Overview

Policymakers and regulators who can spur innovation or adapt to innovation quickly are more likely to support DFS growth. Structured approaches may help balance policy objectives, facilitate market engagement, and provide a stronger basis for outcome measurement.

Innovation facilitators have become popular tools and approaches used by regulators to enable the development of DFS. The structure and design of innovation facilitators can vary greatly from simple points of contact within existing bodies to more structured framework environments to provide space for experimentation.

Generally, they focus on promoting greater knowledge exchange and interaction, with both new entrants and incumbents developing new technology-driven products and services. Facilitators can also be used to monitor market developments, including the challenges, risks, and opportunities related to technological innovation in the financial sector and the impact of this on financial stability.

Approaches

A number of regulatory tools and approaches have emerged in response to developments in the DFS landscape. The choice of regulatory tool or approach depends on policy priorities and ecosystem variables such as legal and regulatory frameworks, the complexity of the market, and the availability of resources.

- How well established is the legal and regulatory framework?

- What powers are afforded to the regulator by the mandate under which it operates?

- Is it a rules-based or principles-based regulatory framework?

- How competitive is the market?

- What is the state of financial inclusion (unserved or underserved individuals and MSMEs)?

- Number and types of financial institutions?

- How many regulators oversee financial supervision?

- What is the level of coordination with technology regulators?

- What is the level of development of the entrepreneurship ecosystem (incubators, accelerators, VC funds)

- How much financial, human and technical resources does the regulator have?

- What is the maturity of market players?

- What is the relationship between incumbents and new entrants (fintechs)?

Decision Tree

The decision tree is designed to diagnose gaps and areas of development that are faced by policymakers and regulators. It then provides a set of recommended approaches.

Country Examples

-

ApproachWait and See

-

Type of EconomyAE

-

Type of SandboxNone

-

Testing PeriodN/A

-

Legal SystemCommon Law

-

Type of RegulatorN/A

The Central Bank of Ireland does not have specific cryptocurrency regulations, and there is no prohibition of cryptocurrency activities within Ireland. Instead, the Central Bank of Ireland has taken a “wait-and-see” approach to the regulation of cryptocurrencies.

In March 2018, a speech made by the Director of Policy and Risk at the Central Bank of Ireland shed light on their approach: “To the extent that virtual currencies, ICOs, or those involved in their issuance or trading, are not subject to existing regulation, then the question arises: has the regulation fallen behind developments and needs updating. Or is it the case that these activities are just new examples of old types of activity and there is no need for further regulatory intervention, beyond making consumers properly aware of the significant risks through consumer warnings? Or might it simply be too early to say?

At the Central Bank, we are actively engaged with other European and international policymakers as we all try to figure out a way forward, including, for example, work at the ESAs [European Supervisory Authorities]. Given the cross-jurisdictional nature of virtual currencies and ICOs, we at the Central Bank welcome these efforts by the ESAs.”

In parallel to its approach, the Central Bank of Ireland has also endorsed a statement by the European Banking Authority, warning consumers of risks when undertaking transactions with virtual currencies (government-issued notices have been a common action across all jurisdictions and regulatory approaches)

-

ApproachTest and learn

-

Type of EconomyEMDE

-

Type of SandboxProduct, Policy

-

Testing PeriodUp to 12 months

-

Legal SystemCommon Law

-

Type of RegulatorSecurities Regulator

Safaricom: In 2007, when Safaricom approached the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) with their proposal to set up a mobile phone-based money transfer service, it raised a dilemma for the regulator. CBK was unsure how a financial service offered by a telecommunication operator could fit within the existing banking regulation.

Although the primary instinct of a risk-averse regulator would have been to deny permission to a largely unknown, new financial service, the CBK took into consideration the wide reach and potential this new service might have. At this time the Banking Act did not provide a basis to regulate payment products offered by non-banks, and CBK concluded that it had no clear authority over non-bank funds transfer, and hence would not interfere in allowing the telecommunications operator to launch the M-Pesa.

To allow a telecommunications operator to provide a transactional account, the CBK initiated some actions. First, a team of CBK legal experts developed Trust Account requirements invoking the Trust Law. The Central Bank also issued a letter of no objection, indicating that CBK would allow the service to launch, provided certain basic conditions were met including:

A. Appropriate measures are put in place to safeguard the integrity of the system in order to protect customers against fraud, loss of money and loss of privacy and quality of service.

B. The system will provide adequate measures to guard against money laundering.

C. Proper records are kept and availed to regulatory authorities in formats as may be required from time to time.

D. DM-Pesa will observe all existing laws governing its relationship with its agents and customers.

This letter empowered Safaricom to launch M-Pesa which attracted one million users in the first nine months and rose to four million in 18 months. The resounding success propelled Kenya into the poster child for creating enabling regulatory environments particularly those contributing to financial inclusion and economic growth.

Capital Markets Authority (CMA): The CMA has used the regulatory sandbox testing process to update regulations by allowing firms to experiment outside the regulatory framework. Upon exit from the sandbox, participants are either granted a license to operate in Kenya under existing regulations, or the CMA authorizes temporary operations until new regulations or guidelines are adopted according to section 12 and 12A of the Capital Markets Act.

For example, one participant, Pezesha, tested an internet-based crowd-funding platform through which investors can provide loan facilities for small and medium enterprises. The CMA uses these tests to create guidelines for debt-based crowdfunding in Kenya. Similarly, the Central Depository and Settlement Corporation (CDSC), the fourth firm to enter the sandbox, began testing its proposed screen-based securities lending and borrowing (SLB) platform for a period of five months starting April 2020. If the test succeeds, the CMA will update the current securities lending and borrowing regulations to include the screen-based model and will improve the uptake of the bilateral SLB product.

-

ApproachInnovation Hub

-

Type of EconomyAE

-

Type of SandboxUnknown

-

Testing PeriodUp to 12 months

-

Legal SystemCivil Law

-

Type of RegulatorCentral Bank

In France, there are three main authorities in the financial sector. Banque de France (the French Central Bank); Autorité de Contrôle Prudentiel et de Résolution–ACPR (the French Prudential Supervision and Resolution Authority)- an independent supervisory authority that operates under the auspices of the Banque de France; and Autorité des marchés financiers (AMF) the securities regulator in France.

In June 2016, the ACPR fintech-Innovation unit was set up to act as the single point of contact for innovative financial sector projects in both the banking and insurance sectors. The unit provides an interface, between project initiators and regulators while coordinating between the various ACPR departments within Banque de France on projects regarding payment services, as well as with AMF (through its Innovation and Competitiveness Unit) for projects regarding investment services.

The primary objectives of the ACPR fintech-Innovation unit are to support fintech players to better understand the nuances of the regulatory environment, and to facilitate the approval or authorization processes should the firm require a regulated status.

However, it also has a secondary objective to assess the challenges, risks, and opportunities related to technological innovation in the financial sector and the impact of this on financial stability. Learnings from this are then used to inform and contribute to global dialogue and research on the subject.

Demonstrating how an Innovation Hub can be complementary to other approaches, and support coordination between different regulatory bodies, the ACPR fintech-Innovation unit exists in parallel with the fintech Innovation and Competitiveness Unit of the AMF; with whom they conduct consultations with the private sector in both formal and informal settings to discuss regulatory and supervisory subjects related to fintech and innovation.

Another government initiative is the Banque de France’s Lab, created under the responsibility of the Chief Digital Officer, specifically to bring the central bank’s business lines closer to new practices and technologies. While more akin to an Accelerator or Regtech lab, the lab creates a space for collaboration and connects the Banque de France with innovative fintech start-ups, to experiment with new concepts and technologies in connection with the activities of the central bank.

-

ApproachInnovation Hub

-

Type of EconomyAE

-

Type of SandboxN/A

-

Testing PeriodN/A

-

Legal SystemCivil Law

-

Type of RegulatorBundesbank

The Bundesbank and the Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (BaFin) have taken coordinated steps toward fintech innovation. But, for several reasons, nothing that can be defined as a regulatory sandbox has been set up in Germany. Germany takes an innovation hub approach, as do most European Union’s member states. An important institutional consideration, not only for Bundesbank but also for BaFin, was based on their legal mandate.

Often the objective of using a “regulatory sandbox” is to proactively boost competition and, potentially, to relax regulatory or supervisory requirements to achieve this end. Yet, the promotion of competition is not a primary component of the German financial supervisors’ mandate, and it was felt that setting up a sandbox could not be justified under a strict interpretation of that mandate.

They were also concerned that supporting or admitting firms to a regulatory sandbox could generate reputational issues or conflicts of interest that would undermine the supervisors’ fulfillment of their overall mandate. A second consideration is that many of the pertinent laws and regulations around financial markets are developed and defined at the EU level due to the need to harmonize regulations across the area. When developing input for reform of EU legislation, authorities, including the Bundesbank and BaFin, coordinate through European Supervisory Authorities, in particular, the European Banking Authority in the case of banks and financial services providers.

The EU has no single specific “regulatory sandbox.” Instead, the European Forum for Innovation Facilitators (EFIF), a network of over 35 innovation facilitators (including innovation hubs and some regulatory sandboxes) was established; there, supervisors could, for example, share information and technological experience. Bundesbank and BaFin are members of EFIF. At the national level, the scope nevertheless remains to apply the principle of proportionality and a risk-based approach to supervision in a manner that eases constraints imposed on smaller fintech firms or firms that may pose less systemic risk. Accordingly, in several cases, the risks and size of new fintechs have defined supervisory practices. Interactions with fintechs have also led to adjustments in guidance and application of rules, as in the qualifications of directors, to adjust to the new fintech environment.

Bundesbank and BaFin already had other measures through which to contact and support the startup and fintech community, including regular “open door” consultation meetings where fintech could interact with officials to learn to better understand how existing regulations or supervisory practices would apply to their business model. In addition, the Bundesbank, BaFin, and the Ministry of Finance often come together to work on topics of mutual interest.

Another form of support to the fintech ecosystem in Germany is the Bundesbank’s Digital Office, which not only looks at trends in the market and interacts with incubators but also reviews how the central bank could use fintech to support its internal functions. The Digital Office has a partnership with Frankfurt´s TechQuartier, a melting pot for entrepreneurs and innovators from the financial industry. Through this partnership, the Bundesbank is in close contact with the fintech scene. Besides innovation challenges, workshops, and other events, the supervisory garage is a key feature of the partnership.

The supervisory garage allows fintechs to enter into a simple and direct exchange with Bundesbank officials and assists in navigating through regulations. The Bundesbank is also involved in considering the implications of new business models on market dynamics and stability. In 2016, BaFin launched a landing page for start-ups and fintechs. This landing page gives information on typical fintech business models and authorization requirements. In addition, BaFin launched a contact form for start-ups and fintechs on its homepage. The event, BaFin-Tech, hosted by BaFin, enables a broad dialogue with various stakeholders of the German fintech market. BaFin’s fintech unit, Technology-Enabled Financial Innovation, is engaged in identifying, understanding, and assessing fintech innovations and their relevance to and impact on the financial market. The unit aims to develop strategic positions, including the need for regulatory or supervisory action, regarding financial innovation. The fintech market in Germany is strong, and the market appears to be content with the role the regulators are playing.

-

ApproachInnovation Hub

-

Type of EconomyEMDE

-

Type of SandboxNone

-

Testing PeriodNone

-

Legal SystemCivil & Religious Law

-

Type of RegulatorBank Al Maghrib (BAM)

Faced with the digitalization of financial services and the advent of new electronic payment and fintech entrants, Bank Al-Maghrib (BAM) began, as early as 2017, to think about how best to address these developments, given its legal and regulatory framework. At first, BAM, with WB's assistance, studied the sandbox option. However, after some deliberation, this regulatory approach was abandoned for four main reasons: BAM considered that its position, in principle, was to regulate the institutions under its control fairly, not to regulate activities or institutions in an individualized manner.

- International experiences gathered were mixed and inconclusive, with few operational fintechs at the end of cohorts.

- The main applications received from fintechs were within the legal and regulatory framework. Other applications required a review of the banking law to carry out their activities.

- As the legislative processes are long and uncertain, even those firms that successfully exit a sandbox might have been unable to function unhindered in the market, creating an unnecessary burden for the fintech player.

In light of these concerns, BAM looked to other approaches, such as accelerators or incubators, and to the gradual implementation of more agile and responsive regulation that could provide a framework commensurate with the risks to consumers, financial integrity, and operational resilience. To do this, BAM has decided, as part of its work during 2019–2023 to formalize its digital strategy and to develop and promote an environment conducive to fintech development along two axes:

- Creation of the one-stop shop for fintech within the SMP Supervisory Directorate, with a focus on communication with the market, monitoring, and accreditation of fintechs.

- Integrating innovation into the central bank’s core activities by creating an Innovation and Digital Lab to foster innovation that supports the functioning and operations of the Bank.

-

Approachfintech Accelerator

-

Type of EconomyAE

-

Type of SandboxN/A

-

Testing PeriodN/A

-

Legal SystemCommon Law

-

Type of RegulatorBoE

The BoE launched a fintech Accelerator in June 2016 to help it harness fintech innovations for central banking purposes. It worked with small cohorts of successful applicants on short Proofs of Concept (PoC) in priority areas, such as cyber-resilience, desensitization of data, and the capability of distributed ledger technology.

Using an open and competitive application process, the BoE Accelerator helped the central bank create a framework to reach an array of fintechs who could collaborate directly with different business areas within the Bank. The aim was to be agile: testing the solution and the technology fast and if necessary, failing fast, to prove the concept within an average period of 3 months.

Main Functions of the BoE Accelerator The Accelerator provided the BoE with several tangible and intangible benefits; from enabling a faster path to engaging with start-ups and streamlining the product and testing environment, to the development of intelligence on growing market trends, and importantly gaining first-hand experience of a range of new technologies, while evaluating their application both to the Bank’s functions and in the wider market; through to being a catalyst for innovation within the Bank.

-

ApproachSandbox

-

Type of EconomyEMDE

-

Type of SandboxProduct/Policy

-

Testing PeriodUnknown

-

Legal SystemCivil Law

-

Type of RegulatorCentral Bank

Peer-to-Peer (P2P) lending platforms are a method of debt financing that directly connects individuals or companies with lenders. They were seen as an innovative model that could cater to those borrowers who might have been overlooked by traditional financial institutions.

The first online lending platform, Zopa, was founded in the UK in 2005 and Chinese companies followed suit in 2007, starting with PPDAI Group, with rapid growth since then. In China, P2P was touted as a pioneering model to help reform the mainland’s finance sector attracting money from investors by offering them high yields (8–12% compared to the much lower base interest rate offered by the government). The Chinese authorities decided to adopt a Wait-and-See approach as these platforms served the useful purpose of providing many small-scale businesses, micro-entrepreneurs, and at-risk individuals with the credit they could not previously access.

While this was potentially an accurate approach to use, allowing the market to grow faster and reach scale more so than any other jurisdiction, -according to the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), there were over 8000 P2P platforms and over 50 million registered users at the beginning of 2018 that together conducted 17.8 billion RMB worth of transactions making it larger than the rest of the world combined.

The fact that the regulation did not kick in at the right time caused some issues. By the end of 2015, before the issuance of any regulations or an established regulatory framework, there were roughly 3,448 P2P platforms in operation, 1,031 (roughly 1 out of 4) of which were categorized as either having difficulty paying off investors, being investigated by the national economic crime investigation department, or whose owners have disappeared with investor funds.

The regulators’ slow response to the aggressive growth led to multiple scams and controversies giving rise to the country’s largest Ponzi scheme. By 2016, the Chinese Banking Regulatory Commission reported that roughly 40 percent of P2P lending platforms were Ponzi schemes. This set-in motion a domino effect with widespread panic among the lenders leading to the shrinking of transaction BOX 5 values, which further prompted defaults preventing legitimate platforms from functioning. In a little over two years, the industry had gone from zero to about $218 billion in outstanding loans.

The initial hands-off approach began to taper off by mid-2015 when the PBOC provided a series of announcements leading up to China’s first regulatory instrument for online lending, the ‘Interim Measures on Administration of Business Activities of Online Lending Information Intermediaries’, issued in August 2016. In addition, Chinese regulators prepared a set of P2P market interim measures (constituted as the “1+3” system) in line with the overall internet finance development guidance.

Since then, Chinese authorities have ramped up regulations and have shut down many small and medium-sized P2P lending platforms across the country. They are also looking to incorporate a model of P2P marketplace lenders working alongside banks with the latter functioning as custodian partners. Since 2016, China continued to take a more cautious regulatory approach. In less than two years, regulations triggered the shutdown of the majority of P2P lending platforms from 2016 to 2018. By 2018, only 1,021 providers remained in place, and the Chinese government expects that number to further shrink to around 50–200 providers over time.

-

ApproachSandbox

-

Type of EconomyAE

-

Type of SandboxProduct

-

Testing Period12-24 months

-

Legal SystemCommon Law

-

Type of RegulatorSecurities Regulator

In Australia, the first iteration of the Sandbox was revealed by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) in December 2016. Any eligible fintech company needed only to notify ASIC of its intention to offer products and services within the Sandbox rules. No further approvals from ASIC or other regulators were required.

The relatively restrictive parameters of the Sandbox, however, resulted in limited participation with only one start-up utilizing the Sandbox in 7 months. ASIC, therefore, took further measures to improve the Sandbox, and the Government thereafter issued new draft legislation and regulations to create an enhanced Regulatory Sandbox. The new Sandbox provides a “lighter touch” regulatory environment to allow additional flexibility to fintechs that are still at the stage of testing their ideas. While safeguards remain the same in the new legislation, the key proposed changes include:

- Extending the exemption period from 12 months to 24 months.

- Enabling ASIC to grant conditional exemptions to financial regulations for the purpose of testing financial and credit services and products.

- Empowering ASIC to make decisions regarding how the exemption starts and ceases to apply.

- Broadening the categories of products and services that may be tested in the Sandbox, to include life insurance products, superannuation products, listed international securities, and crowd-sourced funding activities.

- Imposing additional safeguards such as disclosures, information about a provider’s remuneration, associations and relationships with issuers of products, and the dispute resolution mechanisms available.

The reform importantly allowed ASIC to control how exemptions are granted and withdrawn and required fintech firms to notify clients that they are using the exemption. Certain baseline obligations continue to apply during the course of the process i.e. the obligation to act in a client’s best interests, and obligations on handling client money and on preparing statements of advice where personal advice is provided. For credit contracts, these include responsible lending obligations, special rules for short-term contracts, limitations on fees, and unfair contract term rules. Breaching these obligations may result in the ASIC canceling a firm’s exemption.

-

ApproachSandbox

-

Type of EconomyEMDE

-

Type of SandboxPolicy

-

Testing PeriodVaries

-

Legal SystemCivil Law

-

Type of RegulatorCentral Bank

In 2004, taking an approach similar to the one used in Kenya, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) allowed two large telecommunications firms to test new mobile money products for consumers. At the time, it was a nascent market: there were no established regulations or models for mobile money. BSP allowed the telecommunications firms to proceed with testing new models of delivering financial services through nonbank entities, and BSP closely supervised the process. Five years later, in 2009, this experiment led to the issuance of “Guidelines on Use of Electronic Money.”

Later, BSP constantly dealt with numerous customer complaints making it challenging to ensure that they were all dealt with adequately and in a timely fashion. The central bank was heavily reliant on manual processes and relatively outdated technologies such as direct mail and call centers to field complaints or queries and provide timely resolutions.

The Use Case: To help solve for this problem, R2A worked with the central bank to develop a clear and detailed use case for a chatbot application and a complaints management system. They recognized that Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Big Data could have the potential to even out many of the pain points in complaints aggregation, processing, and analysis. The use case was advertised publicly, and firms were invited to submit a proposal on how they would conduct a Proof of Concept (PoC) to resolve the challenge.

The Solution: A selection committee that drew from global experts selected a vendor that best met the functional and design requirements of the use case. Some of the design elements included allowing consumers to file complaints through their mobile handsets via either an app or SMS and the ability to delegate all routine tasks to the chatbot such as initial screening and directing non-BSP complaints to the right institution. The solution ensured that human interaction and intervention were used for more complex or nuanced tasks such as the analysis of recurrent types of frauds and onsite inspections.

The Outcomes:

- The solution was estimated to have provided a time saving of 1 to 2 weeks per month for complaints analysis;

- It enabled BSP to have visibility over customers’ experience, which could then be used to improve the experience;

- The data and insights gathered through the chatbot could additionally be used to verify compliance with market conduct regulations and develop policies that are informed by knowledge of users’ needs and challenges.

-

ApproachSandbox

-

Type of EconomyEMDE

-

Type of SandboxUnknown

-

Testing Period2 years

-

Legal SystemCivil Law

-

Type of RegulatorCentral Bank, Financial Supervisor, Ministry of Finance

In Mexico - a civil law jurisdiction - a regulatory sandbox is one of many complementary initiatives under the nation’s fintech law that work together to build an enabling fintech ecosystem. Mexico enacted its renowned fintech law in March 2018 to encourage innovation and extend regulatory parameters to cover existing fintechs operating in the market. The law granted the various regulators the authority to supervise fintechs, set up a legal and regulatory framework for fintech institutions, establish a fintech supervision department within the Comisión Nacional Bancaria y de Valores (CNBV) to oversee crowdfunding and e-money and launch regulatory sandbox(s).

The sandbox, supervised by a sandbox team, works with both regulated and nonregulated entities to test innovations. In addition, the law launched an open banking initiative and allowed transactions to be made using certain cryptocurrencies, among other initiatives. With the law passed, the phased secondary regulations can be adjusted and updated to hone the specifics of the operation of the law and the sandbox’s inter-agency collaboration arrangements. These efforts achieved some early successes in building fintech expertise, encouraging active engagement between policymakers and fintech, and integrating policymakers and industry stakeholders within broader fintech forums domestically and abroad.

Mexico adopted an umbrella law on fintech (Ley para Regular las Instituciones de Tecnología Financiera) on March 9th, 2018, following months of consultation among public and private sector stakeholders- including banks, non-bank financial institutions, the Mexican fintech association, banking association, and academic institutions-and the approval from the bicameral legislature of Mexico. The Law sought to give further framing (and restriction) to fintechs focused on certain activities-particularly in payments, crowdfunding, and those using virtual assets as part of their business model. The Law itself introduces a general regulatory framework, which is intended to be adapted to the constantly evolving sector using secondary regulation to cover the detail of the implementation.

The Mexican Banking and Securities Commission (CNBV), the Mexican Central Bank (Banxico), the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit (SHCP), and other financial regulators were required to publish the corresponding enabling regulations within the 6,12 and 24-month periods following the fintech Law’s effective date. This approach was adopted due to the civil law mandate under which Mexico operates. The secondary legislation provides the flexibility necessary to adapt regulation to the changing environment without necessitating a change in the law. Its introduction has positioned Mexico as a progressive and attractive environment encouraging for fintechs, which can develop in a considered manner. The Law builds on six governing principles:

(i) Facilitating financial inclusion and innovation,

(ii) Ensuring consumer protection,

(iii) Safeguarding financial stability,

(iv) Fostering competition, and

(v) Protecting against anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism

(vi) Neutral approach to supervision via technology

To this end it has introduced:

- A legal framework for the authorization, operation, and supervision of fintech institutions domiciled in Mexico (Instituciones de Tecnología Financiera, ITFs) focusing on two particular types: crowdfunding institutions (IFCs) and electronic payment funds institutions (IFPEs).

- The legal basis for a Regulatory Sandbox environment for innovative companies, outside the established frameworks included in the law and regulations.

- The introduction of the concept of open sharing of data for non-confidential aggregate data and transactional data with consumers’ consent through the Application Programming Interfaces (APIs).

- A provision to recognize virtual assets and regulate their conditions and restrictions of transactions and operations in Mexico.

-

ApproachSandbox

-

Type of EconomyEMDE

-

Type of SandboxProduct. Thematic & Policy

-

Testing PeriodUp to 12 Months

-

Legal SystemHybrid System

-

Type of RegulatorCentral Bank, Securities Regulator, Office of Insurance Commission

In Thailand, three different regulators launched regulatory sandboxes: the Bank of Thailand (BOT), the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and the Office of Insurance Commission (OIC). Each sandbox covers a different aspect of the financial system: payments, remote identity verification, and insurance, respectively. The sandboxes, however, differ in approach, eligibility, and mandate.

The BOT sandbox focuses on new, “never-before-seen” innovations and thus far has focused on quick-response (QR) codes and cross-border payments. The SEC sandbox allows fintechs to test new eKYC (electronic know your customer) technologies, and the OIC sandbox has enabled insurers, agents, and InsurTech firms to test InsurTech innovations. The sandboxes also complement Thailand’s fintech hub, F13 (launched by the Thai fintech association), working together to develop a fintech ecosystem. The F13 hub provides space for fintech start-ups to test and validate their services with customers. As a result of these multiple initiatives, new regulations and initiatives were introduced for robo-advisory, peer-to-peer (P2P) lending, eKYC, and QR payments.

The BOT is using its regulatory sandbox to test a shared KYC and ID verification utility that relies on the National Digital Identity Platform (NDID) to verify and authenticate identity (BOT 2020). NDID is provided by National Digital ID Company Limited, which has shareholders from 69 companies, including Thai commercial banks, specialized financial institutions, securities companies, fund management companies, life insurance companies, casualty insurance companies, electronic payment service companies, the Stock Exchange of Thailand, and Thailand Post Company.

The test allows six commercial banks to sign up new customers into savings account products using a combination of facial recognition technology and the ID verification information customers previously provided to the bank they already use. The goal of the test, which is limited to opening savings account products during normal business hours, is to foster more convenient and more secure remote account opening for digital financial services. The BOT is monitoring the results of the test before making NDID functionality available more broadly to the financial sector. The test builds on a previous sandbox effort in which 12 commercial banks and payment services providers tested biometrics technology-facial recognition-to verify customer identity through eKYC. The test was conducted to develop further guidance on the use of eKYC regulation to comply with requirements on anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT).

Although fintech growth in Thailand is not directly attributable to the sandboxes only, since the launch of the various regulatory innovation facilitators, Thailand has shown some competitive outcomes in line with the “Thailand 4.0” national strategy to encourage innovation. For instance, Thailand’s Global Talent Competitive Index for 2019 moved to a rank of 66 out of 125 countries surveyed, as compared to 70 in 2018 and 73 in 2017. In addition, Thailand has experienced significant growth in the number of venture capital firms, angel investors, and fintech accelerators. Although direct linkage cannot be proven, the role of the BOT, OIC, SEC, and F13, combined with regulatory incentives (for instance, Thailand provides tax incentives to merchants who use card-accepting equipment) and stimulus through fintech accelerators, cannot be ignored.

-

ApproachSandbox

-

Type of EconomyEMDE

-

Type of SandboxProduct, Thematic

-

Testing Period12 months

-

Legal SystemCommon Law

-

Type of RegulatorCentral Bank

In 2018, the Bank of Sierra Leone (BSL) launched its Regulatory Sandbox Pilot Program to foster local fintech innovation and encourage the development of new products, technologies, and business models designed to improve financial inclusion in Sierra Leone.

The sandbox framework was coordinated in conjunction with the Sierra Leone fintech Challenge supported by FSD Africa and UNCDF. The fintech Challenge was intended to foster collaboration between regulators, nontraditional market players, licensed financial institutions, and other partners to pilot innovative products, services, or solutions in Sierra Leone’s fragile state context. Cash prizes, seed capital, and admission to BSL’s sandbox were offered to Challenge winners.

BSL announced the sandbox framework in July 2017 in connection with the fintech Challenge. A BSL committee drafted the preliminary framework and application process with the help of external advisers. BSL then solicited input on the draft from key stakeholders in Sierra Leone, including incumbent financial institutions and the local fintech association.

Based on this feedback, BSL revised the framework and provided written comments explaining its approach to the proposed amendments. The BSL Regulatory Sandbox admitted its first cohort in May 2018. The sandbox benefited from a combination of high-level executive support, a thorough public consultation process, and a dedicated sandbox team charged with managing all aspects of the project.

But the application evaluation, and subsequent design and evaluation of the testing plan, proved to be more onerous and time-consuming for the sandbox team than anticipated, particularly because of the large amount of time dedicated to each participating firm. The sandbox has matured and began serving as a primary point of contact for all inquiries on fintech innovation. The sandbox framework, likewise, has evolved into an open-admission format that allows firms to apply for testing at any point, rather than in specially designated cohort windows.

BSL has been constantly engaging with the industry through road shows, conferences, and even a radio show to raise public awareness, address initial questions, and improve the quality of sandbox applications.

-

ApproachSandbox

-

Type of EconomyEMDE

-

Type of SandboxPolicy

-

Testing PeriodVaries

-

Legal SystemCommon Law

-

Type of RegulatorCentral Bank, Securities Regulator

The financial sector in Hong Kong is regulated by separate, sectoral regulators: the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA), the Securities and Futures Commission, the Mandatory Provident Fund Schemes Authority (MPFA), and the Insurance Authority.

The Insurance Authority established its sandbox in December 2017, the same time that the Securities and Futures Commission and the HKMA announced their formation of new regulatory sandboxes or enhancements to existing sandboxes. All three sandboxes, at the time of the announcement, were to be linked together, providing a single point of entry for pilot trials of cross-sector fintech products. Coordination with the other regulators on fintech issues is via their existing memorandums of understanding (MOUs).

When a cross-sectoral issue has arisen, the lead authority tested the product in its sandbox and coordinated and communicated the results to its sister authorities. For example, the Insurance Authority used its sandbox to test the distribution of an insurance product via online banking channels by an insurance company that was part of a banking group. Compliance with both insurance and banking regulations (e-banking, agent banking rules, etc.) was checked before the product was allowed to graduate.

The HKMA initially launched its fintech supervisory sandbox (FSS) in September 2016 as a program for incumbent banks. During the first year of operation, however, HKMA received applications from technology firms requesting direct access to the FSS and soliciting feedback on emerging fintech projects.

Against this backdrop, HKMA upgraded to FSS 2.0 in 2017. This version includes expanded access for both incumbents and nonbank technology firms; an FSS Chatroom to provide streamlined access, feedback, and support for market participants; and increased formal coordination between HKMA, the Insurance Authority, and the Securities and Futures Commission on tests that may cut across multiple regulatory perimeters.

By the end of August 2018, HKMA had received around 170 requests to access the chatroom. Nearly 70 percent of these requests were made by nonbank technology firms from Hong Kong and overseas.

-

ApproachSandbox

-

Type of EconomyEMDE

-

Type of SandboxProduct, Thematic

-

Testing Period6 months

-

Legal SystemCommon Law

-

Type of RegulatorCentral Bank, Securities Regulator, Other Govt. Body

In July 2016, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), India’s central banking institution, created an inter-regulatory Working Group (WG) to study the scope and potential of fintech and review the regulatory framework with which the industry must comply. The WG included representatives from RBI, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority (IRDAI), and the Pension Fund Regulatory and Development Authority, as well as from select financial entities regulated by these agencies, rating agencies and fintech companies.

On February 8, 2018, the government committee, representative of all the financial sector regulators and select industry members, published its “Report of the Working Group on fintech and Digital Banking.” One salient recommendation of the WG was to introduce a regulatory sandbox, and it recommended the Institute for Development and Research in Banking Technology (IDRBT) as having the expertise to run a regulatory sandbox and innovation hub in collaboration with the regulators.

In response, the RBI, SEBI, and IRDAI all launched parallel sandboxes in 2019. While the basic premise of supporting and encouraging responsible fintech is common to all three, their designs differ somewhat, particularly regarding eligibility criteria and testing environments. While multiple sandboxes can be useful, they may also pose challenges for fintechs operating across sectoral boundaries and straddling the scope of authorities’ mandates.

The parallel operation of different sandboxes could introduce added layers of bureaucratic complexity for fintech firms that straddle more than one sector. Downsides can be minimized, and risks mitigated with effective interagency collaboration and coordination to align objectives and provide clear messaging to innovators. But differences in legal, regulatory, and supervisory practices and mandates may remain that are difficult to align through coordination alone. Effective cooperation may require alignment on new crosscutting regulations (on cloud computing or artificial intelligence, for example) or some degree of regulatory arbitrage between different business models.

The regulatory sandbox set up by the RBI has a dedicated staff of four to five personnel responsible for developing the enabling framework and defining the operation and structure of the sandbox.

For the first cohort, the team chose “retail payments” as a theme, with the explicit intention of spurring innovation in the digital payments space and helping to offer payment services to the unserved and underserved segments of the population. To support the application and eligibility process, they sought input from the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), an initiative of the RBI and the Indian Banks’ Association (IBA), with the primary aim of creating a robust infrastructure for India’s entire banking system focused on innovations in retail payments and the move toward a “less-cash” society.

-

ApproachSandbox

-

Type of EconomyEMDE

-

Type of SandboxCross Border

-

Testing PeriodUnknown

-

Legal SystemMixed

-

Type of RegulatorUnknown

The Pacific Islands Regional Initiative (PIRI) launched a regional sandbox in March 2020. PIRI, supported by AFI and UK aid, launched the Pacific Regional Regulatory Sandbox Guidelines to support fintech development and regulation across seven central banks, including: Banco Central de Timor-Leste, Bank of Papua New Guinea, Central Bank of Samoa, Central Bank of Solomon Islands, National Reserve Bank of Tonga, Reserve Bank of Fiji, and Reserve Bank of Vanuatu.

The sandbox is designed to remove barriers to innovation between the islands and to mitigate risks by allowing members to act as a regional bloc rather than individual markets. This concept can potentially help bolster expansion of interested fintechs to the wider Pacific regional market which has a total GDP of US$10.45 billion as of 2019.

It is expected that, in contrast to a national sandbox, this regional sandbox will help firms tap into a larger, more diverse customer base; reduce regulatory and legal bottlenecks; and ensure new business model sustainability and viability.

While it is too early to draw any conclusions concerning the successes of the PIRI sandbox, in general, regional approaches are aided by the geographic proximity of the participants, similarity in macroeconomic conditions, and presence of shared priorities - all factors that can support the development of effective cross-border sandboxes.

-

ApproachSandbox

-

Type of EconomyEMDE

-

Type of SandboxProduct, Thematic

-

Testing Period6 months

-

Legal SystemMixed

-

Type of RegulatorNational Bank of Rwanda (BNR)

The National Bank of Rwanda (BNR) set up its regulatory sandbox in 2018, as highlighted in Chapter IV of the official Gazette no. 14 of 02/04/2018, to facilitate developing and adopting innovative financial technology, specifically within the payments space. Since then, two further sandboxes have been created within BNR alone, one for micro-insurance and another for deposit-taking institutions.

In 2019, a World Bank team supported BNR with fine-tuning its regulatory sandbox using a phase 2 Sandbox Simulation exercise. The Sandbox Simulation exercise was attended by BNR key representatives from several departments, including Bank Supervision, Policy, Payments Systems Supervision, Insurance Supervision, and Financial Inclusion; representatives of two other regulators, Rwanda Utilities Regulatory Authority (RURA) and Kenya’s Capital Markets Authority (CMA), as well private sector incumbents and innovators, were also present.

In total, 21 individuals participated Before the detailed simulation exercise was conducted, the WB team presented for four days on global sandbox models and approaches to sandbox governance and processes. Using five case studies created uniquely for the Rwanda context, the simulation took participants through all aspects of the sandbox lifecycle, from application and evaluation through to test design and implementation, culminating in an exit strategy.

The simulation forced participants to review and design tests and supervision strategies for the realistic case studies, with the aim of integrating lessons learned into the policy framework. The results and learnings helped the BNR refine the goals and objectives of the sandbox, define and communicate clear and tangible objectives and instructions for innovators looking to apply to the sandbox, and highlight specific areas where the application form could be updated.

The exercise also supported the BNR in identifying which waivers they could consider without harming the regulator’s objectives and while the honing the governance structure in place around the sandbox, including the cooperation mechanisms between different regulatory bodies.

-

ApproachSandbox

-

Type of EconomyEMDE

-

Type of SandboxProduct/ Policy

-

Testing Periodnot specified

-

Legal SystemCivil Law

-

Type of RegulatorFinancial Sector Regulator

In 2018, Colombia’s regulator, Superintendencia Financiera de Colombia (SFC), initiated a legislative change to launch its InnovaSFC program to encourage financial sector innovation with targeted regulatory assistance.44 The program has three mechanisms: a hub to serve as a single contact point; the sandbox, or La Arenera; and a regtech mechanism to leverage innovations to help the regulator’s internal processes.

As part of the sandbox, the regulator issues a temporary, two-year fintech license for sandbox graduates before deciding whether to permanently adopt any linked regulatory changes. If adopted, the changes are communicated through external circulars, which help to familiarize the financial sector with updated practices. Using this mechanism, Colombia has thus far issued new regulations for cybersecurity, cloud computing, payments schemes, and QR codes and is in the process of issuing fintech licensing and new anti-money laundering rules.

-

ApproachSandbox

-

Type of EconomyEMDE

-

Type of SandboxThematic

-

Testing PeriodNot specified

-

Legal SystemCommon Law

-

Type of RegulatorCentral Bank

Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) introduced a specialized thematic track for its sandbox. Termed as a specialized sandbox, it is intended to accelerate innovations with clear potential to improve financial services. The specialized sandbox streamlined the application processes for thematic innovations, while the broader sandbox continued to provide wider coverage for other innovative solutions.

The first specialized sandbox focused on eKYC and digital onboarding in an attempt to evolve KYC regulation historically performed in person. Under the specialized sandbox, two fintech companies and seven banks tested new eKYC technologies.

One of the first participants of the regulatory sandbox, MoneyMatch - an online cross-border remittance service provider - offered peer-to-peer remittance services and tested digital onboarding by conducting multiple video conferences to verify potential clients. The firm created a platform to match individual buyers and sellers of currencies with a focus on SMEs who do a lot of cross-border transfers over the course of one day.

For verification, MoneyMatch used AI-powered third-party facial recognition. Using the sandbox for a controlled roll-out and to test the effectiveness of the eKYC process, MoneyMatch successfully graduated in June 2019, exiting BNM’s eKYC sandbox and receiving approval to operate and use its new KYC methods within the Malaysian market.

The sandbox results helped the BNM enable digital verification and develop new eKYC policies. In December 2019, the BNM issued an exposure draft proposing requirements and guidance for eKYC implementation.

-

ApproachSandbox

-

Type of EconomyAE

-

Type of SandboxProduct, Thematic

-

Testing Period6-12 months

-

Legal SystemCivil Law

-

Type of RegulatorCentral Bank

The Bank of Lithuania (BOL) launched its blockchain-based sandbox, LBChain, in March 2020, to accelerate the development and application of blockchain-based solutions in the financial sector and attract more fintechs to the country.

BOL is working with external service providers to build the LBChain platform, which allows firms to test blockchain-based solutions while guiding them on applicable regulations and providing temporary relief on some supervisory requirements. While the regulatory sandbox is in its early phase of operation, it has become the testing environment for several different types of financial products.

Of 21 registrations, 6 fintech companies from 3 different countries were deemed eligible based on criteria including genuine innovation, consumer benefit, need for testing in a live environment, readiness for testing, and a goal of providing financial services in Lithuania.

For its LBChain sandbox, BOL provides consultations on regulation as well as technical and technological support to eligible fintech companies to support the development of products into market-ready solutions.

These companies have used LBChain to test their products, including a KYC solution for AML compliance, a cross-border payment solution, smart contracts for factoring process management, payment tokens, a mobile POS and payment card solution, a crowdfunding platform, an unlisted share trading platform.

-

ApproachSandbox

-

Type of EconomyAE

-

Type of SandboxPolicy

-

Testing PeriodNot specified

-

Legal SystemHybrid System

-

Type of RegulatorOther Govt. Body

Upstart Network, a fintech that began to operate in 2016, uses both traditional underwriting information and alternative sources of information - such as employment history and educational background - to evaluate an individual’s creditworthiness. The Upstart platform pools this alternative data while applying computing and machine learning to identify relationships and evaluate creditworthiness that might not have been achieved using traditional assessments.

Concerns about the fairness in algorithmic lending, the use of nontraditional data, and the adherence to the fair lending laws set out in 1970 necessitated that Upstart engages with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFBP), a U.S. consumer regulatory agency that just launched its sandbox. Over some time, the CFPB reviewed the model using a series of tests; for example, it processed the same loan application using both traditional data and Upstart’s model with alternative data.

The CFBP issued the firm a no-action letter (NAL), referencing the application of the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) and its implementing regulation, for its use of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning in its credit underwriting and pricing models. A report by CFBP in August 2019 highlighted that the Upstart model increased the approval of borrowers by 27 percent relative to traditional models while offering 16 percent lower interest rates. Moreover, over the past year it has kept defaults in check and reached profitability; however, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on this initiative is yet to be seen.

As part of the NAL, Upstart has continued providing CFBP with simulations on credit reporting, further proving that AI can improve credit scores and credit approval. The sandbox tests have allayed the regulator’s concern over inherent bias in the alternative data and algorithmic decisions and have shown that Upstart operates in compliance with lending laws and regulations. Sandboxes can provide a useful (virtual) space for innovative start-ups to test new ideas and concepts by regulatory objectives. They play an important role in providing the concrete empirical evidence needed to make overarching decisions that lead to regulatory change.

When used with this purpose in mind, sandboxes can provide unmatched benefits to the policymaker. However, while early evidence suggests that sandbox programs can result in regulatory change, interviews with some policymakers suggest that change is often attributed to the open engagement between regulators and innovators and the specific guidance received by firms while in a sandbox. As illustrated in the benefits section below, some of these commonly cited benefits can be achieved using other, less resource-intensive, initiatives. It is thus difficult to quantify the direct impact of a sandbox on instituting regulatory change as compared to successes achieved with other innovation facilitators.

-

ApproachSandbox

-

Type of EconomyEMDE

-

Type of SandboxThematic

-

Testing Period6 months

-

Legal SystemCivil Law

-

Type of RegulatorCentral Bank

Established in 2018, the Bank Indonesia (BI) fintech Sandbox aims to provide a safe space to test Financial Technology Operators and their products, services, and business models. fintechs entering the BI sandbox must be listed companies registered with the bank and meet other common sandbox criteria, such as providing innovative and relevant services targeted toward Indonesian customers, readiness to test, and others. PrivyID was an early entrant to BI’s sandbox.

A member of the Indonesian fintech Association (AFTECH), PrivyID was registered by the BI as Indonesia’s first digital identity and legally binding digital signature solution provider. Prior to entering the sandbox, PrivyID provided banks with digital signature technologies for some financial services. However, digital signature solutions for credit card applications were not as yet legal. This prompted PrivyID to apply to the sandbox to test digital solutions to replace hand-written signatures for credit card applications. In early 2019, PrivyID submitted its application to BI’s sandbox.

The application process included a detailed interview with BI sandbox staff, adequacy requirement tests, and many follow-up information and documentation requests, all to a relatively tight timeline. The process as a whole took six months before PrivyID received the go- ahead to launch its new digital signature solution for credit card applications. Once PrivyID was in the sandbox, many banks were keen to partner with it. The new technology expedited credit card approval processes from three to five days to 15 minutes. Over the course of one year, PrivyID and financial service providers processed e-signatures for more than 50,000 credit card applications.

The sandbox provided other benefits to PrivyID. Inputs from Bank Indonesia helped PrivyID refine and adjust its solutions to better meet the needs of the consumer. For instance, PrivyID initially processed credit card applications by requiring users to send information to bank partners that then forwarded the application to PrivyID for verification. Once verified, PrivyID would message users (through SMS) with a unique user ID, a password, and a secure link for signature. However, some customers were unable to find their notifications or links for e-signature. This led PrivyID to include the added ability to use facial recognition against accredited identification documents with added one-time password controlled security methods that could also facilitate the digital signature.

PrivyID exited BI’s sandbox in August 2020 after successfully completing all the tests, including no signature or application failures. Since then, providers must still obtain explicit approval from BI to utilize PrivyID’s digital signature solution. Moreover, service providers are required to seek permits from OJK (the Indonesia Financial Services Authority), as the regulator for e-KYC, to employ PrivyID’s solution. While the product still has a low takeup level, the firm indicated that it was very happy with the process and had benefitted immensely from the close relationship with the regulator.

-

ApproachSandbox

-

Type of EconomyEMDE

-

Type of SandboxProduct/ Policy

-

Testing Period3 months

-

Legal SystemCivil Law

-

Type of RegulatorCentral Bank

In May 2018, the Central Bank of Brazil (BCB) launched the Laboratory of Financial and Technological Innovations (LIFT), a fintech incubator and a sandbox to accelerate the development of start-ups and accept submissions from early-stage innovators.

Fintechs entering the BCB’s sandbox are supported by participating organizations and LIFT partners, including the Federação Nacional de Associações dos Servidores do Banco Central (a Brazilian nongovernmental organization) and industry partners, including researchers, developers, specialists, and representatives from firms like Oracle, Amazon Web Services, IBM, and Microsoft.

Partners provide guidance, as well as products and services to support sandbox applicants with prototypes; in many cases, they partner with startups to launch in the sandbox and eventually in the Brazilian market.

This approach allows LIFT and the BCB to help stimulate entrepreneurship, increase competition, and introduce a new range of innovative solutions to enhance the Brazilian financial sector, such as increasing financial education and inclusion, making credit cheaper, modernizing legislation, and making the financial system more efficient.

-

ApproachSandbox

-

Type of EconomyAE

-

Type of SandboxProduct /Policy

-

Testing Period6 months

-

Legal SystemCommon Law

-

Type of RegulatorCentral Bank

To encourage fintech innovation in Singapore, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) launched a fintech regulatory sandbox in 2016.

PolicyPal, an insurance technology-based company that uses AI to digitize insurance, registered in the MAS regulatory sandbox in March 2017; following six months of testing, it was the first to graduate. PolicyPal and the MAS worked together to optimize insurance policy options for holders by assessing challenges and identifying gaps in insurance policies.

According to PolicyPal’s founder, the insurance sector grew rapidly in 2018, when digital disruptions in the traditional financial services sector created greater opportunities for InsurTech firms and insurers to introduce new business models into the market. Since PolicyPal entered the market, MAS has taken on Inzsure, another InsureTech company aiming to use its digital platform to provide end-to-end service and reduce transaction costs.

A few companies in the InsureTech space in Singapore have begun leveraging AI, blockchain technology, and internet of things (IoT) technologies, including companies in the region collaborating with the Singapore market.

-

ApproachSandbox

-

Type of EconomyEMDE

-

Type of SandboxThematic

-

Testing PeriodUp to 12 months

-

Legal SystemHybrid System

-

Type of RegulatorCentral Bank

A core objective of the Central Bank of Jordan’s regulatory sandbox is to contribute to the nation’s efforts to become a regional financial innovation and entrepreneurship hub by “encourage[ing] competition and increase[ing] effectiveness and security in money transfers.”

The sandbox interacts with Jordan’s national fintech hub to create a pipeline of incubated financial technology innovations. The sandbox links with other partner companies, like JoMoPay, Jordan’s national e-payment, and mobile payment platform, and with a range of innovation facilitators to encourage competition and stimulate entrepreneurship within Jordan.

In response to the COVID-19 crisis, Jordan released a specific cohort focused on solutions for consumers battling the crisis and introducing competition to plug potential gaps in the market.

-

ApproachSandbox

-

Type of EconomyAE

-

Type of SandboxProduct, Policy

-

Testing Period3-6 months

-

Legal SystemCommon Law

-

Type of RegulatorFinancial Supervisor

In May 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic led most of the world to go online, the FCA piloted a “digital sandbox” to allow firms to test and develop proofs of concept in a digital testing environment while receiving enhanced regulatory support to tackle the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic.

They are in the process of completing their first round of applications specifically focused on preventing fraud and scams, improving the financial resilience of vulnerable consumers, and improving access to finance for SMEs.

While the specifics are still being ironed out, access to data, a collaborative platform, and an API marketplace are all being considered. This supports the development of fintech products and services with a specific aim and end goal.

Interestingly the digital sandbox also gives observers the chance to participate in the sandbox, either to form partnerships with other firms, provide mentorship, or simply observe the process.

-

ApproachSandbox

-

Type of EconomyAE

-

Type of SandboxPolicy

-

Testing Period2 years

-

Legal SystemCivil Law

-

Type of RegulatorSecurities Regulator, Financial Supervisor

In early 2018, South Korea’s government designated fintech as a leading sector for innovation and has been implementing its Plan for Promotion of fintech Innovation. In January 2019, the government announced the following strategies to expand the fintech ecosystem: implementation of a regulatory sandbox; revamping outdated regulations; expanding investment in fintech; cultivating new industry sectors; supporting global expansion, and enhancing digital financial security.

This strategy involves deregulation measures including 2019 amendments to the Supervisory Rules on Electronic Financial Transactions and the Special Act on Support of Innovation of Finance (Finance Innovation Act). Significant changes under the Supervisory Rules include adaptations to enable cloud computing and cloud-based services for processing critical financial information. The Finance Innovation Act amendments include the following deregulatory measures:

- Regulatory exemptions through the sandbox for innovative financial services for up to four years;

- A one-stop-shop model through which the Financial Services Commission provides rapid regulatory advisory services to firms; and

- Core business outsourced to fintech companies without requiring separate regulatory approval each time under a “designated agent system.”

A preliminary evaluation of the sandbox as a part of the overall sector strategy suggests job growth in the fintech space, with 225 jobs added by 23 new firms. In addition, investment in the sector increased, with about 11 fintech firms attracting KRW 120 billion in investment as of 2019, and expansion of fintech firms to different global markets, specifically in Southeast Asia, the United Kingdom, Japan, and Hong Kong.

-

ApproachRegulatory Reform

-

Type of EconomyEMDE

-

Type of SandboxUnknown

-

Testing Period2 years

-

Legal SystemCivil Law

-

Type of RegulatorCentral Bank, Financial Supervisor, Ministry of Finance

In Mexico - a civil law jurisdiction - a regulatory sandbox is one of many complementary initiatives under the nation’s fintech law that work together to build an enabling fintech ecosystem. Mexico enacted its renowned fintech law in March 2018 to encourage innovation and extend regulatory parameters to cover existing fintechs operating in the market. The law granted the various regulators the authority to supervise fintechs, set up a legal and regulatory framework for fintech institutions, establish a fintech supervision department within the Comisión Nacional Bancaria y de Valores (CNBV) to oversee crowdfunding and e-money and launch regulatory sandbox(s).

The sandbox, supervised by a sandbox team, works with both regulated and nonregulated entities to test innovations. In addition, the law launched an open banking initiative and allowed transactions to be made using certain cryptocurrencies, among other initiatives. With the law passed, the phased secondary regulations can be adjusted and updated to hone the specifics of the operation of the law and the sandbox’s inter-agency collaboration arrangements. These efforts achieved some early successes in building fintech expertise, encouraging active engagement between policymakers and fintech, and integrating policymakers and industry stakeholders within broader fintech forums domestically and abroad.

Mexico adopted an umbrella law on fintech (Ley para Regular las Instituciones de Tecnología Financiera) on March 9th, 2018, following months of consultation among public and private sector stakeholders- including banks, non-bank financial institutions, the Mexican fintech association, banking association, and academic institutions-and the approval from the bicameral legislature of Mexico. The Law sought to give further framing (and restriction) to fintechs focused on certain activities-particularly in payments, crowdfunding, and those using virtual assets as part of their business model. The Law itself introduces a general regulatory framework, which is intended to be adapted to the constantly evolving sector using secondary regulation to cover the detail of the implementation.

The Mexican Banking and Securities Commission (CNBV), the Mexican Central Bank (Banxico), the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit (SHCP), and other financial regulators were required to publish the corresponding enabling regulations within the 6,12 and 24-month periods following the fintech Law’s effective date. This approach was adopted due to the civil law mandate under which Mexico operates. The secondary legislation provides the flexibility necessary to adapt regulation to the changing environment without necessitating a change in the law. Its introduction has positioned Mexico as a progressive and attractive environment encouraging for fintechs, which can develop in a considered manner. The Law builds on six governing principles:

(i) Facilitating financial inclusion and innovation,

(ii) Ensuring consumer protection,

(iii) Safeguarding financial stability,

(iv) Fostering competition, and

(v) Protecting against anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism

(vi) Neutral approach to supervision via technology

To this end it has introduced:

- A legal framework for the authorization, operation, and supervision of fintech institutions domiciled in Mexico (Instituciones de Tecnología Financiera, ITFs) focusing on two particular types: crowdfunding institutions (IFCs) and electronic payment funds institutions (IFPEs).

- The legal basis for a Regulatory Sandbox environment for innovative companies, outside the established frameworks included in the law and regulations.

- The introduction of the concept of open sharing of data for non-confidential aggregate data and transactional data with consumers’ consent through the Application Programming Interfaces (APIs).

- A provision to recognize virtual assets and regulate their conditions and restrictions of transactions and operations in Mexico.

-

ApproachRegulatory Reform

-

Type of EconomyAE

-

Type of SandboxNone

-

Testing PeriodN/A

-

Legal SystemCivil Law

-

Type of RegulatorN/A

Estonia, with a total population of 1.3 million people, has a burgeoning start-up scene: Tallinn, the capital, is home to roughly 435 fintech start-ups. To respond to the growing fintech sector while also managing the resource and opportunity costs required to establish a sandbox, the Estonian Financial Supervision Authority (EFSA) opted to establish the in-house fintech Working Group in 2016.

The Working Group operates much like an innovation hub. It operates as a single point of contact and is made up of an informal group of regulators, including representation from the central bank, the anti-money laundering (AML) regulator, and the securities regulator.

The members of the group provide fintechs with guidance on navigating the legal and regulatory system and also help gather knowledge and build the capacity of policymakers within EFSA. Based on the group’s interaction and information exchange with fintechs, it also works to develop proposals for regulatory adjustment. In the past, consultations have included data aggregation, payment services, and crowdfunding requirements.

Almost three years later, having successfully implemented necessary reforms (including strengthening the policy framework for research and development as well as innovation policy) and gathered the necessary market intelligence, the Working Group has unveiled plans for a sandbox to be established with the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD).

Impact Measurement Framework

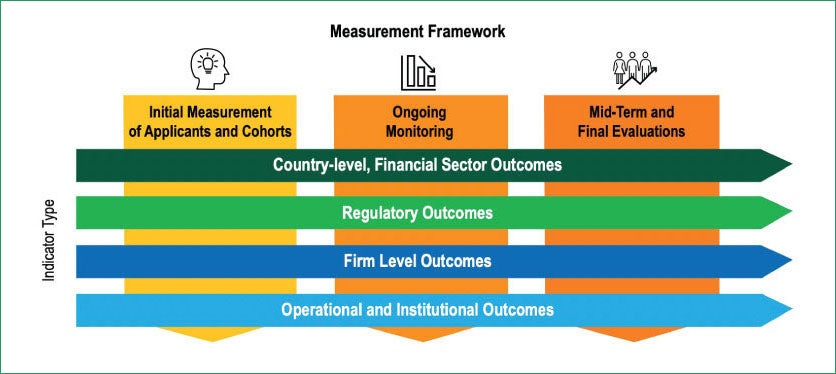

Evaluations should be done to understand if the innovation facilitator framework is fit for purpose—this introduces agility into the regulators’ processes. Having a clear objective and intended outcomes can underpin a facilitator’s success. Outcomes should be defined at multiple levels:

- country-level outcomes.

- regulatory outcomes.

- market- and firm-level outcomes.

- operational and institutional outcomes.