Implementation of Supervision Approach

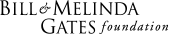

Supervisory Cycle

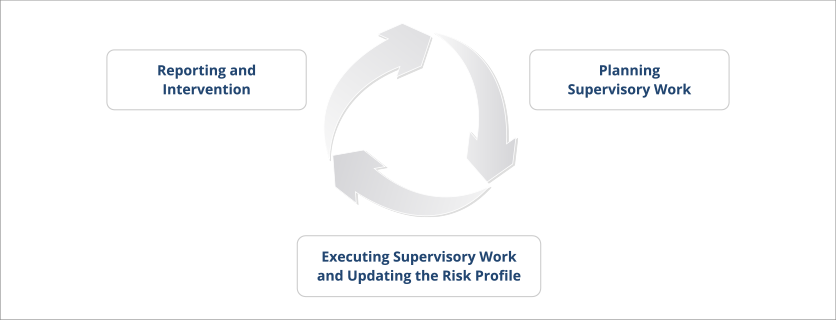

DFS supervision is in an ongoing cycle of assessing risks, taking supervisory measures, and following up on them, providing feedback to adjust the supervisory approach and regulations, and the planning for the next year. The supervisory cycle illustrated below may be documented in the form of a supervisory framework.

Implementing the Supervisory Cycle

Country Examples

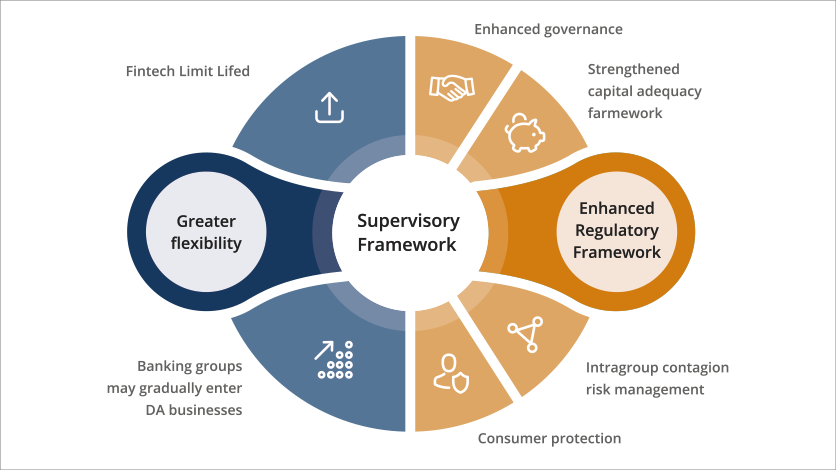

Based on the supervisory approach chosen by the Bank of Thailand (BOT), the BOT has designed a supervisory framework that finds a balance between fostering innovation and having proper risk management, while also taking into account the dynamic nature of the business.

In Canada, the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) uses a defined process to guide its institution-specific supervisory work: the first step is planning supervisory work; the second is executing supervisory work and updating the risk profile; and the third is reporting and intervention.

Implementation of Supervision Approach

Develop a Risk Assessment Methodology

Risk-based supervision requires systematic risk assessments of individual DFS providers based on a standard methodology. A risk assessment methodology is a guide for supervisors to measure each provider’s risk, with the purpose of prioritizing supervisory efforts. In its text form, the methodology looks like a supervision manual, with instructions for analytical procedures.

An example of prioritization based on impact and net risk

For those not fully versed in RBS, using a single risk score to compare and prioritize DFS providers after prioritizing them by impact indicators can be a confusing task. Which prioritization is more important? Does the risk score substitute for the impact indicators? What is the relationship between risk weights and impact indicators?

The following hypothetical example uses two DFS providers to clarify these questions. The table shows an impact indicator (number of accounts), the assessment of two risks (one with high weight in the risk-scoring methodology and one with low), and final risk score (net risk).

Which DFS provider should the supervisor prioritize? The short answer is Provider 1 because the potential impact of its risks is higher. It will, therefore, always be a higher priority provider. A provider with a much lower impact indicator may not even be subject to a full risk assessment.

Assuming a risk assessment was conducted on Provider 2, findings could include that Provider 2 has poorer internal controls, risk management, or governance; is scored at a higher risk level (with an upward trend) than Provider 1; and that particular concern exists in the important area of risk (fund safeguarding). Still, Provider 2 is much smaller than Provider 1. The supervisor’s decision on what to include in the supervision plan for the next year will depend on specific circumstances, such as staff availability. However, by using the impact indicator and assessing risks in the two providers, the supervisor can make a few decisions to optimize staff time. For instance, she may decide to include in the annual supervision plan:

- Remote follow up on Provider 1’s credit risk issue

- Ongoing remote monitoring of a set of key indicators for both providers (e.g., transaction levels, account numbers, total e-money issued, etc.)

- A special onsite inspection to follow up on improvements to Provider 2’s fund safeguarding practices, as agreed upon in the time-bound action plan the provider delivered

This example shows that RBS methodology is not a zero-sum game. It is not about “this or that” provider. It is a method to identify priority activities to be performed based on the knowledge of the risks of different providers. Designing a risk assessment methodology, including assigning relative levels of importance to different risks (risk weights) and identifying level of importance of their risk mitigants (e.g., internal controls), helps supervisors calibrate the scope and type of supervisory activities to perform. They may otherwise be tempted to plan full scope inspections (assessments) that cover all risk areas every year—at least on large providers.

A key takeaway from this example is what the supervisor’s annual plan does not include. She will not repeat a full risk assessment on both providers. That is one of the most important contributions of the RBS methodology: there is no need to perform a full scope risk assessment on all providers, let alone every year.

Defining a Risk matrix

The objective of conducting a risk assessment is to estimate the net risk of a particular DFS provider. The risk assessment will evaluate the internal controls, risk management, and governance measures put in place by the provider to mitigate the risks inherent to its business and broader market risks that may exist. Then, by comparing the net risk of different providers, supervisors can fine tune their prioritization of providers, which started with the analysis of impact indicators. Moreover, the assessment will give granular knowledge of how each provider deals with each risk, so supervisors can prioritize the most problematic risk areas, and adapt the scope of such subsequent risk assessments accordingly, in future assessments.

Approach to Net (or Residual) Risk Assessments

| Aggregate Quality of Risk Management for a Significant DFS Activity | Level of Inherent Risk | |||

| Low | Moderate | Above Average | High | |

| Net Risk Assessment | ||||

| Strong | Low | Low | Moderate | Above Average |

| Acceptable | Low | Moderate | Above Average | High |

| Needs Improvement | Moderate | Above Average | High | High |

| Weak | Above Average | High | High | High |

Up to this stage, supervisors have identified impact indicators, which are indicators of inherent risk: DFS providers undertaking similar activities will have a similar set of risks that are inherent to that activity. For instance, cybersecurity risk is faced by virtually all DFS providers, so it can be considered a risk that is inherent to the DFS business. All providers will have this risk.

However, the actual level of risk faced by each DFS provider will vary according to each provider’s risk management and mitigation practices. This "actual level” is known as net (or residual) risk. The risk assessment methodology is the main guide to help DFS supervisors estimate the net risk of each provider. It could be, for instance, that a provider previously classified as high risk for having the largest customer base. But, from a cybersecurity risk perspective, this provider may have the best risk mitigation strategies among all providers, so it would be ranked lower (with respect to cybersecurity risk).

The first step in designing a risk assessment methodology is to identify all relevant risks (also known as risk factors, risk components, or risk categories). For instance, a risk in nonbank e-money issuers (EMIs) is the risk of ineffective fund safeguarding. In bank prudential supervision, commonly used risks include credit risk, liquidity risk, and capital. For each risk, the methodology will explain how that risk is to be evaluated and which specific indicators and risk mitigants are to be covered in the assessment. For the EMI example, a mitigant for the fund safeguarding risk could be effective reconciliation between the total e-money issued and the funds set aside in float (trust) accounts.

The elements of the risk assessment methodology can be summarized in a risk matrix, like the example below:

Template for Risk Matrix

| DFS Activity (Business line, product, or combination) | Activity 1 (e.g. e-money wallet) | Activity 2 (e.g. cash-in/cash-out transaction) | Activity 3 (e.g. mobile insurance) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significance | ||||

| Inherent Risks | Credit | High Above Average Moderate Low | High Above Average Moderate Low | High Above Average Moderate Low |

| Market | High Above Average Moderate Low | High Above Average Moderate Low | High Above Average Moderate Low | |

| Insurance | High Above Average Moderate Low | High Above Average Moderate Low | High Above Average Moderate Low | |

| Operational | High Above Average Moderate Low | High Above Average Moderate Low | High Above Average Moderate Low | |

| Regulatory | High Above Average Moderate Low | High Above Average Moderate Low | High Above Average Moderate Low | |

| Strategic | High Above Average Moderate Low | High Above Average Moderate Low | High Above Average Moderate Low | |

| Others | High Above Average Moderate Low | High Above Average Moderate Low | High Above Average Moderate Low | |

| Quality of Risk Management | Operational management | Strong Acceptable Needs Improvement Weak | Strong Acceptable Needs Improvement Weak | Strong Acceptable Needs Improvement Weak |

| Financial risk management | Strong Acceptable Needs Improvement Weak | Strong Acceptable Needs Improvement Weak | Strong Acceptable Needs Improvement Weak | |

| Internal controls | Strong Acceptable Needs Improvement Weak | Strong Acceptable Needs Improvement Weak | Strong Acceptable Needs Improvement Weak | |

| Governance | Strong Acceptable Needs Improvement Weak | Strong Acceptable Needs Improvement Weak | Strong Acceptable Needs Improvement Weak | |

| Compliance | Strong Acceptable Needs Improvement Weak | Strong Acceptable Needs Improvement Weak | Strong Acceptable Needs Improvement Weak | |

| Others | Strong Acceptable Needs Improvement Weak | Strong Acceptable Needs Improvement Weak | Strong Acceptable Needs Improvement Weak | |

| Net risk | High Above Average Moderate Low | High Above Average Moderate Low | High Above Average Moderate Low | |

| Risk direction | Increasing Constant Decreasing | Increasing Constant Decreasing | Increasing Constant Decreasing | |

The matrix is a visual representation comprising all types of inherent risk of an individual DFS provider. In the matrix, “DFS Activity” can be a business line, a type of DFS product, or a combination of both. This is often referred to as “significant activity”. Less complex DFS providers may not require the identification of different significant activities. Each type of inherent risk, for each significant activity, will be assigned a degree of significance – i.e., a weight – that will impact the total inherent risk of the DFS provider.

The use of weights for risks and significant activities within each provider allows supervisors, after evaluation of the quality of a provider’s internal controls, risk management process and governance, calculate the net risk, which is the sum of all weighted risks.

The net risk is represented by a rate (or score), i.e., a single number or letter, or a short expression, chosen from a pre-determined rating (or scoring) scale (e.g., risk levels 1 to 4, or risk levels Low to High). With the rate at hand, supervisors can more easily compare providers, in a consistent manner. Additionally, DFS supervisors should make a judgement about the direction of risk for the DFS provider, that is, whether the expectation is for the net risk to increase, maintain stable, or reduce.

A risk assessment methodology and its risk matrix can be developed for virtually any type of DFS provider. This is the same idea applied to the more well-known risk matrices for prudential banking supervision. However, the methodology and risk matrix for most non-bank DFS providers will be much simpler than those used for banks, because banks perform a broader range of activities, which makes their inherent risk profile and the assessment of their net risk much more complex.

The risk matrix above may be used in conjunction with analysis of capital, asset quality, management, earnings, liquidity, and sensitivity to market risk. The composite risk rating derived will provide a basis to prioritize monitoring and intervention activities within a supervision plan. The risk assessment methodology must describe, in a summarized manner, what each level or rate of the rating scale would look like in practice.

Implementation of Supervision Approach

Supervision plan

Supervisors are rarely able to continuously assess, via inspections, all risks covered in the initial risk assessment. As a result, subsequent supervisory activities – e.g., inspections, thematic reviews – will need to be decided upon an evaluation of which identified risks in which DFS providers will be in the next year’s operational plan. Having a detailed and well substantiated plan will help DFS supervisors manage ad hoc requests from the top management or the government. It is advisable to always leave some staff time free in the annual plan to accommodate unexpected activities and projects related to such requests.

Implementation of Supervision Approach

Using a mix of supervisory tools

There is a diverse range of supervisory activities that DFS supervisors carry out. For each activity, there is a range of offsite and onsite tools that can be deployed.

Mixing supervisory tools is important for effective RBS. The combination of the tools should be based on the objectives pursued, the existing capacity to deploy them, and the need to use resources in a proportionate manner, according to the risk profile of DFS providers. For instance, institution-focused supervision should not only rely on onsite inspections, but also offsite (remote) inspections, and tools such as whistleblower investigations and mystery shopping. Follow-up tools include requiring course correction by DFS providers, providing guidance to the market, referring cases to a criminal authority, and proposing regulatory change. Enforcement tools include fines, product withdrawal, suspension of operations, and requirement to increase capital.

Tools for dissemination include publishing statistical reports, reports on supervisory activities and summary of enforcement actions. Licensing is also important to DFS supervision as, in addition to keeping unqualified applicants out of the market, it provides a wealth of information about DFS providers. In this context, licensing includes a range of authorizations and the licensing of new entities.

Moreover, market-focused activities (e.g., thematic reviews and market monitoring) also feed into institution-focused supervision, and vice-versa. Once supervisors have an initial understanding of the risk profile of each relevant DFS provider, they can decide on the best combination of tools and techniques.

Most supervisors tend to start DFS supervision with a focus on providers (e.g., making an annual plan of onsite inspections), rather than on market-focused activities. One reason, particularly in emerging market developing economies, may be the low quality of data collected on the DFS market, and the tendency of supervisory authorities to prioritize onsite inspections.

Market-focused (market monitoring) activities are indispensable for effective risk-based DFS supervision. Improving it – by improving data collection and data analytics – should be a priority for DFS supervisors. Market monitoring tools¬ include analysis of regulatory returns, social media monitoring, customer interviews and survey, mystery shopping, and thematic reviews, which can use a combination of the previous tools to investigate in greater depth on one or a limited number of topics (e.g., fund safeguarding) across several DFS providers.

Implementation of Supervision Approach

Offsite Supervision

Ongoing offsite supervision includes offsite analysis on both the whole market and specific institutions. It plays a central role in risk-based supervision, as it helps identifying DFS providers and risks that warrant greater supervisory attention and resources during institution-focused inspection work (onsite or remote inspections).

Offsite analyses as part of ongoing monitoring or surveillance. In many countries, ongoing (repeated, periodic) analyses are known as offsite supervision or offsite surveillance. It could but does not need to be in the hands of a dedicated team. This type of monitoring can be split into two focus areas: (i) market-focused monitoring and (ii) institution-focused monitoring. The two complementary activities feed each other. For instance, a set of indicators originally produced for institution-focused monitoring may also be useful in market-focused monitoring.

| Market-focused monitoring | Institution-focused monitoring |

|---|---|

| Analyses that look at the whole market to identify and measure risks and market trends across all DFS providers and peer groups of DFS providers. Examples: monitoring for consumer protection purposes by looking at indicators such as volume and nature of complaints; monitoring of growth trends in the e-money industry by looking at indicators such as total e-money issued compared to total retail deposits. | Analyses that focus on key aspects of individual DFS providers. Examples: monitoring compliance with specific regulatory requirements such as the equivalence between total e-money issued and the balance in float accounts; monitoring financial performance of DFS providers by looking at indicators such as profitability and operational efficiency. |

Offsite analyses to support inspections and thematic reviews. Supervisors should make a significant effort offsite prior to departing for an onsite inspection or before they start a remote inspection. The better the offsite inspection preparations, which are institution-focused by nature, the more efficient and effective the onsite or remote inspection. Thematic reviews may also partially or entirely rely on offsite analyses.

Note that there are differences between offsite institution-focused monitoring and offsite analyses to support an inspection. The main differences are in the data and skills needed:

- Differences in the data. Monitoring primarily uses data that are regularly collected through regulatory reports and other regular sources (e.g., data reported by other departments or agencies, collected from social media and websites of DFS providers). Offsite analyses to support inspections use the same regularly collected data complemented by additional information, for example:

- Information requested directly from the DFS provider (e.g., operations manual, business continuity plan, internal audit reports)

- Information collected internally by the DFS supervision department and other departments (e.g., licensing data, previous inspection reports, follow-ups, communications with the DFS provider)

- Information collected externally, such as from other authorities (e.g., ombuds, competition authority, foreign authorities)

- Differences in skills. Expertise and skills also differ between the two types of institution-focused offsite work. Those performing offsite analysis to support inspections often need to engage directly with providers. This requires good communication and persuasion skills in addition to the self-confidence supervisors involved with inspections ideally possess. Monitoring requires data management and analytical skills that may be less important for those performing inspections.

Ongoing offsite monitoring

DFS supervisors should ensure that ongoing monitoring – both market- and institution-focused – is comprehensive and high quality, to fully support the annual supervisory planning and timely adjustments. The aspects below may be considered.

Questionnaire to Assess Quality of Offsite Monitoring

| 1. Periodically assess the quality of offsite monitoring: |

| a. Does ongoing monitoring include both market- and institution-focused monitoring? |

| b. Is ongoing monitoring based on a written framework that describes the objectives, monitoring strategy, the indicators under monitoring, the content and audience of periodic reports (e.g., ongoing, quarterly, and yearly monitoring reports), and staff responsibilities? |

| c. Are the number and the expertise of staff conducting offsite supervision adequate? |

| d. Is the organizational arrangement adequate to support effective offsite monitoring? |

| e. Are the periodic monitoring reports high quality and used to shape the annual supervision plan, and the scope and depth of inspections and thematic reviews? |

| f. Is coordination between departments adequate |

| 2. Periodically assess the data used in ongoing monitoring: |

| a. Is the set of indicators used by ongoing monitoring sufficient and high-quality (accurate, timely, comprehensive)? |

| b. Are shortcomings in monitoring reports due to low data quality, or due to weaknesses in the data analytics and visualization? |

| c. If the shortcomings are related to data analytics and visualization, are the analytics and visualization tools adequate, or is the problem related to expertise or guidance? Or both? What are the solutions? Invest in new software? Invest in training? Hire new staff with expertise on data science, data engineering, statistics, machine learning? |

Implementation of Supervision Approach

Making DFS Supervision more Data-driven

Making DFS supervision more data-driven implies that the supervision function harnessed the power of data and technology to strengthen ongoing market monitoring and other supervisory activities. The following steps provide guidance on becoming more data-driven.

Step 1. Identify data quality shortcomings

Supervisors looking to assure they have the quality and quantity of data they need may ask the following questions: Which data are needed? How frequently? In what format and at what level of granularity? How does that compare with existing data? What are the shortcomings of the existing data?

Current data could have many types of shortcomings including gaps, duplication, inaccuracy, inconsistency, and delays (e.g. time-to-report or period between cut-off date and actual reporting date). Supervisors need to identify the root causes of shortcomings prior to finding solutions, for example, (e.g., buying new software or data warehouse) prior to identifying the causes.

Step 2. Assess quality of data collection mechanisms

Many underlying causes for weaknesses in supervisory data are related to the mechanisms supervisors use to collect the data and those DFS providers use to report data in the required formats. An evaluation of the end-to-end process of regulatory reporting may be necessary.

- Design and imposition of reporting requirements ((including data dictionaries and taxonomies) to ensure a high level of standardization and, hence, comparability.

- Data aggregation, validation, and reporting processes at DFS providers.

- Interface for data transfer between a DFS provider and the supervisor, such as a file transfer system, email, or application programming interface (API).

- Supervisor’s validation of regulatory reporting data submitted by DFS providers, in addition to the validation checks DFS providers conduct before remitting data.

- Supervisor’s management of regulatory reporting submissions by DFS providers, particularly when performed manually (e.g., controlling the timely submission of a large number of reports using spreadsheets).

- Data storage and retrieval methods used by the supervisor.

Step 3. Assess level of data granularity

One key decision supervisors need to make when considering improvements to their data relates to level of data granularity. Granular data are closer to the raw business data DFS providers produce as part of their operations on an ongoing basis. The standards (scope, format, and definitions) of such raw data vary widely across providers according to their respective information systems. Supervisors cannot readily use raw data to compare providers. Data need to be standardized first, that is, the raw data need to be “transformed” into common standards set by the supervisor. The level of standardization detail depend on whether the supervisor wants to collect granular or aggregate data.

Example of reporting an aggregated indicator

Supervisors commonly collect the aggregated indicator that encompasses total number of transactions by different types of DFS providers (e.g., EMIs). The most granular version of the indicator would instead collect the whole transaction database for a certain period, including every transaction, with all of its attributes determined by the information system each DFS provider uses (e.g., client number; transaction type, date, time, amount, and location). When reporting the indicator “total number/value of transactions,” the DFS provider must sum up all transactions in the system and report the aggregated result to the supervisor.

Aggregation is often automated or semi-automated because DFS providers configure their systems to run the necessary calculations to arrive at the required indicator. Full automation is not always possible, particularly when data need to be collected and aggregated from different information systems, and even more so when dealing with legacy systems that use outdated infrastructure and data management architecture.

Step 4. Improve data collection

Supervisors may consider investing in better data collection mechanisms that allow high quality granular data and timely reporting. These mechanisms could be based on technology solutions that expedite the shift away from traditional reporting templates that need to be filled out by DFS providers and toward greater automation. The need for automation is not one-sided, as both the supervisor and DFS providers need to automate procedures on their end. Even if the supervisor installs an excellent interface for data transfer, validation, storage, and retrieval, it will still produce low-quality data if DFS providers continue to use manual processes to gather, transform, and validate data. This approach to data collection is called “data pull.” However, it does not automatically lead to higher data quality in the absence of excellent standardization and validation.

While many solutions have been used to automate reporting in banking supervision over the past decades, newer types of supervisory technology (suptech) are creating opportunities for supervisors to significantly improve data collection without the need to make the prohibitively expensive investments previously required.

Step 5. Improve data analytics

Supervisors need adequate capacity to take full advantage of the data collected. If data collection mechanisms shift toward larger volumes of frequent granular data, the need for analytical capacity increases and new skills and more staff may be required. Suptech can offer value for supervisors in improving data analytics but it does not substitute for the need to invest in analytical skills and expertise. Use cases for suptech in data analytics include:

- Automated compliance checks with certain regulatory requirements like capital requirements, transaction thresholds, and fund safeguarding requirements

- Automated search and preliminary analysis of information publicly available on the internet (web scraping and web crawling)

- Augmented analytical capacity with the use of technologies such as network analysis, topic modeling, and pattern recognition

- Better visualization of analyses of individual DFS providers or the entire DFS market

Some financial authorities have launched initiatives to explore suptech to improve data analytics. For example, De Nederlandsche Bank has a dedicated team to foster the development and use of suptech by supervisory and economic departments. The European Central Bank (ECB) created a SupTech Hub to explore suptech’s potential.

Large data sets and the combination of different data types, sources, and formats to support supervisory findings and decisions require advanced analytics and specialized skills, but not every supervisor needs these skills, particularly in the early stages of DFS supervision. Supervisors must evaluate the required skill set and technology that best supports their objectives, the characteristics of the market, and the data sets at hand.

Country Examples

Reporting Systems

The European Banking Authority (EBA), which establishes a common, pan-European supervisory reporting framework for national (country-level) and European authorities, is currently working towards a more efficient and proportionate supervisory reporting, taking into consideration the need to improve data quality, the compliance costs imposed on reporting institutions, the proportionality of all reporting requirements, and the potential solutions to the shortcomings of the current data collection mechanisms

The EBA has studied the compliance costs and practical challenges faced by reporting institutions with the current data collection mechanisms, putting forward 25 recommendations organized in the following areas:

- Changes to the development process for the EBA reporting framework.

- Changes to the design of EBA supervisory reporting requirements and reporting content.

- Coordination and integration of data requests and reporting requirements

- Changes to the reporting process, including the wider use of technology

In tandem, the EBA has conducted a viability study to implement a new mechanism to integrate the EBA’s systems with the systems of reporting institutions based on clearly stated objectives and principles (e.g., “report-once principle”, or the principle to minimize multiple reporting of the same data). Among other expected results, the new system would reduce the overall scope of reporting requirements, introduce a higher level of granularity and automation in reporting, and integrate all data needs of different EBA departments (e.g., prudential supervision, statistics for monetary policy, and data needed for resolution of regulated institutions). The next steps in implementing the envisioned reforms are:

- Defining a common data dictionary for prudential, statistical and resolution data.

- Further exploring the possibility of increasing granularity or reporting requirements.

- Investigating the need for a common solution for reporting institutions’ compliance process.

- Further investigating the desired target scenario based on a cost-benefit assessment.

- Setting up strong governance arrangements.

- Providing an estimate of costs and resources needed.

In a dedicated online page, the EBA provides extensive guidance to reporting institutions with its Single Rulebook Q&A on Supervisory Reporting, Technical Standards, Guidelines and Recommendations, and other resources.

Data Collection

Austria is illustrative of the kinds of improvements countries can achieve in supervisory reporting, with good planning and attention to the implementation challenges. The central bank, OeNB, led a multi-year project to revamp the data collection mechanism for the banking sector, integrating all main reporting requirements from within the OeNB and other authorities, including the Financial Market Authority. The main objectives were to integrate requirements and eliminate duplication and inconsistency of data across reports. To do so, granular data were needed. The project involved extensive consultations with the industry to define and standardize each granular data point collected. Large batches of granular data, after basic “transformation” of the raw business data, are “inputted” into a single database held at a company called AuRep (this can be considered a “push approach” with the use of a centralized structure for data storage). OeNB accesses the data from AuRep, after it is “transformed” again according to rules defined by OeNB in consultation with the banks. Despite the initial investment banks had to make for granular data reporting to become feasible and to set up AuRep, the use of a common reporting platform means that banks may be saving on reporting costs over the years. Very importantly, because of the granularity of the data sitting at AuRep, OeNB can change reporting requirements (the second level of “transformation” mentioned above) with virtually no cost to banks.

Machine learning Suptech tool at National Commission of the Retirement Savings System (Consar) of Mexico

Mexico’s National Commission of the Retirement Savings System (Consar) implemented a set of measures to produce high quality granular data reporting and invested in a machine learning tool as a substitute for manual data crunching.

The tool allows Consar to analyze granular transaction data and to spot, essentially in real time, detrimental customer interactions with private pension fund administrators, including fraudulent, abusive, and anticompetitive behaviors by these administrators and their agents. Customer interactions include account openings (for new customers), account closures, requests to switch to different institutions, withdrawals, and deposits

Consar decided to revamp the entire data collection system and introduce a data-driven supervisory process. To do so, it first mandated private pension fund administrators to fully digitize client-facing processes so it could generate analyzable digital data from each client interaction. The data are stored in a central database at Procesar, a third-party company owned by the private pension fund administrators. Procesar conducts reporting to Consar almost in real time.

Preliminary steps:

Consar took several preliminary steps to implement the tool:

- Issued a 2014 regulation to introduce digitized procedures on electronic devices and prohibiting paper-based procedures for customer interactions.

- Standardized data terms and formats for customer interactions, including minimum data requirements, geolocation data, and time stamps.

- Built a detailed agent database at Procesar. The agent database includes data on each agent, such as personal data, fingerprints, address, phone number, photo, age, etc.

- In 2015 Consar standardized the manner in which account switching could be completed (e.g. digital form, voice recording of customer acknowledgement, minimum disclosures by agents).

Technical methodology and data ecosystem:

- Although the private pension fund administrators own Procesar, the data it stores and processes are, by law, Consar’s property. Data are transferred to Consar approximately every two hours.

- The data feed a risk dashboard built and used by the data intelligence team, which shows, among other details, a map of transactions occurring across the country almost in real time. The team built risk indicators and thresholds that trigger alerts to the supervision teams for follow-up. Each transaction can be “zoomed in” on to show every detail about it (everything recorded in the client interaction digital forms). Each transaction provides access to full information about the agent conducting the transaction. Agent Profile reports are built with data retrieved from the agent database in combination with the transaction database. Each agent is risk-scored according to a color-coded methodology developed by the data intelligence team. All risk score details can be zoomed in on.

- Initially the agent risk score, risk dashboard, heatmaps, and alerts used relatively manual background procedures such as data downloads and rules (e.g., alerts) control. Visualization was performed using Microsoft Excel.

- Given the difficulty of processing and analyzing a large volume of data (millions of transactions daily), Consar decided to invest in a data analytics tool. It engaged a data analytics company to automate the risk monitoring and warning system via a machine learning application.

- Using real data provided by Consar as well as previous risk assessments, the company employed a deep learning application to identify patterns that could point to misconduct at the institution or agent level. Since the data used to train the application were real data, the accuracy of the machine-generated alerts and scoring could be confirmed through human-based past scoring and assessment.

Staff, expertise, and other requirements

The data intelligence team is comprised of five employees with expertise in data analytics and statistics; one was reassigned from another unit and the others were new external hires. These employees built the first Excel-based risk dashboard and engaged with the vendor, IDmission, to develop the machine learning tool. They are currently responsible for managing the data collection process, maintaining the tool, engaging with the vendor (as needed), and interpreting tool results—the basis for internal reporting to supervision teams.

In terms of data storage, Consar did not need to invest in local infrastructure since the solution uses a cloud provider (AWS) for data storage and processing. The cloud architecture is highly scalable and comparatively less expensive than building similar capabilities in-house.

Benefits and impact

- More efficient use of staff time. The time freed up was allocated to less mechanical and more analytical tasks, such as interpreting the results of the machine learning tool to determine appropriate engagement with supervisory teams for further investigation.

- Improved ability to identify risks and accordingly strengthen regulation. Another benefit was how, over time, the algorithms started to identify new types of risky behavior previously not identified by the original manual analysis system. For example, the practice of agents enlisting third parties (e.g., friends, subcontractors) to conduct a large number of transactions (to generate fees) could easily be identified—almost in real time. Identification of the practice led to a further change in the regulation that required all customer interactions to record agent and customer biometrics at the time of transaction.

- Better monitoring of anticompetitive behavior. The machine learning application was able to create a new method to identify potential anticompetitive behavior such as agreements not to “steal” each other’s clients. The algorithms specifically detected a suspicious absence of account switching between a certain group of institutions—an indication of potential collusion. The findings triggered further investigation and, in coordination with the competition commission, resulted in the largest-ever fine imposed on financial institutions in Mexico.

- Reduction in incidences of fraud. The changes noted above have allowed Consar not only to identify and act upon instances of suspected fraud, but to substantially reduce the amount of fraud and transactions with negative consumer outcomes.

- More effective prosecution of fraudsters. Another result is the referral of agents to the public prosecutor based on fraudulent behavior the machine learning tool has spotted. For example, the tool highlighted transaction patterns which raised the suspicion that transaction points, such as commercial establishments where customers make withdrawals and deposits, were requiring customers to make a purchase as a condition to conducting a financial transaction in their pension account. Another case that showed evidence of fraudulent account switching also resulted in hundreds of agents being permanently banned from exercising any professional activity within the pension system.

Data Analytics

European Central Bank (ECB) has employed (and is developing) several suptech tools and systems to make supervision more effective and more efficient. Examples include the following:

Heimdall is a custom tool for fit and proper assessments. Heimdall streamlines the assessment process by automatically reading fit and proper questionnaires filled in by supervised institutions and flagging issues based on their content. The tool makes use of optical character recognition, automatic translation and data analytics to reduce the manual workload and the possibility of human error.

Agora has digitized prudential analytics. The system gathers all prudentially relevant information in one place and technically integrates different datasets, creating a one-stop shop for prudential analytics.

Navi, short for “Network Analytics and Visualisation”, supports the analysis of complex data networks using graph analytics and an intuitive visualisation toolbox. It combines data from numerous sources to provide supervisors with a comprehensive overview of bank owners and interdependencies. Navi is an especially useful tool in the current context of increasing interconnectedness within the financial sector.

Organization and Capacity for Data

In 2017, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) created a “Data Analytics Group”, comprised of three units:

Data Governance & Architecture Office (“DGA”) formulates data management policies, manages data collection and quality, maintains MAS’ data catalogue, and publish MAS’ official statistics.

Specialist Analytics & Visualisation Office (“SAV”) conducts data analyses in partnership with MAS departments, helps departments improve their data capabilities through reusable tools and code libraries, and partners with MAS Academy to deliver data analytics training programs. Together with MAS’ IT Department, the team designs and implements the technical infrastructure needed to support data analytics work in MAS.

Supervisory Technology Office (“SupTech”) conducts data analyses on supervisory and financial sector data in partnership with MAS departments. It works with the Fintech and Innovation Group to promote data analytics capabilities within the financial industry and foster innovations to make regulatory compliance more efficient and effective.

South Africa Pilot on Customer Outcomes-Based Approach to Consumer Protection

The Customer Outcomes-Based Approach is an approach based on intermediate outcomes—translated into business practices, policies and regulations, and design—and accompanied by metrics that track high-level outcomes. The approach was developed by CGAP based on initial hypotheses about measures and metrics developed through input from a diverse group of private- and public-sector subject matter experts across jurisdictions. The list of indicators included 77 qualitative indicators deemed attestations or process statements and 79 quantitative indicators.

South Africa piloted the approach to test the validity and feasibility of indicators and financial service providers’ (FSPs) ability to gather required data. Partners included five FSPs (insurers and full-service retail banks), the market conduct authority (especially regulatory and supervisory staff), other experts (research experts on data and customer experience).

There were 20 indicators prioritized in the South Africa context selected based on the insights they provided. The 20 indicators were organized into five objectives of a recommended FSP strategy for measuring good customer outcomes. Indicators measuring Suitability, Choice, Fairness and Respect and Voice contribute to “meeting the customer’s purpose”. Though they are measured by different functional areas, they are linked and interpreted holistically to convey a customer-impact story.

| Objectives | Indicators |

|---|---|

| Objective I: Understanding customer segments and involvement: snapshot overview of the customer landscape within the FSP allows for context to guide interpretation of subsequent indicators. | Suitability

|

| Objective II: Optimizing product delivery and longevity: customers will retain and use products over time if the products—and the way they are sold—are suitable based on their needs. | Suitability

|

| Objective III: Minimizing erosion of income and benefits: customers expect products to work as intended and to derive their benefits, whilst being protected from loss of funds. | Fairness and respect

|

| Objective IV: Lowering cost to serve without sacrificing service: customers are guided to use lower-cost channels offered with a level of care and service as equally favorable as that for other channels. | Choice

Fairness and respect

|

| Objective V: Listening and responding to customers: when customers need to raise questions, communicate service failures or leave, the FSP should have the operational ability and intent to help. | Choice

Voice

|

Implementation of Supervision Approach

Onsite Inspections

Onsite inspections enable supervisors to access DFS provider facilities, run audits and tests on their information systems, interview staff and customers, observe staff as they conduct activities, and use other supervisory techniques to arrive at a fair assessment of the level and direction of risks DFS providers face.

This section highlights five steps to help supervisors optimize onsite inspections.

Step 1. Prepare as much as possible offsite

During offsite preparation, the supervisory team needs to identify the most concerning issues at the highest level of specificity possible. All team members should be aware of what they need to acquire from the DFS provider and what they must produce and achieve during interactions with the DFS provider. The team should also consider how best to use technology for effective remote and in-person provider interactions. With the right planning and mindset, many of the activities and analyses previously performed onsite can and should be done remotely (e.g., use APIs to connect to the DFS provider’s systems). With APIs, the team can even partially or entirely conduct system audits.

Step 2. Collect sufficient information prior to inspection

Supervisory teams should exhaust efforts to remotely collect information prior to moving on with interactions with the DFS provider unless there is a specific reason for not doing so (e.g., probing into a certain issue needs to remain confidential until arrival onsite). In many countries, the initial request is the same document where the supervisor announces inspection date(s). It is important to remain flexible in terms of dates since preparations may take longer than expected. Rigidity on start date and number of information requests sent is not uncommon among supervisors but may reduces efficiency.

Step 3. Develop tailored questions for inspection meetings and interviews

Inspection meetings and interviews should not primarily be seen as fact-finding events but as techniques that allow supervisors to confirm, expand upon, and find causes for issues already identified during offsite preparations. For instance, rather than conducting interviews and meetings to review “yes” or “no” questions from a standard checklist, effective offsite preparation equips supervisors to ask more substantial questions about “why,” “how,” and “who.”

Step 4. Produce inspection documents based on internal guidance

Supervisors should be given internal guidance and templates for preparing inspection documents. The same applies to the inspection report, which should describe the inspection’s objective, scope, techniques used, main findings, and recommendations or corrective measures. It is also good practice to conduct internal meetings with superiors and colleagues to discuss weaknesses and other significant findings, especially those that would trigger enforcement procedures or corrective measures that could significantly impact the DFS provider. Prior to finalizing the report the supervisor should conduct a dialogue with the DFS provider to clarify findings and potential recommendations.

Step 5. Corrective measures, enforcement, and follow-up

The most common outcome is an action plan that details the problem, the corrective measures to be implemented, and their respective timelines. Supervisory teams should follow up according to the specific timeline of each measure rather than wait for the next planned inspection. If weaknesses are serious or recurrent or if previous corrective measures have not been implemented, formal enforcement measures may be considered, such as fines, withholding approval of new products or acquisitions, suspending operations, imposing the requirement to hold additional capital, replacing, or restricting executives, limiting dividend payments, or referral to a criminal authority. Supervisory authorities may also require special external auditing or impose additional reporting obligations.

Implementation of Supervision Approach

Resolution of DFS Providers

A well-designed wind-down regime should seek to minimize value destruction by mitigating the financial, economic, and social costs associated. The purpose of a resolution regime for financial institutions is: (i) to maintain financial stability and (ii) to ensure continuity of critical functions to the financial sector and the economy, such as payments, clearing, and settlement services.

The orderly wind down of a DFS provider should be conceived as one component of the broader financial institutional framework. Without proper regulation and supervision, authorities may not have the necessary mechanisms to monitor the eventual deterioration in the situation of a DFS provider and attempt an orderly wind down. In the absence of a specific resolution regime, authorities may have no option but to let DFS providers fall under the standard corporate insolvency regime. These regimes do not consider particulars of financial service providers, in particular entities that collect repayable funds from the public.

Overall, the resolution regime should enable financial authorities to deal with DFS provider failures. The regime would aim to minimize the failure’s negative impacts on customers, the real economy, financial stability, and taxpayers. It would include a resolution plan) that equips a resolution authority with unequivocal powers and a range of tools to deal with DFS providers that are no longer viable, or likely to be no longer viable, and whose failure may significantly impact policy goals—including, for instance, power and policies to transfer part or the total of a provider’s operations to another provider in order to preserve critical functions and minimize disruptions.

The failure of a large DFS provider (even one that does not take funds from the public) may not only impact customers but also other DFS providers and the reputation of the supervisory authority. A specific resolution regime would allow authorities to take the following actions, among others:

- Remove and replace senior management and directors of the DFS provider

- Appoint an administrator to take control of and manage the DFS provider

- Operate and resolve the DFS provider, including powers to terminate contracts, continue or assign contracts, purchase or sell assets, write down debt, and take any other action necessary to restructure or wind down operations

- Transfer or sell assets and liabilities, legal rights, and obligations to a solvent third party

- Transfer certain functions and viable operations of the failing DFS provider to another institution

- Effect the closure and orderly wind down of the whole or part of the DFS provider, with prompt access to customer accounts or funds

Insolvency of EMIs in the UK

Authorized Payment Institutions (APIs) and EMIs in the UK are required to protect customer money through fund safeguarding. They either keep customer money separate from their own money or protect it with insurance or comparable guarantee. The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) clarifies that fund safeguarding may produce worse consumer outcomes than the past performance of the UK’s deposit insurance scheme. It may take longer for customers to get their funds back, or there might be no funds left after the administrator or liquidator of the insolvent EMI deducts its costs from the EMI assets. Customers may not get their money back. Also, the FCA warns customers that if the EMI or API is not safeguarding customer funds properly, they could get nothing back at all. Moreover, customers may need to contact the administrator or liquidator to get their money back. These situations may not be appropriate where e-money is used by a large portion of the population, including vulnerable populations.

In fact, six APIs and EMIs have entered insolvency since 2018 in the UK but only one has returned customer funds. Supercapital Ltd. was one of the firms that became insolvent. In September 2019, the firm ceased to provide any regulated business and the administrators (i.e., insolvency practitioners) were appointed to take control of the firm, including managing customer claims against the firm. FCA advised that customers who believe that they are owed money by Supercapital should contact the administrators.

According to its administrators, the firm is short of approximately £585,000 owed to customers. The prospect of recovering these sums is uncertain The shortfall would probably have been detected if the firm had effective reconciliation procedures described in this section and related resources.

Due the shortcomings of applying the general insolvency regime to financial institutions, the UK recently issued the Payment and Electronic Money Institution Insolvency Regulations, which introduce a special administration regime for insolvent payment institutions and EMIs, with the objective of ensuring that customers are reimbursed without any delay and minimizing the shortfalls in meeting the amounts owed to customers.

Risks with Emerging DFS business models

Consumers participating in peer-to-peer lending (P2PL) platforms as lenders/investors may risk losing their committed loan principals, or repayments owed to them, that are being held or administered by a platform operator that goes insolvent or fails. Borrowers can also face risks of losing funds under such circumstances. For example, when consulting on proposed regulatory reforms for P2PL in the United Kingdom, the FCA said it considered P2PL platform operators to present a high risk of consumer harm, given they may hold or control client funds before lending to borrowers. Likewise, a borrower may miss out on receiving funds intended for them from lenders/investors as a result of the operator’s insolvency.

The EBA has pointed out the risk of lender/investor funds not being transferred to the intended borrower if the platform is not required to hold appropriate regulatory authorizations and have in place adequate arrangements to safeguard such funds. Depending on the legal relationships between the parties, borrowers may also suffer losses when the repayment of loans they make through the platform fail to reach lenders/investors. An investor can suffer considerable harm if a P2PL platform ceases to provide management and administration services. In practical terms, this can mean an individual lender/investor not receiving some or all repayments for the loans that they made or invested in through the platform, unless they retrieve payments directly from borrowers themselves.

An investment-based crowdfunding platform’s failure can similarly leave investors without services essential to realizing the full value of their investment. The extent and nature of such risk depend on factors such as whether the platform holds client money, undertakes payment services (for example, channeling payments from issuers to investors), represents investors through a nominee structure, or runs a secondary market for issued securities. Loss of access to such services from the operator due to temporary or permanent platform failure can cause financial loss as well as operational detriment to investors.

Departures from a regular insolvency regime are only warranted in those cases where there is a public interest to do so. For certain firms, regular insolvency regimes may not be feasible due to their potential systemic impact over the financial sector and the economy. This may happen due to the size and systemic importance of the firm (that is, when they are “too-big-to-fail.” For example, large firms engaged in payment transactions or large EMIs) or to the simultaneous failure of several players on the same market (that is, when there are “too-many-to-fail”). This assessment must be done at all relevant market levels (local, regional, and national). For example, in remote communities, often underserved by banks, closing the only financial institution that is present could have a significant impact on the local economy despite not being relevant at the country level.

Implementation of Supervision Approach

Overcoming Supervisory Capacity Challenges

Supervisory capacity includes all factors which ensure that supervisory functions and activities are carried out effectively and in a timely manner. Capacity includes the following:

- Adequate number of human resources with appropriate expertise and skills.

- Clear reporting structures with DFS providers.

- Governance of data quality (accuracy, timeliness, appropriateness).

- Availability and ability to use supervision technology.

- Coordination with other departments and other institutions.

- Effective internal communication channels (which align with pace of DFS risks).

Supervisory capacity is almost always limited, and more so in the context of a rapidly evolving DFS landscape. There is a need to assess baseline capacity and update that assessment at appropriate intervals.

Preliminary Supervisory Capacity Assessment

| Strengths | Improvement areas | Priority | Actions | Timeline | Budget / resource needs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human resources | ||||||

| Number | ||||||

| Skills | ||||||

| Expertise | ||||||

| Data | ||||||

Quality

| ||||||

| Data governance (e.g. security, anonymity, transmission) | ||||||

| Reporting systems | ||||||

| Supervision technology | ||||||

| Monitoring tools | ||||||

| Capacity (to use) | ||||||

| Data analytics | ||||||

| Data visualizations | ||||||

| Coordination | ||||||

With other departments

| ||||||

| With other institutions | ||||||

| Internal communication | ||||||

| Channels, formats and frequency | ||||||

| Emergency communication |

Learning Cultures and ‘Soft Skills’: Note that it may not always be necessary to increase staffing and implement new systems. There may be opportunities for learning and development and re-tooling systems particularly when certain DFS risks fade and new risks emerge.

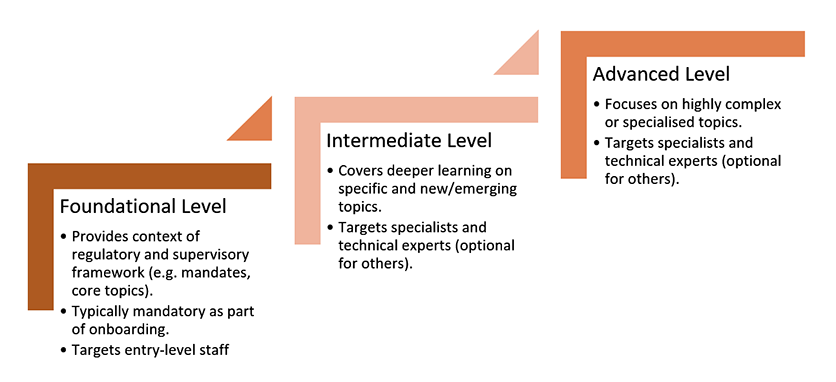

There is a range of training cultures in financial authorities – some preferring a push-based approach, while others relying more on a demand-based approach, or a mix of the two.

Supervisory Training Curve

In general, foundational and intermediate topics are typically push-based while more advanced topics are more demand-driven. A push-based approach typically involves pushing or prescribing courses to specific groups of staff members. On the other hand, a demand-based approach involves staff members themselves voluntarily and proactively identifying and requesting training based on their own developmental needs.

While a demand-based approach can address the issue of staff time scarcity, it requires a proactive and mature organisational learning culture to work. A mature learning culture would see even experienced staff undergoing refresher programmes on fundamental core supervisory topics on a regular basis while continuously expanding their knowledge and skills on emerging topics.

Importantly, supervisory staff may also benefit from ‘soft skills’ which foster personal and professional development. These may include interpersonal skills, communication skills, time management, problem-solving, conflict management, leadership, and collaboration/team work, among others.

Transition periods: There could be temporary arrangements for the internal organization for DFS supervision. For instance, in the initial stage of DFS supervision (e.g., in the year following the issuance of a new DFS regulation), a team inside a pre-existing department, such as banking supervision, may become responsible for the core functions of DFS supervision. The situation may persist until a team with the adequate skills and expertise is formed, a head of unit is appointed, and the organizational chart is changed. Regardless, it is important that DFS supervision receives the required level of attention and resources according to the growing importance and sophistication of the DFS markets in the country.

Budget allocations: Supervision capacity requires financial resources. Even when required improvements are minimal, there is a consistent need to maintain capacity and keep it aligned with market and institutional DFS risks. Internal budgets should be distributed in accordance with the distribution of supervisory functions and activities. When they are not, they must be negotiated. In all cases, there should be a clear mechanism for justifying resource needs and assigning responsibilities. For enhancements that represent projects (e.g. upgrading a reporting system and building internal and DFS provider capacity to report), there may be a need to tap into funding from external project sources (e.g. public sector development budgets, international financial institutions).