Overview

There are three ways that the guiding principles could be implemented. They include:

- An overarching law on data protection and privacy.

- Incorporating data protection aspects in existing and related financial sector regulations.

- Code of practice developed by industry association or representative body.

Overarching Laws

Data protection and privacy issues have cross-cutting implications and wide-spread applicability. As a result, several countries are developing overarching data protection and privacy laws which consolidate the legal framework. Additional regulations can incorporate aspects of the DFS landscape. Overarching laws often create and/or empower a supervisory and enforcement entity which is vital for implementation.

Overarching Law with Financial Sector Consultation

The Law on the Protection of Personal Data and Privacy (Data Privacy Law) was passed in 2021. It applies to data controllers, processors, or third parties that are established or ordinarily residing in Rwanda and processing personal data while in Rwanda. It also applies to those that are not established or resided in Rwanda, but process personal data of data subjects located in Rwanda. Implementation and supervisory powers reside with the National Cyber Security Authority ('NCSA').

Rwanda’s Data Privacy Law was enacted after a comprehensive consultation process. During the consultation process, multiple additions and revisions were received from private companies in Rwanda. The most feedback and corrections received were from the financial sector, which widely deals with citizens' sensitive personal data.

The Personal Data Protection Law (PDPL) was enacted in 2011. The Regulation of the PDLP (Regulation) was published in 2013 to develop, clarify and expand on the requirements of the PDPL and set forth specific rules, terms and provisions regarding data protection. Together, the PDLP and its Regulation form the overarching legal and regulatory framework.

In 2021, the Superintendency of Banking, Insurance and Pension Funds (‘SBS’) approved the Regulation on Management of Information Security and Cybersecurity. This additional regulation updated requirements for information security in line of with international standards and best practices. In particular, the Regulation provided for a regulatory framework for the information security management system of supervised entities, laying down requirements with respect to the implementation of authentication in digital channels, outsourcing of data processing services including cloud processing, as well as updating and incorporating proportionate information security requirements.

Similarly, the Superintendence of the Securities Market ('SMV') enacted Regulations for Crowdfunding and Crowdlending Activities and their Administration in 2021. This regulation reiterated the minimum data protection measures as established in the PDPL and Regulation. Furthermore, it focused on risk mitigation mechanisms that allow both investors and project promoters to know all relevant information while maintaining strict guidelines to prevent personal information leaks for either party.

Overarching Law and a DFS Policy

The primary legislation which protects data privacy is the Data Protection Act, 2012 ('the Data Protection Act'). The purpose of the Data Protection Act is to establish a Data Protection Commission ('DPC'), to protect individuals' privacy and personal data by regulating the processing of personal information, to outline the process to obtain, hold, use, or disclose personal information, defining the rights of data subjects, prohibited conducts of processing, third country processing of data relating to data subjects covered by the Act, third country data subject processing in Ghana.

Separately in May 2020, Ghana launched a four-year (2020 -2023) DFS Policy. It is designed to serve as a blueprint for how Ghana can leverage digital finance to achieve its financial inclusion goals, complementing Ghana’s National Financial Inclusion and Development Strategy. Data privacy and data security were noted as particularly important in the DFS context. The Policy included proposals to strengthen the data protection and policy legal framework to

- Build institutional capacity of the DPC to complete the data controller registration process under the Data Protection Act.

- Creating technical capacity to deal with data specificities in the DFS ecosystem.

- Increase cooperation through an MOU between the DPC, financial sector regulators and the National Communications Authority.

- Evaluate regulatory gaps with respect to use of alternative data in the financial sector.

Overarching Law with Financial Sector Provisions

Brazil’s General Data Protection Law (LGPD) is designed to unify existing laws to regulate processing of personal data of individuals. The LGPD was influenced by the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and has also expanded its coverage in some areas from the GDPR’s parameters. It has a much simpler format and there are key differences including lower monetary penalties, shorter timeframes to comply with data subject access requests, and a specific legal basis for credit protection.

Article 7 outlines the legal bases or circumstances under which data processing may be carried out. One of the legal bases is for the protection of credit ratings. Having the protection of credit as a legal basis for the processing of data is a substantial departure from the GDPR.

Another financial sector provision relates to automated processing, however, this is aligned with the GDPR. Article 20 states that the data subject has the right to request for the review of decisions made solely based on automated processing of personal data affecting her/his interests, including decisions intended to define her/his personal, professional, consumer and credit profile, or aspects of her/his personality.

Provisions in Financial Sector Regulations

In the absence of a law, there are risks in allowing providers to start operating. Some risks could be mitigated by designing a system that incorporates privacy principles. Conversely, waiting to act until the law is in place could significantly delay the development of enabling institutions and systems. As an alternate (or interim) step, some financial sector policymakers and regulators are incorporating data protection and privacy aspects in financial sector laws and regulations.

India’s draft law, the Personal Data Protection Bill was pending in Parliament since 2019 before being withdrawn in August 2022. It was reintroduced as the Digital Personal Data Protection Act in November 2022. In an adjusted approach, the government potentially intends to have specific legislation for different aspects of the digital technology landscape rather than an omnibus legislation.

At the same time India’s investments in digital financial infrastructure—known as “India Stack”—have sped up the large-scale digitization of people’s financial lives. As more and more people begin to conduct transactions online, questions have emerged about how to provide millions of customers adequate data protection and privacy while allowing their data to flow throughout the financial system.

India’s interim solution has been to introduce adequate financial sector regulations which can enable growth even before an overarching law is in effect.

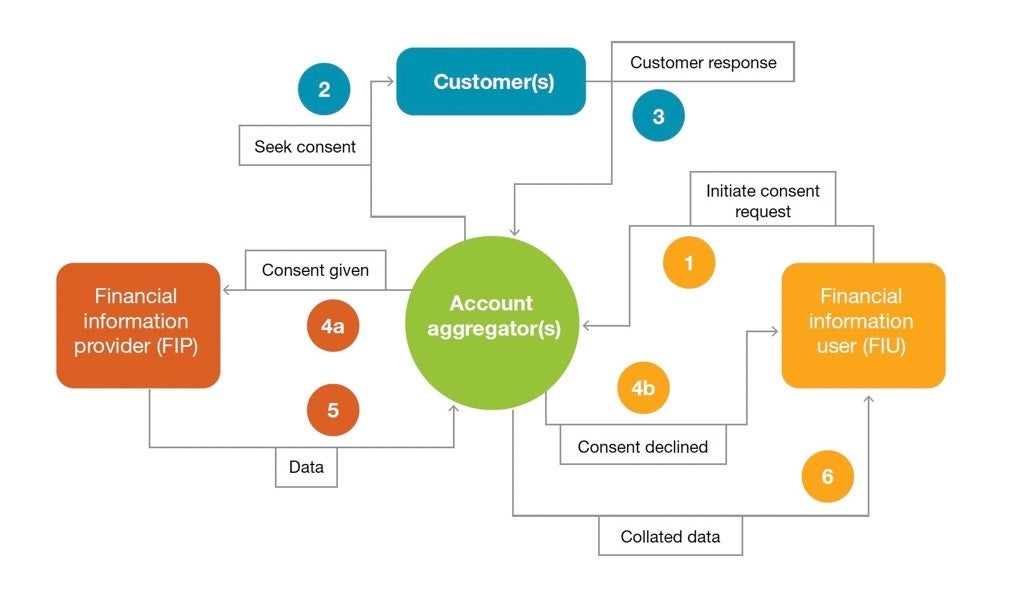

One of the solutions is the creation and regulation of account aggregators (AAs) by Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to simplify the consent process for customers. AAs have been designed to sit between FIPs and FIUs to facilitate data exchange more transparently. Despite their name, AAs are barred from seeing, storing, analyzing, or using customer data. As trusted, impartial intermediaries, they simply manage consent and serve as the pipes through which data flow among FSPs. When a customer gives consent to a provider via the AA, the AA fetches the relevant information from the customer’s financial accounts and sends it via secure channels to the requesting institution.

Account Aggregator Ecosystem

The information flows as follows:

- FIU initiates a request to AA for specific data (with predefined, standardized parameters) for a specific purpose

- AA sends the customer a message to obtain her consent to share the requested data for the purpose specified in the request

- Customer examines the request and chooses to either accept or reject the data request

- AA processes the customer’s response:

- If customer consents to the request, AA forwards a request to fetch the data from FIPs

- If consent is denied, AA informs FIU that the customer has declined the request

- FIPs examine the request, obtain the data from their systems, encrypt the data, and send the data to AA

- AA can collate data into one package if there are several FIP sources for a single request and forward the package to the requesting FIU. AAs cannot view, store, modify, use, or analyze customer data. This makes AAs materially different from credit bureaus and distributed sales agencies (DSAs). The AA is a “data blind” messenger

Note that DSAs are third parties that help banks collect physical records such as bank statements. They are used by financial services providers to assess risk and eligibility. They present a risk of data theft. Credit bureaus are different in that they use data to create scores based on analytics.

Among other financial sector regulations, India has required credit card issuers and payment processors to store data on local transactions inside the country. In addition to its demand to store data locally, RBI ordered all companies to purge debit and credit card details beginning in 2022 to protect customers from being charged against their will. Overall, India has also been able to use the reform momentum from India Stack to build out a Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture (DEPA) as an ecosystem-wide, joint public-private effort for a new and improved data governance approach.

Pakistan’s Personal Data Protection Bill has been in draft stage since 2018. The draft has been amended several times but has not gotten close to approval.

In the absence of an overarching law, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) has been using alternate legislation and regulations to reiterate the importance of data protection and privacy in the financial sector.

Section 33A of the Banking Companies Ordinance (1962) requires that financial institutions shall not divulge any information relating to the affairs of its customers except in circumstances in which it is, in accordance with law, practice and usage customary among bankers, necessary or appropriate for a bank to divulge such information.

Section 70 of the Payment Systems and Electronic Fund Transfers Act (2007) provides that a financial institution or any other authorised party must not divulge any information relating to electronic fund transfers, affairs, or accounts of its consumers.

Elements of confidentiality of consumers' data in storage, transmission, and processing are covered in regulations such as Regulations for Payment Card Security and Regulations for the Security of Internet Banking, among others.

There are two key challenges with this approach.

First, in the absence of an overarching law, there are limitations to how effective supervision and enforcement (including the ability to impose penalties for non-compliance). For example, in 2018, the SBP issued a Circular (BPRD Circular No. 08 of 2018) which observed that centralization of core banking systems of banks made customers’ data accessible across each bank and there was limited mitigation of the risk that only authorized officials were accessing confidential data for specified purposes.

Second, this approach also raises concerns about the mandate of the financial sector regulator in some cases. For example, in 2004 SBP issued a directive that called for the collection, without any sustainable juridical criteria, personal information of individuals who earned at least PKR 10,000 in interest. The directive was struck down by the High Court on the grounds that taking of private information without any allegation of wrongdoing of ordinary people is an extraordinary invasion of this fundamental right of privacy. Subsequently, in 2019, the tax authority approached SBP to get access to data of individuals with PKR 500,000 account balances with a view to bringing them into the tax net. On this occasion, SBP declined and stated that the existing legal framework provides constraints on procuring and sharing of privilege/confidential information relating to customers of the banking sector.

Codes of Practice

In some cases, industry associations have also developed codes of practice to ensure that the market proactive manages risks and benefits from data-led growth. Codes of practice can be mandatory if established under an overarching law as a complementary enforcement mechanism, or they can be voluntary if developed by the market or an industry association.

Mandatory Code of Practice

Malaysia’s Personal Data Protection Act makes provision for the registration of ‘data user forums’ that may then prepare a mandatory code of practice on their own initiative or at the request of the Personal Data Protection Commissioner (Part II, Division 3). The code will be registered if the Commissioner is satisfied that it is consistent with the Act and due consideration has been given to the purposes of processing data by relevant data users, views of data subjects and the relevant regulatory authority (such as Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM)), and the code overall offers an adequate level of protection. The penalty for a breach of the Code is a fine not exceeding 100,000 ringgit (approx. US$2,42561) and/or imprisonment up to 1 year.

The Personal Data Protection Code of Practice for the Banking and Financial Sector (2017) (BFS Code) is registered under the above provisions. The Code applies to all licensed banks and financial institutions and was developed by the Association of Banks in Malaysia. The Code summarizes relevant provisions of the Act, the related regulations and BNM’s Product Transparency and Disclosure Guidelines and provides sector-specific examples of how they can be interpreted in practice. Emphasis is placed on explaining the definitions of personal, sensitive, and pre-existing data and rules concerning direct marketing and cross-selling, contacting the data subject and the transfer abroad of data. Templates are also provided for a Privacy Notice, a Data Access Request Form, and a Data Correction Request Form.

Voluntary Code of Practice

The Global Financial Markets Association (GFMA) released its Financial Data Handling Principles for Banks and Non-Banks in 2019 as a voluntary set of principles drawn from international best practices. The principles are based on both the U.S. NIST Cybersecurity Framework and the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). GFMA brings together three of the world’s leading financial trade associations to address the increasingly important global regulatory agenda and to promote coordinated advocacy efforts. The Association for Financial Markets in Europe (AFME) in London and Brussels, the Asia Securities Industry & Financial Markets Association (ASIFMA) in Hong Kong and the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA) in New York and Washington are, respectively, the European, Asian and North American members of GFMA.

The principles recommend that firms should:

- Limit the collection, processing and use of personal data to that which is necessary to accomplish a lawful purpose.

- Provide a reasonable means for data subjects to check and correct the accuracy of personal data held about them.

- Limit access to personal data to users on a need to know basis and monitor such access on a periodic basis.

- Protect against unauthorized or unlawful access to, or removal of, personal data using a risk-based approach with reasonable technical and procedural measures.

- Use a risk-based approach to employ appropriate safeguards, such as encryption, when transferring data.

- To the extent reasonably feasible, securely eradicate, dispose of, or destroy personal data without delay when there is no longer a valid business, legal or regulatory purpose to retain it.

- Only provide personal data to external entities with data protection policies and procedures consistent with these principles or where required by law.

- Implement a monitoring programme designed to identify and resolve data security issues, gaps or weaknesses; and remediate any issues found.

- After establishing that a loss or compromise of personal data has occurred, promptly notify regulators and individuals who have been substantially harmed.

- Work together with other financial institutions and regulators in exchanging views and intelligence with a view to continually improving data security.

Policy and Regulatory Tools in Practice

Policymakers and regulators for DFS may consider the following practical actions which can support all the implementation approaches mentioned. In many cases, these are actions during the interim period before there is a comprehensive data protection and privacy law in place.

Cover both public and private sectors, including products, providers (traditional and FinTech based), delivery channels, customer segments, types of data used and analytic tools.

Develop methodology for assessing privacy risks in DFS business models from e.g., information sources, information sensitivity, use cases and systems interconnectivity.

Consider especially, the needs of vulnerable groups.

Consider financial inclusion objectives.

Include public, private, and civil society representatives and ensure both traditional and FinTech entities are consulted.

Privacy by design.

Default governance and resource arrangements.

Transparent information for data subjects about data processing.

Effective and informed consent.

Rights to access and correction, and to object to processing.

Recourse for data subjects with complaints.

Risk-based criteria could cover:

- Volume and sensitivity of data processed.

- Number of data subjects.

- Turnover.

- Risk of harm to data subjects e.g., on basis of discrimination or bias.

- Use of new technologies for data processing, such as automated processing and profiling.

Rules could cover:

- Needs for registration.

- Data Privacy Officers.

- Data privacy impact assessments.

- Breach reporting to regulators and to data subjects.

- Independent assessments of compliance.

Have specific focus on the diverse needs of vulnerable groups, education on data privacy risks with DFS, and related rights and responsibilities.

Key ministries and regulators, FinTech and traditional DFS data controllers and consumer associations.