Within the DFS landscape, providers, users, and the interaction between them has changed significantly. On one hand, DFS has leveled the playing field between traditional banks and emerging Fintech businesses, diluting the impact of competition issues such as high switching costs or limited product innovation. On the other hand, increased competition has brought about new policy and regulatory concerns. For example, telecom operators may have acquired significant market power in e-money products in many markets. New technical interdependencies may have introduced systemic risks to financial stability. An increase in providers and users may have opened gaps in market conduct regulation and consumer protection frameworks.

E-Money Competition Issues

USSD Access

USSD Access

Overview

Issue

If an MNO is directly competing in or has a direct or indirect financial interest in the EMI market, refusal to supply communications services could harm competitors.

Data is typically only useful for smartphones. Most e-money services not delivered via smartphones use USSD, which displays as an interactive menu on the mobile.

Limited competition in offering DFS through USSD impacts women more, as they have higher dependence on USSD (Next Billion, 2021)

Typically, USSD access is governed by agreements between EMIs and MNOs. In many countries, this access has been an issue. However, regulatory reforms and market innovations are proving critical to leverage the potential of USSD access (see country examples).

USSD Access

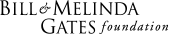

Example Of A USSD Transaction

User enters USSD short code (e.g., *159#) and presses ‘phone’ to ‘call’ the USSD number. The menu then displays:

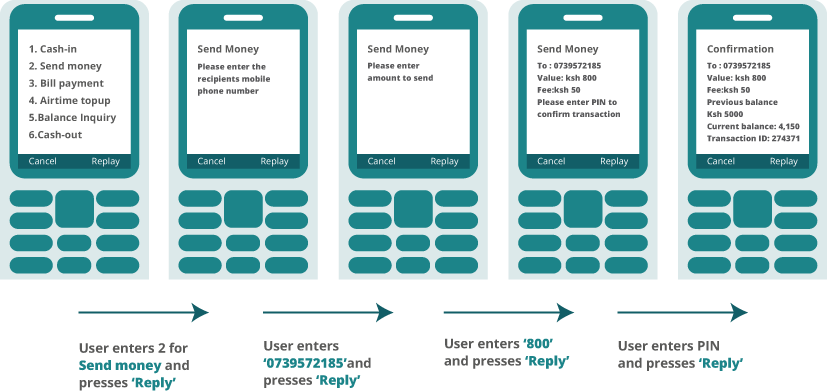

The system elements involved in USSD – direct FI-to-MNOs connection. There are multiple bilateral agreements between EMIs and MNOs, with different T&Cs, thus impacting market competition.

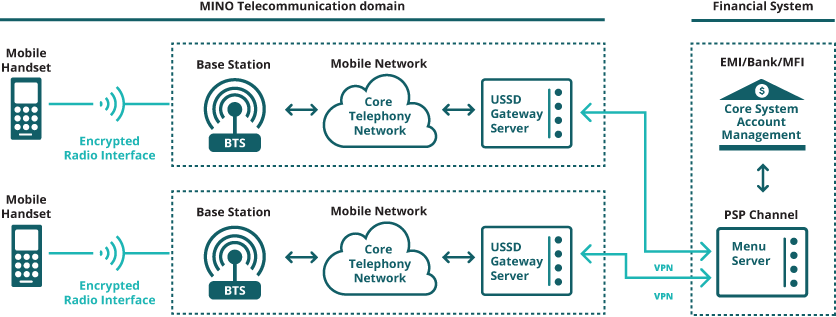

The system elements involved in USSD – MNOs connected via an Aggregator, which may wield significant power. Its ownership and functioning can impact market competition.

USSD Access

COUNTRY EXAMPLES - Ussd Access For Dfs+ Services

USSD access is increasingly becoming critical to offer advanced DFS and additional services.

The limits on non-MNOs’ access to USSD has made it harder to offer innovative products and services to customers. MNOs are not required to open up their USSD and are reluctant to do so.

Bilateral arrangements for USSD access have led to limited awareness about competing e-money issuers. Recently, Equity bank has revamped its USSD offering a unified service across mobile networks.

Ajua gives businesses unique USSD codes to receive payments, get feedback and offer discounts to their customers.

Ezee Money sued the MNO MTN for refusing access to its USSD gateway. The Commercial Court determined that MTN violated its duties under the Communications Act, ordered MTN to pay a fine, and issued a permanent injunction against such anti-competitive behavior in the future.

Zoona sued the MNO MTN for refusing access to its USSD gateway. The Competition and Consumer Protection Commission found MTN to have been engaging in anticompetitive behavior and fined MTN 2% of its annual turnover. The decision was appealed but dismissed.

Financial Sector Deepening Zambia and Zazu deliver financial literacy courses via mobile phones through USSD, SMS, and voice.

Through M-Pesa's USSD menu, savings group leaders can create account, add members, contribute to from their M-Pesa wallet at no extra cost, view account balances, can also request a loan automatically. It has been made interoperable, giving full access to members of other networks.

Insurance provider OKO has leveraged mobile money by integrating its service in Orange Mali’s USSD menu, providing a seamless digital journey for customers.

Private sector innovation

Stax allows consumers in Africa to buy airtime and transfer funds between accounts via automated USSD codes.

USSD Access

Issues And Possible Responses

| Issue: | Possible to address by: |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

USSD Access

Risk

Discriminatory pricing can be abusive if undertaken by a firm with significant market power. MNOs with such market power may engage in discriminatory USSD pricing to:

- Discourage competition in the e-money sector by:

- Offering low- or no-cost USSD services to affiliates.

- Charging high prices to competitors.

- Maximize profits by charging high prices for access to a required resource for offering e-money to the mass market.

USSD Access

Considerations

- As a first measure, financial regulators could require MNOs to price USSD services exactly the same for related and unrelated EMIs. However, enforcement could be challenge owing to tendency of opaque pricing. Thus, ensuring transparency will be the key.

- Telco regulators also could review complaints regarding USSD pricing and share EMI-related complaints with the financial regulator. An institutionalised coordination mechanism will be crucial in this regard.

- Setting USSD floors and/or ceilings requires a detailed inquiry into industry costs and could impede market development. Given the inherent costs and risks, regulators may wish to consider setting prices only if market-based efforts are unsuccessful, after thorough consultation and cost-benefit analysis.

- Financial and telco regulators could sign an MoU governing e-money cooperation and mandatory consultation. They could then jointly review complaints regarding USSD pricing and consider potential responses, as appropriate.

USSD Access

Country Examples - Discriminatory USSD Pricing

In Madagascar, telecom companies are reportedly practicing anticompetitive behavior by limiting financial institutions’ access to the USSD channel and by keeping tariffs high. There is a need to ensure USSD access at fair prices.

In Nigeria, despite regulator's mandate of flat fee for USSD services, consumers are reportedly still being charged excess fee of USSD services.

In Nigeria, since March 2021, USSD services are charged at a flat fee of N6.98 per transaction, replacing the prevailing per session billing structure. However, consumers are reportedly still being charged excess fee.

MNOs in Kenya and Tanzania are zero-rating USSD costs for partner banks while charging their competitors full price. However, Competition Authority of Kenya requires transparency in pricing of USSD services, to place banks and telcos on same footing.

Kenya has negotiated Pricing with Individual MNOs. In 2017, following intervention by Kenya’s Competition Authority, Safaricom agreed to reduce USSD session charges from KES 5 (USD 0.04) to KES 1 (USD 0.01).

MNOs in Kenya and Tanzania are zero-rating USSD costs for partner banks while charging their competitors full price. However, Competition Authority of Kenya requires transparency in pricing of USSD services, to place banks and telcos on same footing.

In Uganda, an inquiry commissioned by the Communications Commission concluded that Airtel and MTN’s USSD prices “are set at excessive rather than competitive levels…”

In Peru, the telecommunications regulator (Osiptel) requires MNOs to offer non-discriminatory pricing for USSD access. To help ensure this, Peru requires MNOs to set up a separate legal entity for e-money issuance.

In Colombia, MNOs must provide access to their channels (including USSD) to e-money issuers on a non-discriminatory basis. The telco regulator can accept and review complaints regarding price and quality on a case-by-case basis.

In India, in April 2022, the Telecom Regulatory Authority decided that the subscribers will not be charged for USSD for mobile banking and payment service, to protect the interests of the USSD users and to promote digital financial inclusion.

In addition, India has created a National Unified USSD Platform (NUUP) to enable USSD access for all banks.

E-Money Competition Issues

Quality of Service

Quality of Service

Quality of Service – failure causes

Issue

Failure to complete USSD interactions (sessions) results in user frustration as well as uncertainty as to whether transactions have completed

Examples of USSD session failure issues affecting user transactions include:

- Session timeouts.

- Dropped sessions.

- Insufficient number of stages per USSD session.

There are, however, different reasons why a session may not complete, only some of which are related to the MNO’s delivery of a USSD session (MNO QoS)

For example:

- Customer may abandon a transaction (user issue).

- Customer may move into a network dead zone during session and lose connectivity (network service issue).

- EMI may not respond (provider issue).

- Network may fail during the session (network issue).

Quality of Service

Quality of Service – Voice vs. USSD

Issue 1

USSD QoS issues are different from voice QoS issues, so voice QoS performance measures cannot be directly applied to USSD.

Some voice call and USSD session failure modes are different

- Failure to hand over from one base station to another: For voice, this is determinable from network statistics. USSD sessions cannot be handed over, so moving between cells is seen as a loss of contact.

- Session timeouts: Voice calls cannot timeout. USSD session timeouts can be determined, but there are multiple potential causes.

Issue 2

Some QoS issues are directly comparable while others are not, so USSD performance measures must be carefully designed to be both measurable and attributable.

Common voice call and USSD failure modes

- Inability to establish a call or USSD session: This is a common failure, but is not determinable from network statistics as the network ‘never finds out’ about the attempt.

- Mid-call and mid-USSD session failure: Loss of communication due to network failure.

Quality of Service

Quality of Service – Active Discrimination

Risk 1

Provision of lower-quality service to competitors by an MNO (or cartel) with dominant or significant market power can negatively impact competition.

Examples of active USSD quality of service (QoS) degradation include:

- Session length reduction.

- Bandwidth throttling to USSD gateway.

- Claimed unavailability by the USSD gateway.

- Limitation of number of concurrent sessions in USSD gateway.

Risk 2

Telco regulators should have

- The means to test for service manipulation.

- The power to sanction MNOs and require MNOs to restore full contracted service.

Manipulations can be found through testing:

- Most manipulations can be independently tested for from USSD test devices that transact over USSD, without actually internally auditing the USSD arrangements in the MNO.

Quality of Service

Country Examples

In 2016, the Communications Regulatory Commission issued draft regulations proposing the USSD QoS requirements, such as 99% of USSD sessions to be successfully completed. The final issued regulations did not include USSD QoS requirements. Enforcement of such requirements would face challenges with respect to attributability

Econet’s Ecocash holds more than 90% of the mobile network market. Its dominance in both the mobile network and mobile money markets has led to significant congestion, eroding consumer experience with both services.

The Telecom Regulatory Authority has issued the Mobile Banking (Quality of Service) Regulations.

It specifies time frames within which telcos are required to deliver messages between banks and consumers via SMS, USSD and IVR modes.

It prescribes benchmarks for response time, delivery of error and success conformation messages, transaction updates, and financial transaction messages.

It also provide for number of steps within which transactions should complete.

Quality of Service

Quality of Service

Analysis of regulatory approach

Quality of Service Standards when established to address USSD quality of service (QoS) must be measurable and attributable.

Measuring Quality of Service (QoS)

- In practice, it is difficult to enforce QoS standards such as Colombia’s draft requirements.

- When a USSD session with an EMI fails, there are many possible reasons, some of which are related to the MNO’s QoS and others due to elements such as:

- Users being too slow or abandoning sessions.

- USSD aggregators having performance and reliability issues.

- EMIs themselves being slow to respond or not responding at all.

- Unless the reason for failure can with certainty be attributed to the MNO, fairly measuring and enforcing MNO performance with respect to QoS Metrics is not possible.

Quality of Service

Considerations

- There is currently no publicly available failure cause analysis of USSD to use as a basis for setting QoS standards for MNOs and USSD aggregators. However, ITU has released a report on Methodology for measurement of QoS: Key Performance Indicators KPIs for Digital Financial Services.

- There are many elements where failure could lead to a failed USSD session, including the handset, the mobile network, USSD aggregators, data communication lines between the MNO and the EMI, the USSD menu server, and the EMI’s own systems. While customer faces similar discomfort irrespective of failure node, each element in this chain would need its own QoS standard.

- Failure cause analysis should only be undertaken if it is coupled with a determination of

- whether the cause is measurable/discernable.

- if so, whether it is attributable to a specific party.

- A QoS standard for USSD-delivered and other mobile financial services could be jointly developed by telecommunications, financial and consumer protection regulators. They could jointly review complaints regarding QoS and consider potential responses, as appropriate.

E-Money Competition Issues

Interoperability

Interoperability

Overview

Issue

Dominant e-money providers often resist efforts to promote interoperability (typically to maintain a competitive advantage, but sometimes for other reasons such as prioritization of resource allocation).

Interoperability can be beneficial, but issues such as

- Timing

- Technical and commercial models.

- Role of authorities are very important and country-specific.

Interoperability is not a panacea. Many markets achieved high levels of e-money uptake without interoperability (e.g., Ghana, Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda), while many interoperable markets initially low e-money uptake (e.g., Indonesia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Sri Lanka). Thus, timing, market size, and resource availability, are key determinants of interoperability.

Interoperability

Considerations

- In many cases, a market-driven approach to interoperability will ensure that the timing, technical model, and commercial model for interoperability make sense for EMIs. However, existence of dominant players may delay interoperability due to vested interests.

- Efforts by regulators to dictate the technical and commercial models for interoperability may result in an approach that is not commercially viable and lacks provider buy-in. However, at times, this may be required for greater consumer welfare.

- With respect to timing, regulators may wish to strike a balance that encourages investment in the early stages of market development, while monitoring the market for signs that lack of interoperability is hampering competition and/or market development, or adversely impacting consumer welfare.

- If regulators determine that lack of interoperability is a key barrier to competition and/or market development, they could first engage with EMIs to develop a mutually agreeable plan for implementation of interoperability within a reasonable timeframe.

- If market-led solutions in a well-developed market are unsuccessful due to resistance from incumbents, regulators could consider a more interventionist approach that is carefully designed to avoid disincentivizing investment and innovation. Cost benefit analysis of possible regulatory interventions will be the key.

Interoperability

Arguments for mandating interoperability

Ease of use

Interoperability can make it easier for customers to use e-money and other DFS.

Competition

In mature markets with a dominant provider, lack of interoperability can serve as a barrier to effective competition, prevent innovation, and may lead to abuse of dominant position.

Cost

By increasing competition and streamlining cross-net transfers, interoperability could eventually lead to lower customer costs.

Investment

Mandating interoperability in the early stages of market development could disincentivize investment by first movers that perceive this as a threat to their ability to recoup initial investments.

Opportunity cost

Implementing interoperability requires significant time and resources, which could affect other initiatives aimed at promoting market development.

Commercial viability

Mandating the technical and/or commercial model for interoperability could result in a solution that is not commercially viable nor scalable.

Interoperability

Country Examples

Option #1: Require interoperability to be technologically feasible at low cost

The TCRA required MNOs’ systems to have the capacity to be interoperable and adhere to international standards. TZ’s major e-money providers voluntarily interoperated Payment scheme interoperability quickly led to an increase in cross-net transfers. In 2022, the BoT is likely to launch the Tanzania Instant Payment System, an interoperable system that enables money transfers in real-time between banks and other DFS providers.

Option #1: Require interoperability to be technologically feasible at low cost

The NPS Regulations require PSPs to use interoperable systems. In 2017, the country’s e-money providers agreed to interoperate within three months. Eventually, interoperability went live in 2018. In 2022, Kenya launched first phase of merchant interoperability allowing mobile payments across telco networks.

Option #1: Require interoperability to be technologically feasible at low cost

Legislation in 2017 mandated mobile money providers to interoperate among themselves and banks through a central switch. To do this, the existing interbank hub, Gh-Link, was upgraded in May 2018 to allow mobile money providers to connect. Simultaneously, GhIPSS launched awareness programmes with stakeholders, resulting in 400% jump in interoperable mobile money transactions in six months.

Option #2: Mandate interoperability but be flexible regarding business model and timing

- After initially setting strict timelines (by 2013) for interoperability, in 2014 the National Bank of Rwanda (NBR) issued an Interoperability Policy in which it recognized that different payment systems are at different stages of market development. Since then, the NBR has engaged with e-money providers to promote interoperability. Two of the three major providers (Airtel and Tigo) piloted interoperability in 2015, but the largest (MTN) did not join. In August 2018, it was reported that the three major e-money providers were seeking regulatory approval to launch interoperable services.

- In 2019, the National Interoperability System, RSwitch, was expected to be launched. In 2021, a draft law mandating interoperability was proposed. However, some challenges remain.

Option #2: Mandate interoperability but be flexible regarding business model and timing

Interoperability is being mandated by the State Bank of Pakistan through introduction of the Asaan Mobile Account. It has also launched Raast, a new instant digital payment system, offers sector-wide interoperability, allowing government bodies and all financial institutions to seamlessly integrate and make digital payments

Option #2: Foster interoperability through stakeholder cooperation

- As early as 2013, the Bank of Uganda’s Mobile Money Guidelines recommended that, to facilitate full interoperability, mobile money service providers should utilize systems capable of becoming interoperable with other payment systems in the country and internationally.

- In 2017, the Bank of Uganda mandated immediate interoperability between MMPs over a period of a few months. This led two of the country’s major MMPs to initially use an aggregator before connecting bilaterally in 2019. However, they continue to use third parties for interconnection with smaller MMPs.

- Interoperability across telecom and banking networks is still awaited in 2022. Efforts by the Uganda Bankers Association and regulators such as Bank of Uganda to create national switches should see this happen in the short term.

Option #3: Mandate the timing, technical model, and commercial model for interoperability

- Per Circular BPS/DIR/GEN/CIR/01/014, EMIs were required to connect to the national central switch for real-time credit-push instant payment.

- However, in a 2016 test, ¾ of interoperability transactions were unsuccessful. Reasons for not enabling interoperability include cost, fear of inability to recoup investments, loss of competitive advantage, and perceived lack of industry readiness.

- As per 2021 Mobile Money Framework, mobile money operators are required to connect to the National Central Switch for the purpose of ensuring interoperability of all schemes in the system. However, it is yet to realise the benefits.

Option #3: Mandate the timing, technical model, and commercial model for interoperability

In 2021, the Reserve Bank mandated e-money issuers to give the holders of full-KYC prepaid payment instruments (PPIs) interoperability through authorised card networks (for PPIs in the form of cards) and UPI (for PPIs in the form of electronic wallets).

Option #3: Mandate the timing, technical model, and commercial model for interoperability

In 2022, Nepal’s central bank directed all digital payment service providers to implement interoperability within the next six months in what is seen as a key decision to compete with traditional methods of financial service delivery.

E-Money Competition Issues

Branding and Data

Branding and Data

Overview

Issue 1

Should EMIs operated by MNOs, banks, or “superplatforms” (e.g., Google, Facebook, WeChat) – whether directly or via a subsidiary – be permitted to use their branding and data for the EMI service?

Arguments for permitting use of branding and data

- Incentivizes investment by the parent company.

- Parent company may offer better customer service to protect overall brand reputation and based on available data.

- Customers may feel more confident adopting service if they trust the parent company.

Arguments for prohibiting use of branding

- Could create confusion regarding legal status of e-money service and associated protections (e.g., applicability of deposit insurance).

- Enabling companies to leverage their brand and data in a parallel market could offer a competitive advantage that some might deem unfair.

- Could refuse to share data and deny access to potential competitors.

Issue 2

Should EMIs operated by MNOs, banks, or “superplatforms” (e.g., Google, Facebook, WeChat) – whether directly or via a subsidiary – be permitted to use their branding and data for the EMI service? How can abuse of their dominance be prevented?

Considerations

- Allowing established MNOs, banks, super-platforms, and others to use similar branding for their e-money service could promote uptake and incentivize investment. However, this should happen with customer consent and compliance with data protection norms.

- Where applicable, properly disclosing to customers that e-money and similar services lack comparable protection to bank products (e.g., deposit protection) could help ensure that customers are not misled by similar branding.

- Clearly labeling agent locations could help to ensure that customers are aware that they are not interacting directly with parent company staff.

- Unnecessary over-regulation preventing platforms from operating in DFS market could restrict innovation and impede consumer welfare.

Branding and Data

Country Examples

Platforms’ databases are not easily replicable. This, in turn, can drive exclusionary behavior by dominant firms, such as limiting competitors’ timely access to data, preventing others from sharing data and inhibiting data portability. A platform may exert similar pressure on customers by driving up switching costs or by resisting interoperability and retaining transactions strictly within its own digital ecosystem.

WhatsApp Pay has been tested in India for just over two years but is yet to receive regulatory approval to expand services nationwide.

In addition, the third-party app providers are required to ensure that the total volume of transactions initiated through their respective Unified Payment Interface applications do not exceed 30% of the total volume of transactions in the country during the preceding three months.

Data ownership Is too concentrated in Pakistan and needs to be shared using mandated standards.

Banking Business Proclamation

Part Two, Art. 3.2: No person shall use the word ‘bank’ or its derivatives as part of the name of any financial business unless it has secured a license from the National Bank.

Regulation of Mobile and Agent Banking Services

9.2.5: In branding agent network, financial institution shall avoid use of words like bank, microfinance, financial intermediary, microfinance bank or any other word that might suggest that the agent by itself is a financial institution.

E-Money Competition Issues

Open API and Open Banking

Open API and Open Banking

Open API

Application Programming Interfaces (APIs)

Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) are interfaces that enable machines to communicate with one another:

- Private APIs are interfaces between a closed network of computers.

- Public APIs enable providers to allow access to carefully selected outside parties.

- Open APIs are public APIs with automated, streamlined onboarding processes to enable outside parties to quickly

- Access and integrate with a provider’s interface.

- Test and launch connected services.

Open APIs can make it much easier for Fintech firms and others to connect to EMIs and other DFS providers, thereby catalyzing innovation in the DFS space.

How open APIs can foster innovation

By dramatically reducing the time and cost for outside developers to integrate with DFS providers, open APIs can foster innovation, extend customer outreach, and increase revenue.

- With traditional public APIs, developers are selected through a lengthy manual process that requires significant face-to-face interaction and bespoke paperwork.

- With open APIs, developers can register online, test their product using an online “sandbox”, and request authorization through an automated, streamlined process, reducing approval times from months to days.

- Shifting from traditional public APIs to open APIs can attract small, innovative fintechs and rapidly grow the market for a DFS provider’s core products.

Examples:

- In Nov 2018, MTN Uganda launched its MoMo API to facilitate development and integration of applications using MTN Mobile Money for collections, merchant payments, disbursements, and remittances. By May 2021, the program was live across 12 African countries, with over 900 partners.

- The GSMA Mobile Money API is an initiative developed through collaboration between the mobile money industry and the GSMA. The initiative aims to increase adoption of the mobile money API through dedicated engagement with mobile money providers and support for ecosystem vendors.

Open API and Open Banking

Country Examples - Open API

In early 2021, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) defined standards for data sharing, including requirements for accessing data and APIs. The release of this framework moved Nigeria into a new phase of competition in the sector.

India has developed India Stack, which is the moniker for a set of open APIs and digital public goods that aim to unlock the economic primitives of identity, data, and payments at population scale. Its rapid adoption by billions of individuals and businesses has helped promote financial and social inclusion in India.

In 2021, Bank Indonesia launched the National Open API Payment Standard (SNAP) as well as sandbox trials of Quick Response Code Indonesia Standard and Thai QR Payment interconnectivity. This is expected to create integration, interconnectivity and interoperability among API operators, thus driving payment system efficiency.

Open API and Open Banking

Open Banking

Open Banking gives individual customers the power to allow third parties to access their financial data. Potential benefits include:

- Competition: Requiring banks and other payment account providers to let customers share data can facilitate competition for customers’ business.

- Innovation: Open Banking can enable Fintech firms to harness the power of data analytics to develop innovative financial products, such as collateral free credit, either directly or in partnership with other licensed financial service providers.

- Inclusion: With fuller picture of customers’ financial lives, providers can better assess customer needs & identify opportunities for improved financial health and inclusion.

Open API and Open Banking

Country Examples - Open Banking

In January 2016, the EU published the Revised Payment Services Directive (PSD2). PSD2, which was implemented in September 2019, PSD2 mandates banks and other financial institutions to give third-party service providers access to consumer transaction accounts based on the account holders’ consent.

In February 2016, the UK developed initial Open Banking standards aimed at standardizing how banking data should be shared and facilitating the creation of an Open Banking ecosystem. The OBIE Directory is managed by the Open Banking Implementation Entity, which oversees Open Banking implementation in the UK.

Nigeria’s open banking regulatory framework (2021) established principles for data sharing across the banking and payments system to promote innovations and broaden the range of financial products and services available to bank customers.

Under Australia's Open Banking Initiative since 1 July 2020, Australia’s bank customers can give permission to accredited third parties to access their savings and credit card data.

Since 1 November 2020, they can also give permission to accredited third parties to access mortgage, personal loan and joint bank account data. This will enable bank customers to search for a better deal on banking products or to keep track of their banking in one place.

Saudi Arabia is putting its 2021-introduced open banking policy into practice as part of the country's "Vision 2030" plan.

The design phase covers the Open Banking ecosystem (technologies and processes) and to the definition of a governance involving market participants. This is followed by the Implementation Phase to develop frameworks, technology building blocks and rollout activities including testing with financial market participants, and enhancement of customer awareness.

National Banking and Securities Commission of Mexico (CNBV) open banking initiative focused on 3 phases.

In the first phase, the initiative was related with the standardization and sharing of open data (specifically, the location and services offered by ATMs), for the time being. The second phase is related to standardization of transactional data. This is data related with movements in deposit accounts managed by banks, financial cooperatives and microfinance institutions. Phase 3 of open banking/finance includes standardization of the transactional data of credit.

In March 2021, the Bank of Ghana launched a regulatory sandbox pilot to help promote the development of the fintech sector, including open banking. As a result, Ghana is a country to watch as open banking grows in popularity and the global economy speeds up.

In 2020, the South Africa Reserve Bank collaborated with several government agencies and the Intergovernmental Fintech Working Group to establish The Innovation Hub, which aims to advance experimentation and innovation in fintech, including developing open banking infrastructure.

India has kickstarted its approach to Open Banking by creation of a new licensed entity called Account Aggregator (AA) and allowed them to consolidate financial information of a customer held with different financial entities, spread across financial sector regulators. AA acts as an intermediary between Financial Information Provider and User for sharing information through APIs.

Open API and Open Banking

The World of Open Banking

Open API and Open Banking

Considerations

- Open APIs and open banking offer great potential for fostering innovation and promoting the development of digital financial services for low-income customers around the world. However, risks of data misuse and breach remains.

- At the same time, open banking initiatives are in the early stages of development, so a consensus around good practices and standards does not yet exist.

- Financial authorities could monitor the experiences of early adopters of open banking initiatives and evaluate the readiness of their financial sector (and their supervisory capacity) to launch similar initiatives. They should engage with stakeholders, experts, and consumers to assess risks and benefits.

- Concurrently, policymakers could work to create an enabling environment for Fintech innovation to prepare for a world of open APIs and open banking, through practices like sandbox and regulatory impact assessment.