling alternative credit assessments and investing in credit infrastructure

Women face many barriers to accessing credit. The World Economic Forum suggests that 80 percent of women-owned businesses with credit needs are either unserved or underserved (Kende-Robb 2019). Lack of collateral, limited or non-existent credit histories, and gender biases all play a role in impeding women’s access to finance.

Women often lack immovable collateral, such as land or property, to act as security for a loan. Inheritance laws and social norms that discriminate against women owning property make it challenging to access normal credit, which can in turn limit women’s ability to invest in their businesses or improve their economic opportunities. Furthermore, property needs to be registered formally in order for it to be used as legal collateral, and this can involve complex and time-consuming legal and administrative processes. Women may face additional barriers while navigating these processes, particularly in countries where legal and administrative systems are less accessible or where women face discrimination in accessing legal services.

Another consequence of the gender gap in account ownership is that women’s lesser access to formal financial services limits their ability to build a credit history—which in turn makes it difficult for women to access secured credit, as lenders may be hesitant to lend to borrowers without a credit history. Furthermore, gender biases in credit scoring may favor male borrowers over women borrowers. For example, laws that require a husband’s consent before a wife can pledge collateral may limit women’s ability to access secured credit independently.

These challenges highlight the need for policy makers to consider nontraditional credit-assessment methods that circumvent collateral requirements to enable women’s access to financing.

Alternative data, such as mobile phone usage patterns or social media activity, can also be harnessed to build a credit score for women customers without credit histories or collateral—providing they have access to and are using a mobile phone. However, alignment on what constitutes alternative data and how it should be treated remains missing. Ensuring the availability and accuracy of the data collected is a challenge, further exacerbated by the absence of digitized public information about, and small digital footprint of, transactions by micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises. Regulators and policy makers can address this by issuing guidance on how alternative data may be sourced and processed-for example, by implementing the use of unique identifiers such as national IDs or other verified alternatives. Additionally, government agencies should also work toward digitizing their records and promoting the development and provision of access to open data systems (Chhabra and Sankaranarayanan 2019).

Types of Alternative Data Used in Credit History

- Mobile phone data has been increasingly used as an alternative data source for credit scores. This is because it provides insights into an individual’s financial behavior, such as their spending habits and bill payment history, which can be used to assess creditworthiness.

- Psychometric testing uses personality and behavioral tests to predict repayment likelihood and generate alternative credit scores among women (Khan 2018; Alibhai, Cassidy, Goldstein and Papineni 2022.). Some countries have used this approach successfully to extend credit to women and other underserved populations.

- Cash-flow-based lending uses a borrower’s cash flow and revenue projections to assess creditworthiness, rather than relying solely on collateral or credit scores. This approach has the potential to benefit women entrepreneurs, who may have less access to collateral and formal credit history.

- Group lending is a form of microfinance that provides small loans to groups of people, typically women, who are jointly responsible for repayment (Schuster 2015). Group lending can provide access to credit for women who may not qualify for individual loans because they lack collateral or a credit history.

- Social media data has also been explored as a potential alternative data source for credit scores. Some companies are using social media data to analyze an individual’s online behavior, such as their social connections, interests, and activities, to assess their creditworthiness. However, the use of social media data for credit scoring is still in its early stages and there are concerns about privacy and potential biases in the data.

Because women are also less likely to have fixed assets, collateral registries need to focus on movable assets. Establishing legal frameworks that allow assets such as machinery, inventories, receivables, agricultural goods, or animals to be used as collateral for loans will disproportionately affect women’s access to credit in a positive way.

Country Examples

The Bank of Ghana launched Africa’s first secured transactions registry in February 2010. The system enables borrowers to register both movable and immovable assets as security for credit given by lenders.

By registering assets in the Collateral Registry Application Software, the Collateral Registry minimizes information asymmetry between lenders and borrowers in credit transactions. According to a World Bank report, by 2016 the Collateral Registry had facilitated $12 billion in total financing for the commercial sector and $1.3 billion in loans to SMEs using just movable assets as collateral. SMEs received nearly three-quarters (73 percent) of all loans through the Collateral Registry as of December 2017, totaling $35 billion in finance guaranteed by movable assets. This registry signals real opportunity for women entrepreneurs, who make up 40 percent of all registrants and provide the SME sector with over $100 million in financing.

Encouraging private-sector participation

To foster innovative solutions and products that cater to the financial needs of women, authorities should encourage private-sector participation.

- Intensive and time-bound exercises such as hackathons/tech sprints can bring together innovators and FSPs to solve specific challenges in women’s financial inclusion. Organizing tech sprints focused on women’s digital financial inclusion can help bring together stakeholders from the private sector, government, and civil society to develop products and solutions suited for women consumers.

- Governments and development organizations can create certification programs that recognize organizations that have implemented gender-sensitive policies and practices, such as offering products and services tailored to women, providing equal opportunities for women to access financial services, using gender-intelligent design (GID), and promoting women’s leadership in financial organizations. Certifications can help incentivize private-sector organizations to invest in women’s financial inclusion and signal the organizations’ commitment to gender equality.

Country Examples

Swanari is short for Swanirbhar Naari, meaning “self-reliant lady” in Hindi. The Swanari tech sprint was an initiative aimed at promoting innovation and collaboration in the financial service sector in India. A partnership between the Reserve Bank of India Innovation Hub and AIR (Alliance for Innovative Regulation), the program invited fintech start-ups and other innovators to participate in challenges related to digital ID, payment systems, and regulatory compliance. The goal was to help women business owners, single women, and women with literacy challenges establish a digital financial footprint and increase their economic and financial resilience and well-being.

The program focuses on collaboration between regulators, innovators, and FSPs to create a sandbox environment that promotes the development of scalable and sustainable solutions.

The specific use cases included solutions for (a) improving digital and financial literacy for certain segments of women using behavior- led design, (b) helping women frequently save small amounts digitally, (c) enabling banks to use alternate credit data for women entrepreneurs seeking micro or small- business loans, and (d) leveraging technology to get more women recruited as business correspondents.