Overview

Introduction

Effective regulation and supervision are essential to ensure that benefits of financial sector innovation are realized, and at the same time, DFS providers identify, manage and mitigate risks in line with key regulatory objectives.

Policy Objectives and Impacts of Innovation

| Policy Objectives | Impact of Innovation – Potential Benefits | Impact of Innovation – Examples of Risks |

|---|---|---|

| Financial Stability |

|

|

| Financial Inclusion |

|

|

| Financial Integrity |

|

|

| Consumer Protection |

|

|

Overview

Defining Regulation and Supervision

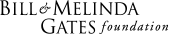

An enabling regulatory framework is the foundational first step for fostering inclusive DFS. For the regulatory framework to be effective, an appropriate supervisory framework needs to be designed and implemented to reflect the intent of the regulatory process.

Financial regulation is understood to mean the adoption and enforcement of the various laws and secondary rules (referred to in some countries as “regulations”) that govern financial institutions, whether adopted by the legislature, a financial regulator, or another policymaking body.

Financial supervision examines the soundness of financial institutions by evaluating entities, markets, systems, services and instruments against applicable laws, regulations, rules, and other standards. Financial supervision in practice entails a combination of market-level monitoring and institution-focused activities.

Approach to DFS Regulation and Supervision

Licensing straddles both regulation and supervision. Licensing criteria are set forth in law or regulation. The enforcement of such criteria and the decision to approve a licence application may be the responsibility of the regulator. Supervision of a licensed institution often includes an evaluation of conditions for a DFS provider to maintain its licence – or as a sanctioning power – the right to withdraw the licence.

This topic focuses on licensing considerations in the context of the regulatory framework.

How to Use This Section

The content in this section is designed to help regulators and supervisors design and implement a strong regulatory and supervisory framework by providing practical guidance. This section also covers principles for licensing in the context of DFS. The information is supplemented by country examples to illustrate different aspects of implementation. More detail is contained within Related Resources which form the basis for this section, and additional publications in the Further Readings.

This topic does not provide a comprehensive step-by-step manual on developing regulations or conducting each supervisory activity but highlights important aspects that impact their effectiveness and efficiency. It also recognizes three key limitations. First, regulatory perimeters and supervisory mandates may vary across jurisdictions. Second, some regulators and supervisors may follow a less linear approach than the one described, based on market context and emerging risks. Third, the content applies more generally to both prudential and market conduct regulation and supervision, yet there may be certain aspects and examples that are more relevant to one or the other.

Regardless of these limitations, the contents of this topic are designed to be adapted to country contexts based on policy priorities, powers and responsibilities, availability of quality data, and implementation capacity.

Overview

Key Aspects of DFS Regulation and Supervision

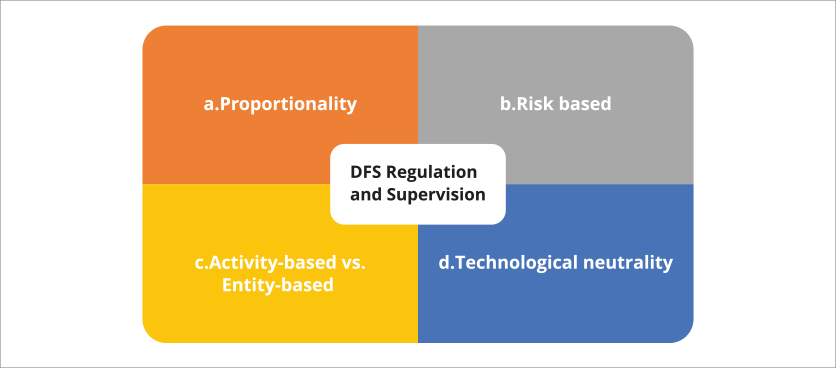

Four aspects of effective DFS regulation and supervision are of prime importance.

Key aspects of DFS Regulation and Supervision

Proportionality: Regulation, licensing and supervision must be scaled in line with the DFS provider’s business model, size, complexity, and risk profile—all of which determine the impact DFS providers have on the policy goals pursued. Lack of proportionality could impose excessive compliance costs that impact the provider’s ability to cater to underserved populations. It could also leave risks unchecked. Proportionality demands that supervisors have a solid knowledge of DFS business models, along with their benefits and risks. It should be applied in all phases—from regulation and licensing to supervision and enforcement.

Risk-based: Risk-based supervision (RBS) is closely related to proportionality. It requires using a methodology that systematically assesses risks and allocates supervisory resources. Financial supervisors worldwide broadly acknowledge that the risk-based supervisory approach helps them to achieve proportionality and effectiveness. Supervisory procedures and intensity should be adapted to the risks posed by DFS providers following systematic assessment of risks and the application of a balanced mix of supervisory tools. The risk-based approach helps authorities optimize the use of scarce resources and overcome some of the challenges they may face in supervising a growing DFS market.

Activity-based vs. entity-based: Regulatory requirements for the financial industry can be broadly classified as either activity-based or entity-based. Activity-based rules consist of requirements to be met by all institutions offering a given service (e.g. credit underwriting, payment services, investment intermediation, investment advice). Entity-based rules consist of requirements imposed on institutions with a specific licence or charter. Regulatory and supervisory frameworks for DFS may have to contain more activity-based rules than in the past given that the provision of DFS may involve a combination of entities (banks, non-bank financial institutions, and entities such as technology firms).

Technological neutrality: Regulation and supervision should focus on the activity and the risk it poses to policy objectives rather than the technology used. In practice, this would entail an in-depth understanding of the risks of underlying technologies and how those risks are connected to the activity being conducted. Considering numerous emerging technologies and their evolution, this ensures a level playing field amidst constant innovation. In practice, there may be limitations to this approach in initial phases of innovation (e.g. crypto-ecosystem) or in cases of potentially rapid adoption (e.g. artificial intelligence).

Striking the right balance can be a challenging task. As a result, approaches to regulation and supervision continue to evolve. Global approaches typically fall under one of the three common structures to address emerging risks in financial sectors:

- A twin-peaks approach to regulation and supervision with separate authorities responsible for (i) prudential regulation and supervision, and (ii) market conduct and consumer protection (for example, U.K., France and South Africa)

- A sectoral approach, where responsibilities are divided along industry lines (for example, banking, insurance, and capital markets—for example, in Hong Kong SAR, China, Kenya, and U.S.)

- An approach based on a single, integrated regulatory and supervisory authority (for example, Singapore, Switzerland).

Overview

Emerging Risks in DFS

Alongside the many benefits of DFS, it can potentially have adverse impacts on consumers as well as the financial system. The provision of DFS may add new risks to policy objectives of inclusion, stability, integrity, and consumer protection. The evolving DFS landscape also introduces new dimensions to existing financial sector risks (such as credit, liquidity, and operational risks) as DFS market participants redefine the nature of collaboration and competition in the financial sector.

The following non-exhaustive list provides an overview of selected DFS risks. Regulatory and supervisory authorities may evaluate these risks in their specific DFS landscape based on how DFS providers (i) interact with current and potential consumers, and (ii) build interconnectedness within the broader financial system.

Emerging Risks to Policy Objectives and Financial System

| Emerging Risks to Policy Objectives and Financial System |

|---|

| Gaps in Legal and regulatory framework: To the extent that DFS activities and DFS providers are novel, legal and regulatory responses (and resulting supervisory approaches) may not always be clear. See more |

| Cyber-risks: Susceptibility of financial activities to cyber-attacks is higher as products and services continue to migrate to digital platforms. This affects operational risks across the financial sector as different entities become more inter-connected and platforms are opened or shared. |

| Data governance: With growing customer information and digital interaction, data governance risk stems from getting the balance right and answering questions around ownership, usage, and sharing of underlying data. See More |

| Competition: Ensuring a level playing field between traditional financial institutions and DFS providers, and also amongst them, remains a challenge. The nature of the challenge is also evolving as the list of DFS providers expands to technology, telecom, and other businesses that provide or embed DFS. See More |

| Increased inequality: Although the benefits of DFS are often touted to help to improve financial inclusion of underserved consumers, DFS also poses risks in widening the digital divide. Large, vulnerable populations may not have access to sufficient mobile or internet services, and therefore new innovations may capture population groups that are already financial included. |

| Third-party reliance: Some DFS activities can increase third-party reliance within the financial system. Disruptions to these third-party services may pose wider systemic risks the more central these third parties are in interconnecting multiple systemically important institutions or markets. In some cases, the third parties may not be financial institutions (e.g., cloud services) and hence not subject to financial regulation and supervision. |

| Increased participation in financial market infrastructures: Innovative payment and settlement services within DFS may potentially involve wider participation in critical payment systems and infrastructures. Similarly, a growing number of DFS providers may have access to information within credit infrastructures. Greater participation may introduce additional governance, operational and financial risks in financial market infrastructures. |

| AML/CFT risks: Certain DFS that facilitate anonymity in platforms and transactions may be used to conceal or disguise money laundering or terrorist financing, and evasion of sanctions. |

| Excess volatility: A number of DFS activities are specifically designed to be fast. In some cases, provision of DFS may create or exacerbate excess volatility in the system, for example, in competitive environments with high speed and ease of switching between service providers. Regulators and supervisors may have to adapt faster and data-driven processes to monitor, measure and address such risks. |

Emerging Risks to Consumers

| Emerging Risks to Consumers |

|---|

| Broad Risk Types |

| Fraud: The risk that intentionally deceptive actions by an entity or person will cause a DFS consumer financial loss (e.g. SIM swap/mobile account takeover fraud, card or mobile app fraud). |

| Data Misuse: The risk that an entity or person uses a DFS customer’s data or information for purposes it is not intended for e.g. algorithmic bias, unfair practices). |

| Lack of Transparency: The risk that terms, conditions, fees, and other DFS features are not understood by a customer (e.g. undisclosed fees, complex user interfaces). |

| Inadequate Redress Mechanisms: The risk that a DFS user has no channel for complaints or complaints are not appropriately addressed (e.g. processes that are complex, slow and/or costly). |

| Cross-cutting Risk Types |

| Agent-related Risks: Risks emanating from a user’s interactions with the designated agent of a DFS provider (e.g. insufficient liquidity, unauthorized fees, discrimination). |

| Network Downtime: The risk that technological failure prevents a customer from using DFS (distributed denial of service attacks, interrupted transactions, power outage). |