Key Considerations in DFS Regulation and Licensing

Regulatory Decision Tree

Regulatory action can cover a wide span, from marginal changes to existing regulatory settings to implementing new bespoke frameworks. In some cases, existing frameworks are fit for purpose or need only a few amendments. In other cases, regulatory frameworks will need to be complemented by supplementary guidance.

It may also happen that existing regulations are not directly applicable to DFS but provide a basis from which to undertake the necessary changes to effectively regulate and supervise it (for example, through the introduction of new digital banking licenses in Hong Kong SAR, China, Republic of Korea, and Singapore).

Finally, in some cases, new bespoke rules are required to either officially ban (for example, initial coin offerings in China) or allow DFS activities or DFS provider types (for example, new e-money laws in Singapore and Hong Kong SAR, China or Indonesia’s regulations for lending platforms).

The regulatory decision tree below presents considerations which may determine the regulatory approach to DFS. The considerations covered are supplemented by specific topics on Competition Issues, Integrity & Security, Agent Networks and Innovation Facilitators.

Regulatory Decision Tree

Key Considerations in DFS Regulation and Licensing

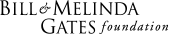

Regulatory Perimeter

Authorities must provide legal certainty through a clear definition of the regulatory perimeter and associated requirements which will be supervised and enforced. The regulatory perimeter is defined as the scope and applicability of the regulatory framework, including when and how regulation applies and what are the obligations and requirements to be met by each player. Even in cases when regulation is activity-based, it is always the provider, as a legal entity, who ultimately must meet the regulations.

There may be cases where the due diligence for DFS providers could be different than for regulated firms that are clearly within the regulatory perimeter, creating a risk of potential regulatory arbitrage. This could introduce contagion, dependency or even concentration risk that might not be mitigated in a timely manner.

In addition, the rapid pace of change may make it more difficult for authorities to monitor and respond to risks in the financial system (including general business risk), especially given the limited availability of relevant data and indicators.

This is of particular importance when it for comes to third party providers such as large cloud computing providers which have become pivotal players in DFS and even in the traditional financial sector, by providing critical services to multiple regulated entities.

Regulatory Perimeters in DFS Landscape

Moreover, efforts toward adapting legal and regulatory frameworks to new innovations often span across different ministries, departments and agencies, who often have parallel and overlapping supervisory and regulatory functions. Without proper coordination, including clear lines of communication with other relevant stakeholders and institutions involved (both domestically and internationally), policy frameworks may become fragmented, designed inappropriately, or result in policy gaps, all which can impede the development or diffusion of innovations and limit efforts to promote stability and inclusion.

The rapidly changing digital finance market may also require a new, holistic approach to regulation and supervision, particularly to address consumer risks. In such a responsible digital finance ecosystem approach, all key actors in the digital finance ecosystem—consumers, providers, policy makers, market facilitators— are required to share responsibility in mitigating risks to positive outcomes of DFS.

If regulators choose to use transition periods in which a temporary institutional arrangement for DFS supervision is adopted over a determined period of time, they should be limited and the intended final arrangement should be clearly communicated to the industry, to reduce regulatory uncertainty.

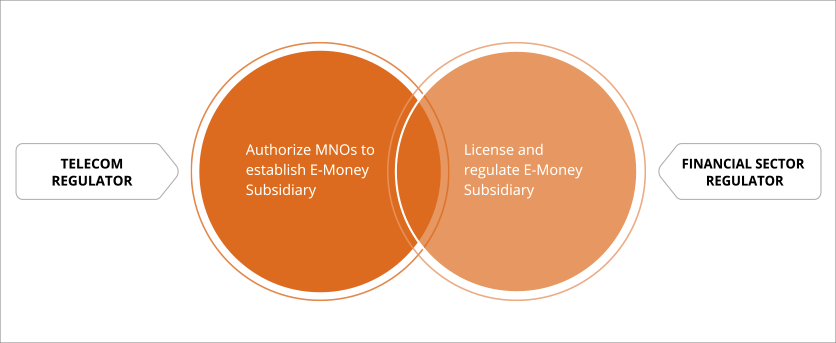

Regulating EMIs: Regulatory domains of telecom and financial regulator

Overview

There is a need to clarify the respective responsibilities of the telecommunications regulator and the financial regulator when mobile network operators (MNOs) are permitted to establish a subsidiary to issue e-money or offer similar services.

Delineation of responsibility

- The telecom regulator could be responsible for authorizing MNOs to:

- Establish a subsidiary for e-money business as a value-added service.

- Apply for a license from the financial regulator.

- The financial regulator could be responsible for licensing and regulating the e-money subsidiary.

Considerations

- Requiring MNOs to establish a subsidiary specifically for e-money business would limit the potential risk to the telecom parent in the event of the e-money subsidiary’s insolvency. This subsidiary EMI would be licensed by the financial authority.

- Having two separate business entities would also clearly delineate jurisdictions of the telecom regulator (MNO license) and financial regulator (e-money license).

| Issue | Financial regulator | Telecom regulator |

|---|---|---|

| Fair access to USSD and other communication channels | ||

| Fair access to retail payment infrastructure | ||

| E-money agent exclusivity | ||

| E-money interoperability | ||

| E-money prudential risks | ||

| E-money non-prudential (market conduct) risks | ||

| Permission to own and apply for a license for a e-money subsidiary from the financial regulator | ||

| Licensing of e-money subsidiary | ||

| Network Connectivity |

Country Examples

In Kenya, non-financial companies such as mobile network operators (MNOs) were historically allowed to conduct e-money business without having to establish a separate legal entity to act as an e-money issuer subject to prior authorization by the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK). They needed to have a separate business unit with separate management and accounting. Overall, MNOs were regulated and supervised by the Communications Authority of Kenya, while e-money activities were regulated and supervised by CBK.

The National Payment System Act 2011 and National Payment System Regulations 2014 established the framework for payment service providers (PSPs). Safaricom and Telkom Kenya received PSP licenses in 2016 and 2018 respectively, however, without transferring their mobile businesses into separate entities. Airtel has successfully transferred its mobile money businesses into a separate licensed PSP, Airtel Money, in 2022.

In Malaysia, WeChat Pay, owned by the big tech Tencent, is one of the largest EMIs. Similarly, Razer Pay and GPay, which are respectively owned by Razer (gaming company) and Grab (ride-hailing/food delivery company), have EMI licenses in Malaysia and in the Philippines.

In 2020, the consortium of Singtel (telecommunications company) and Grab was awarded a digital bank license in Singapore.

In Myanmar, EMIs, known as Mobile Financial Services Providers, are wholly owned by MNOs, large retailers, or technology companies. In all these cases, the central bank of the respective country is the supervisor of DFS providers (e.g., EMIs), regardless of their holding companies.

In Mexico, EMIs, known as Electronic Payment Funds Institutions (IFPE), are regulated and supervised both by the National Banking and Securities Commission (CNBV) and the central bank (Banco de México). Banco de México conducts payments oversight, and CNBV conducts prudential supervision.

Adapted from CGAP (2023)

Key Considerations in DFS Regulation and Licensing

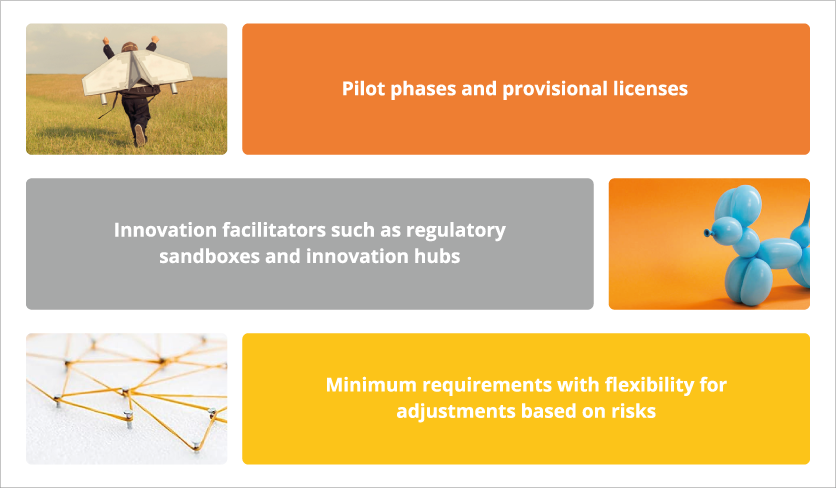

Emerging Regulatory and Licensing Tools

Newer regulatory tools can be more appropriate for introducing agility, giving better opportunities for both DFS providers and authorities to learn about key risks. Such approaches shift away from prescriptive licensing categories and respective requirements—where processes and requirements are better adjusted to each new DFS provider. Introducing flexibility may require legal and regulatory reforms and a profound cultural shift at regulatory and supervisory authorities.

New approaches to licensing

Key Considerations in DFS Regulation and Licensing

Licensing Framework

The rapid evolution in the DFS landscape requires faster and more flexible licensing and authorisation regimes. Most regimes follow laws or regulations which bring new types of DFS providers into the regulatory perimeter. However, licensing procedures may also be adapted to reflect (and mitigate) evolving DFS risks. For example, adjustments may include additional information for certain business models or enhanced requirements for data governance mechanisms.

Permitted and restricted activities: Entities that undertake only certain activities such as e-money issuance or crowdfunding are often restricted from undertaking other activities. Permitted activities are typically more narrowly defined than for banks or other financial institutions such as investment firms. For example, EMIs can usually offer payments, but not lending, while platforms offering P2P lending can provide some borrower research but may not be able to offer securities.

Restrictions on types of consumers: In some cases, the regulator may ban (or limit) the offering of a DFS product or service to certain types of users to protect them against sophisticated practices or complex risks.

Prudential rules: These include, inter alia, initial and minimum ongoing capital and liquidity requirements for digital activities that involve intermediation of client funds, safekeeping of entrusted funds when there is only a fiduciary role such as in the case of non-bank EMIs, and adapted disclosure and regulatory compliance.

Governance requirements and conduct: These rules set requirements on the composition of the management body and fit and proper criteria for shareholders and managers. In a few cases, simpler procedures may be acceptable provided they are transparent and effective, and that management is subject to fit and proper controls (that is, checks on the specific skills and knowledge related to technology applied to finance).

Integrity rules: These include AML/CFT requirements adapted to digital services, including virtual and remote account opening without the need to present physical identity documents. These adapted AML/CFT rules—often predicated on account, transaction, and balance limits to ensure low-risk profiles of clients—are supported by recent guidance from the Financial Action Task Force on digital ID and the use of a risk-based approach to CDD with regard to electronic and digital payment options.

Agents: DFS providers may wish to use agents to broaden their reach and penetrate rural, less densely populated areas, and other underserved areas. Depending on the type of activity, the agents may (or may not) be authorized and. if permitted, subject to certain restrictions in their activities and geographical locations. These restrictions and processes should be adapted to the risk profiles of the agents’ activities.

Data privacy and protection: Data governance is gaining increasing regulatory relevance in the context of DFS. It can often be found in specific licensing frameworks (for example, in e-money frameworks), general guidelines for financial service entities, and in national data protection laws. In the latter case, a data protection authority usually has joint jurisdiction over the financial service entities. The regulation of data-protection risks, however, must be balanced, as data policies that are too stringent could prevent beneficial innovations such as inclusive credit based on data analytics, impose competitive disadvantages to those that collect the data, or prevent customers and businesses from sharing information to obtaining loans, insurance, or other financial services.

Consumer protection: Minimum consumer protection rules and requirements can also be introduced at the licensing and authorisation stage. This can be done by establishing mechanisms or adopting proportionate approaches to maintain a minimum level of relevant safeguards and protection for new DFS providers.

In addition to new licenses, authorization procedures can cover a range of other situations, depending on a country’s regulatory framework:

- transfer of significant ownership of DFS providers

- mergers or acquisitions of DFS providers

- a new product or activity by DFS providers

- opening or closing a new channel or service point by DFS providers

- increasing or reducing the capital of DFS providers

- hiring or dismissing executives of DFS providers

- changes in the bylaws of DFS providers

- the cancellation (withdrawal) of the license to operate

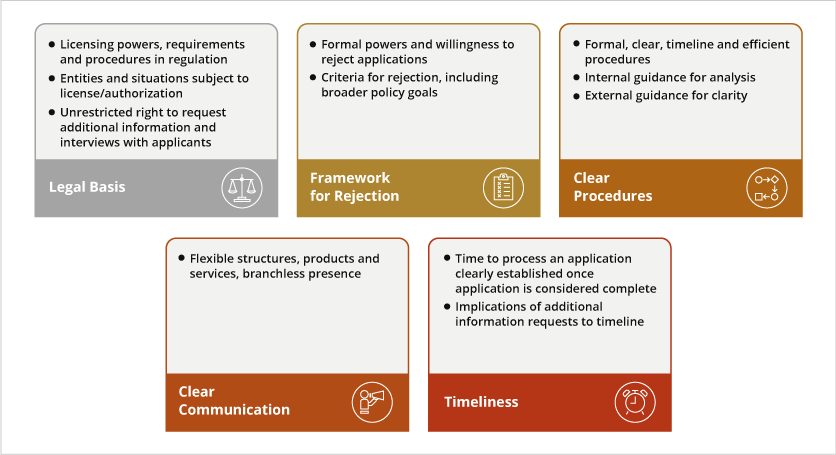

There are a few elements that make up a strong licensing framework which not only allows authorities to conduct thorough analyses of applications, but also benefit the DFS provider and the users, for increasing transparency, accountability, and certainty.

Components of a strong licensing framework

Key Considerations in DFS Regulation and Licensing

Licensing Procedures

Licensing procedures should be as clear, transparent, and efficient. They may include the following steps:

Step 1: Identify licensing phases (e.g., initial authorization and final approval): In the case of applications for becoming a new DFS provider, many – if not most – countries divide the licensing process into two phases: initial authorization and final authorization. The process and requirements of each phase should be made clear to applicants.

Step 2: Determine relevant licensing category. Most countries require different types of DFS providers to obtain a license prior to starting operations. Different types of businesses fall into different “licensing categories” (e.g., EMI, payment service provider, payment initiation service provider, account information service provider, crowdfunding platform operator, robo-advisory service provider, virtual asset service provider, peer-to-peer lending platform operator). The licensing requirements for each licensing category should be made clear to applicants.

Step 3: Analyze business plans. DFS providers should be required to present a business plan covering a minimum number of years. At least two aspects should be assessed by supervisors during licensing: quality (completeness, coherence and whether the plan is realistic) and the feasibility and viability of the proposed business.

Step 4: Carry out an initial meeting. It is good practice to call at least one meeting with the applicant, for their representatives to explain their background, intentions, overall strategy to enter, grow and compete in the market, the target clientele, and other highlights of their business plan. The DFS provider may also be required to make product demonstrations.

Step 5: Adopt a licensing decision. Supervisors should not grant a license simply because the application is complete. Granting a license means being satisfied with all the aspects analyzed during the licensing process. Also, supervisors may consider, in granting or rejecting to issue a license, broader policy goals, such as financial inclusion, competition, consumer protection, efficiency and safety of the financial system.

Other good practices within licensing procedures include gathering regular feedback from DFS providers and internal departments about the process, establishing processes for inter-departmental approvals of applications, improving internal guidance and written procedures for licensing staff, and maintaining a digital information system to record particulars of licensing applications which can be made accessible to relevant regulatory and supervisory staff.

Country Examples

The Central Bank of Brazil introduced adaptations in the licensing and authorisation regime. The enactment of Resolution 4,656 on April 26, 2018 attributed P2P lending companies the status of financial institutions, enabling them to operate in the Brazilian market without relying on incumbent financial institutions. The Central Bank of Brazil also issued Circular 3,898 in May 17, 2018, which determines the procedural rules for establishing P2P lending companies.