Setting up DFS Supervision

Creating a Risk-based Supervision Approach

Risk-based supervision is the key to supervisors achieving statutory policy goals, assuming that resources, capacity, and skills are limited. The RBS methodology allocates supervisory attention and time (i.e., intensity of supervisory activities and enforcement measures) according to a systematic evaluation and risk prioritization. The intent is to rationalize efforts to achieve greater effectiveness and efficiency. This makes it easier for supervisors to strike a balance among the policy objectives of financial inclusion, stability, integrity, competition, and consumer protection.

Designing the DFS supervisory framework

DFS supervisors can follow three initial steps to set a strong foundation for risk-based DFS supervision.

Resource for Step 1: Examples of supervisory objectives and risks mapped to policy goals

Purpose: Undertaking a mapping exercise is useful to inform the overall supervisory approach to DFS, including the choice of organizational structure. This exercise is also useful to build a comprehensive view of the main DFS risks to help identify the data needs and design reporting requirements, and to help authorities identify areas where inter-agency coordination is needed. Ideally, the mapping would be done in the early stages of designing DFS supervision. However, it is also useful for supervisors who are already undertaking DFS supervision. For instance, the mapping could be done before the beginning of the next supervisory cycle to adjust the annual supervision plan, and to identify gaps in the current activities or reporting requirements. This type of mapping is a practice relevant to any supervision, not restricted to DFS providers.

How it works: Mapping the supervisory objectives and risks to policy goals requires answering the following questions:

- What are your policy goals (based on your statutory mandates)?

- What is the priority level of these different goals?

- What specific supervisory objectives will make you attain the priority goals?

- What are the risks to achieving your supervisory objectives?

Note that risks can be posed not only by individual providers, but also by market conditions and dynamics in regulated financial industries, and by unregulated institutions and third parties working with regulated providers.

Frequency: Mapping can be conducted periodically, during the annual supervisory planning process, or at the end of each supervisory cycle, to inform the next period.

What this document offers: This document provides a few examples of policy goals, supervisory objectives and risks mapped to those goals. It is not exhaustive, and it does not offer a recipe. Its intent is to merely illustrate the mapping process, and to help supervisors set up or improve their risk-based approach. There are other potential policy goals (e.g., ensure financial stability and curb financial crime), which will vary across countries, and there could be other supervisory objectives under each of the policy goals used in the example below. Moreover, there would be more than just two risks per supervisory objective.

Example 1

Policy goal: Ensure safety of the national payment system

- Supervisory objective 1: Ensure reliability

- Risk 1: Poor telecommunication services

- Risk 2: Poor operational risk management at providers

- Supervisory objective 2: Ensure resilience of the national payment system

- Risk 1: Ineffective continuity and contingency arrangements at providers

- Risk 2: Obstacles to cross-border data flows

- Supervisory objective 3: Foster collaboration on cyber security

- Risk 1: Resistance to data sharing

- Risk 2: Lack of data security standards

Example 2

Policy goal: Increase efficiency of the national payment system

- Supervisory objective 1: Achieve interoperability

- Risk 1: Lack of technical standards

- Risk 2: Resistance to interconnect or interoperate

- Supervisory objective 2: Achieve cost-effectiveness

- Risk 1: Excessive interchange fees

- Risk 2: Overlapping installed capacity

Example 3

Policy goal: Foster competition

- Supervisory objective 1: Curb anti-competitive practices

- Risk 1: Predatory pricing

- Risk 2: Contractual clauses/practices that bind merchants

- Supervisory objective 2: Foster innovation

- Risk 1: Unbalanced entry or operating requirements

- Risk 2: Challenges posed by incumbents on innovators

Example 4

Policy goal: Protect financial consumers

- Supervisory objective 1: Ensure effective disclosure

- Risk 1: Disclosures unadjusted to the digital environment

- Risk 2: Misleading advertisement

- Supervisory objective 2: Ensure fair business practices

- Risk 1: Abusive contractual clauses

- Risk 2: Unfair treatment of unauthorized transactions

- Supervisory objective 3: Ensure effective redress

- Risk 1: Ineffective internal complaints handling

- Risk 2: Discrimination against women

Example 5

Policy goal: Expand financial inclusion

- Supervisory objective 1: Increase transaction account ownership

- Risk 1: Burdensome account opening procedures and requirements

- Risk 2: Prohibition of account opening through digital means

- Supervisory objective 2: Expand physical outreach of financial services outlets

- Risk 1: Weak agent network management

- Risk 2: Exclusivity agreements

- Supervisory objective 3: Reduce the gender gap in financial services usage

- Risk 1: Persistent algorithmic biases against women

- Risk 2: Gender gap in mobile phone ownership

Resource for Step 2: Examples of impact indicators

Purpose: The purpose of using impact indicators is to help prioritizing DFS providers and DFS risks that will be included in the initial risk assessment, when setting up a risk-based supervisory approach (RBA). After this initial assessment, the annual supervision workplan would be updated according to a combination of these indicators with other information. Using impact indicators is a common practice in any supervision, not restricted to DFS providers.

Details: Impact indicators indicate the potential severity of the consequences in the event of the materialization of the risks posed by DFS providers. Making a parallel to prudential banking supervision, the failure of a bank that holds the majority of the total loan portfolio would have a more severe impact than a failure of a smaller bank. The impact indicator, in this example, would be “share of the total loan portfolio”. Impact indicators are not the only method to prioritize DFS providers in an RBA. In the next steps of implementing RBA, impact indicators are used alongside probability indicators that point to the likeliness of risks materializing (for instance, a provider offering complex products to unsophisticated customers). Impact indicators are simple and often the first type of indicator used in RBA, using whatever data is already available in the early stages of RBA implementation. Later on, when the risk assessment and scoring methodology are built, supervisors end up combining impact and probability indicators in the same framework.

How it works: For each risk identified in the mapping exercise, supervisors would answer the following key question:

- What factors would lead to worse consequences in the event of risk materialization?

Frequency: The identification of impact indicators is to be done prior to the initial risk assessment in the process of building the RBA to DFS supervision. These indicators can later be adjusted in the process of continuously improving the risk-based methodology.

What this document offers: This document offers some examples of impact indicators linked to a few supervisory objectives and risks. It is not exhaustive and not a recipe for every country. Each jurisdiction needs to identify its policy goals, supervisory objectives, risks, and impact indicators, according to the local context. The aim here is to illustrate the concept of impact indicators and the process of identifying them (which will determine the data needs and the reporting regime put in place).

Supervisors doing this for the first time may want to focus on collecting indicators for which the underlying data already exist. There is no need to use a perfect set of impact indicators from the start. It is possible that the available data will not allow the use of important impact indicators for every risk. Also, it is important to note that one indicator can be relevant for multiple risks. Finally, none of the examples below are exhaustive. Each policy goal can have many more supervisory objectives, risks and impact indicators than the ones listed below.

Example 1

Policy goal: Ensure safety of the national payment system

- Supervisory objective 1: Ensure reliability

- Risk 1: Poor telecommunication services

- Impact indicator 1: Number of customers in areas with patchy telco services

- Risk 1: Poor telecommunication services

Example 2

Policy goal: Increase efficiency of the national payment system

- Supervisory objective 1: Achieve interoperability

- Risk 1: Resistance to interconnect or interoperate

- Impact indicator 1: Number of exclusive agents

- Impact indicator 2: Number of merchants

- Impact indicator 3: Number of customers

- Risk 1: Resistance to interconnect or interoperate

Example 3

Policy goal: Foster competition

- Supervisory objective 1: Curb anti-competitive practices

- Risk 1: Predatory pricing

- Impact indicator 1: Value of agent commissions/fees

- Impact indicator 2: Value of transaction fees

- Impact indicator 3: Transaction fee revenue to total revenue

- Risk 1: Predatory pricing

Example 4

Policy goal: Protect financial consumers

- Supervisory objective 1: Ensure effective disclosure

- Risk 1: Point-of-sale disclosures unadjusted to the digital environment

- Impact indicator 1: Number of new digital loans

- Impact indicator 2: Number of new e-money accounts

- Risk 1: Point-of-sale disclosures unadjusted to the digital environment

- Supervisory objective 2: Ensure fair business practices

- Risk 1: Abusive contractual clauses

- Impact indicator 1: Number of customers

- Risk 2: Unfair treatment of unauthorized transactions

- Impact indicator 1: Number of digital payment transactions

- Impact indicator 2: Number of digital payment customers

- Risk 1: Abusive contractual clauses

- Supervisory objective 3: Ensure effective redress

- Risk 1: Ineffective internal complaints handling

- Impact indicator 1: Number of customers

- Impact indicator 2: Number of transactions

- Impact indicator 3: Number of outstanding digital loans

- Impact indicator 4: Value of outstanding digital loans

- Risk 2: Discrimination against women

- Impact indicator 1: Number of female customers

- Risk 1: Ineffective internal complaints handling

Example 5

Policy goal: Expand financial inclusion

- Supervisory objective 1: Expand physical outreach of financial services outlets

- Risk 1: Weak agent network management

- Impact indicator 1: Number of agents

- Impact indicator 2: Number of merchants

- Risk 1: Weak agent network management

- Supervisory objective 2: Reduce the gender gap in financial services usage

- Risk 1: Persistent algorithmic biases against women

- Impact indicator 1: Number of algorithm-enabled products in the market

- Risk 2: Gender gap in mobile phone ownership

- Impact indicator 1: Number of mobile-enabled products

- Impact indicator 2: Number of mobile transactions

- Risk 1: Persistent algorithmic biases against women

Resource for Step 3: Example of a Risk Assessment Methodology for EMIs

Risk-based supervision of nonbank electronic money issuers (EMIs) needs to be commensurate with their risk profile, namely the risks inherent to their activities, and their systemic importance. Risk-based supervision thus relies on a systematized identification of risks and their relative importance within and across EMIs. The adoption of a risk-based approach (RBA) can help supervisors increase or reduce the intensity of supervision of different EMIs over time, in a flexible but structured manner. To take full advantage of an RBA, supervisors should have a process in place to maintain an up-to-date understanding of the risk landscape, and systematically identify and assess the level of risks in individual EMIs on a periodic basis, taking into consideration their inherent risks and the controls applied against them.

Developing a risk assessment process

The risk assessment process plays a great role in shaping the supervisory priorities, the level and duration of supervisory scrutiny, how supervision should be conducted, the appropriate balance among supervisory activities (e.g., between offsite supervision and onsite/remote inspections), and the resources allocated to ensure that the required experience and skillsets are assigned to assess the risks. Risk assessment is not a static process, it should be continuous and dynamic to reflect the changes in risks arising from both the EMI itself and its external environment (e.g., macroeconomic situation, sectoral conditions).

Past supervision activities (e.g., thematic reviews, offsite supervision, onsite/remote inspections) are an essential input to the risk assessment process. During this process, the supervisor should consider the findings, assessments, recommendations and action plans, ratings, remedial actions and sanctions from the previous supervision cycles and reports.

Data analysis and continuous monitoring are also necessary for a proper risk assessment. They help supervisors identify (and compare over time) variations in the risk profiles of EMIs. The ability to collect diverse data from different sources would have a direct impact on the depth of the assessment under each of the inherent risk types considered in the risk assessment methodology and the supervisor’s ability to maintain an up-to-date risk assessment.

If the supervisor recently started to implement an RBA to EMI supervision, they should put together an initial and comprehensive risk assessment that also benefits from any previous assessment of individual EMIs (even if the previous cycle was not risk-based). In a small market, the supervisor of EMIs may be able to cover all EMIs for the risk assessment, and even all relevant risks. But for other markets, this will not be on the table due to limited supervisory resources relative to the number of EMIs.

Assessing EMIs’ inherent risks

Supervisors should first understand the overall risk profile of EMIs as a provider type, which is first determined by regulatory requirements and permitted activities. EMIs are not allowed to intermediate customer funds or to engage in risky operations such as trading and foreign exchange. Banks manage a complex array of intertwined risks and are leveraged (they do not have enough funds to pay back all depositors at once). However, EMIs are typically mandated to always have enough funds to pay back all customers in full. These fund safeguarding requirements aim to protect customers and allow for a lighter supervisory approach. Additionally, regulations often cap e-money transactions and accounts balances to limit certain risks.

However, these requirements don’t make EMIs free of risks. EMIs offer payment services (withdrawals, transfers, and purchases) through a variety of channels, using IT systems, telecommunications, business partnerships, outsourcing arrangements, widely dispersed staff and agents, connection to merchants, and payments infrastructures, such as switches and other payment systems. These elements create operational, market conduct, money laundering and financing of terrorism (ML/FT) risks, which are often the most important for supervisors of EMIs. EMIs may also face other risks such as strategic, liquidity, and legal risks.

Supervisors should then understand that not all EMIs pose the same level of risk. Some EMIs and certain activities in the e-money industry may be considered as potential sources of systemic risk, with substantial or high impact on customers, industry and/or the economy as a whole. And there would be others that do not have systemic importance but still have medium impact. Also, not all activities are equally risky within an EMI.

To assess inherent risks, supervisors should first identify the significant activities of EMIs that pose the greatest risk to the supervisory objectives. The degree of importance of impact indicators would be factored in determining the significant activities and their respective significance level. Many supervisors prefer to also assign quantitative weights to these activities to indicate their level of significance. After determining the significant activities, it is essential to assess the level of key inherent risks posed by each of such activities. Inherent risk is the level of risk that is present in the EMI’s activities without considering its risk mitigation measures and the quality of risk management and internal control practices. It is the probability of a loss due to exposure of the EMI to current or potential future events or changes in its business or macroeconomic situation in the country, which may also lead to potential damage to its customers. The assessment of inherent risk involves a consideration of the probability of the materialization of an event and the potential size of its adverse impact on the EMI’s earnings and overall financial situation. Some supervisors prefer to give numerical ratings to such risks, some others prefer to go with different ratings categorizations (e.g., categories of High, Medium High, Medium, Medium Low, and Low) where each rating should have a specific definition that helps the next supervision team and others in the supervisory authority easily understand it.

Assessing EMIs’ net risks

Finally, the risk assessment process requires supervisors to understand how these inherent risks turn into net risks for each EMI. For this, supervisors need to assess the status and effectiveness of the internal controls, risk management, and governance measures against the inherent risks of the EMI. Supervisors often assign ratings to the quality of risk management, control and governance measures (e.g., strong, acceptable, needs improvement, or weak). Net risks are the risks that remain after all such measures are applied by EMIs to reduce their inherent risks. Supervisors should recognize that no matter how robust an EMI’s board and senior management oversight, internal controls and risk management process are, inherent risks cannot be eliminated, they cannot be zero. Also, supervisors should be able to reflect in their assessment of “net risks” any major concerns they may have about an EMI’s potential risk impact on the financial system.

An EMI with weak risk management and internal controls may not be high-risk if inherent risks arising from its operations and activities are already at a low level. At the same time, an EMI with high level of inherent risks should not be assumed as “high risk” in advance, since it can have appropriate internal controls that are properly applied, so its net risk could be low (however, such EMI – for instance, an EMI with the largest number of customers – will always be high on the supervisor’s radar).

Supervisors in many jurisdictions use risk matrices to summarize the risk profile of a financial services provider. A risk matrix often presents all risks inherent to a type of business—according to the activities. It assigns weights to these activities according to their relative importance to the business type. Based on actual risk assessments of providers, supervisors indicate how well or badly a provider mitigates inherent risks through governance, risk management, and internal controls. This methodology produces a risk rating assigned to each provider, which is comparable across providers. The risk matrix allows for better supervisory planning and use of resources.

However, there is no single risk-based methodology and risk matrix model that would work for all supervisors of EMIs. They often define risks differently and choose different inherent risk types, and respective relative weights for their risk matrices. They also create different risk ratings and trend assessment methods. A risk matrix that is generally designed for banks or other financial services providers (e.g., insurance providers) will not fit the risk profile of EMIs. The risk matrix for EMIs would be significantly simpler than a matrix used for banks because banks usually have a more complex combination of activities, which makes their inherent risk profile more complex.

Setting up DFS Supervision

Internal organization for DFS supervision

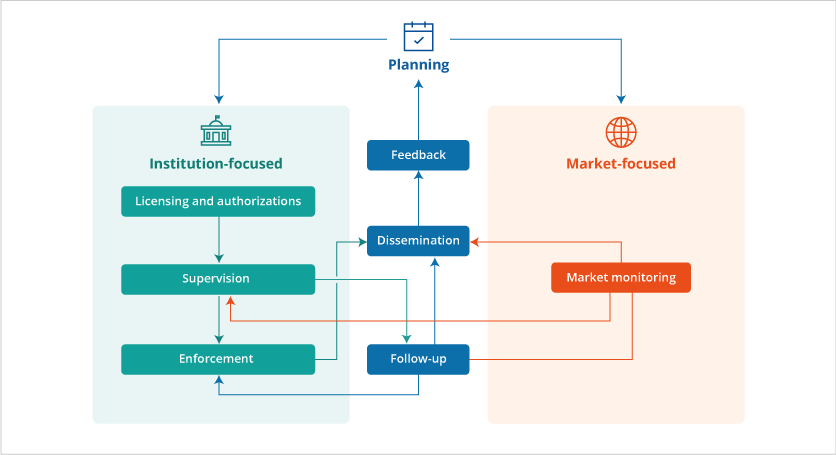

One of the main questions in DSF supervision is how to balance institution-focused and market-focused activities, and the role internal organization can play in achieving such a balance.

The decision about how to organize the different functions and activities involved in DFS supervision depends on various factors such as the adoption, by the supervisory authority, of a matrix organizational structure in which there are specialized teams dedicated to certain core or support functions and which work across the whole organization and would cover DFS providers.

Cross-support units may include teams specialized in certain risks or topics, such as operational and IT risks (e.g., Malaysia, Mexico, Philippines), anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT), market conduct and consumer protection, and cybersecurity (e.g., Monetary Authority of Singapore).

Country Examples

At Central Bank of Jordan, the Oversight and Supervision on National Payment System Department has two separate teams: one responsible for NPS oversight and another for payment providers supervision.

In Mexico, CNBV conducts institution-focused supervision and has a specialized unit responsible for both supervising payment networks (e.g., ATMs and POS networks) and payment service providers, including EMIs and other DFS providers.

The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) is the sole regulatory and supervisory authority for the whole financial sector in Singapore, including all DFS providers, and it is also the central bank. While EMI supervision is handled by the bank supervision department at MAS, the payments department conducts oversight of the whole NPS, including e-money.

The Bank of Ghana created the Fintech and Innovation Office in 2020, with the purpose of supervising DFS providers including EMIs, and all types of fintech companies that may fall under the Payment Systems and Services Act, 2019. The Fintech and Innovation Office reports directly to the Bank of Ghana’s Governor. The Fintech and Innovation Office took over DFS supervisory activities that were previously under the responsibility of the Payment Systems Department (e.g., supervision of EMIs). Currently, the Payment Systems Department oversees market infrastructures such as the Real-time Gross Settlement (RTGS) System and payment services provided by banks. It also approves DFS products offered by banks.

Adapted from CGAP (2023)

Functions and Activities that comprise DFS Supervision

DFS supervision involves market-focused and institution-focused activities. In addition, several functions support core supervisory activities.

Types of supervisory activities

All core and support functions require specific expertise and skills such as those described below. Overall supervisory capacity will also entail technology requirements such as IT infrastructure, data analytics programs, statistical applications, and data visualization tools.

Supervisory Functions and Activities

| Core functions and activities | Expertise | Skills | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Market-focused activities | Market monitoring (including thematic reviews) |

|

|

| Institution-focused activities | Remote/onsite inspections

|

| |

| Support functions and activities | Expertise | Skills | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervisory capacity building | Supervisory planning |

|

|

| Training |

| ||

| Supervisory policy and guidance development | Internal guidance development |

|

|

| Guidance to DFS providers and policy statements | |||

| Regulatory change proposals |

| ||

| Regulatory reporting | Submissions management |

|

|

| Data validation | |||